This isn’t the first time a virus caused social panic. The Spanish flu did too

The 1918 flu was one the worst pandemics in history, infecting one-third of the world’s population. How cities responded to the crisis in 1918 provides lessons on handling COVID-19 today.

There were warnings by politicians and doctors that the pandemic was coming. Mandatory quarantines followed, along with skepticism by a public that felt the threat was all hype.

Then, the deaths started.

This scenario is unfolding across Southern California, as the region bunkers down against coronavirus and reported cases continue to rise.

But the same sequence played out more than 100 years ago.

Archives at UCLA, the Huntington Library and the City of Los Angeles capture the little-remembered history of how Los Angeles and other cities across the Southland weathered the deadly 1918 Spanish flu, which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide and over 700,000 in the United States.

Through letters, newspaper clippings, city council minutes, diaries, and photos, these collections offer lessons from the past that historians say can teach people today about how to confront coronavirus.

“Until recently, a pandemic had been kind of abstract,” said Carla Bittel, a Loyola Marymount University history professor who has had her students use archival material to write projects about the Spanish flu. Some of the topics they chose — the efficiency of wearing masks, the pressure on men to suffer silently, the toll that caring for the sick took on healthcare workers — seem pulled from the debates over coronavirus today.

“Holding stationery in their hand, it was very poignant for them, in a way that just reading a book wouldn’t be,” she continued.

These archives aren’t readily accessible to nonacademics, and copyright restrictions limit their use. But their caretakers pop up every couple of years in the public sphere to calm collective nerves, much like Lucy Jones, the Caltech seismologist and longtime fixture on Southern California television and radio any time there’s an earthquake.

Interest “is in spurts” tied to whenever pandemics make global headlines, says Russell Johnson, curator for UCLA’s special collections for the sciences. “It’s understandable.”

Over the past eight years, he has compiled one of the few archives in the United States devoted to the Spanish flu, with special attention paid to correspondence between military members and their families. That focus is crucial to understanding how the Spanish flu spread across Southern California.

The first quarantines in the region were enacted in September 1918 at the Naval Reserve Station at Los Angeles Harbor and the U.S. Army Balloon School in Arcadia. The disease had struck the United States earlier in the spring, but a second, more-lethal strain swept across the country that fall, brought back home by soldiers who had fought abroad during World War I.

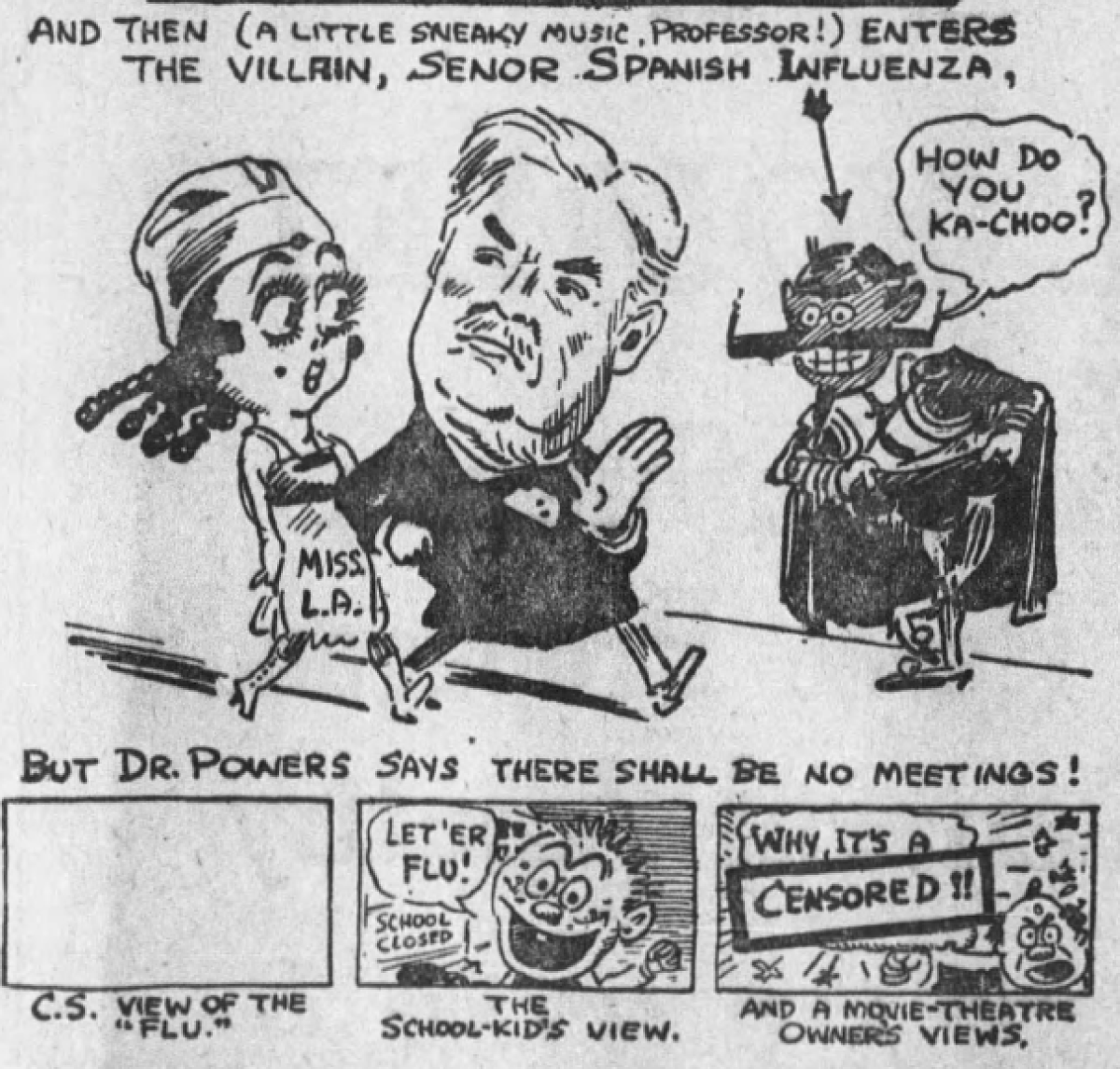

By Oct. 11, Los Angeles City Health Commissioner Luther M. Powers ordered the shutdown of schools and all public gatherings, including funerals, movie theaters and church services.

The ensuing chaos is documented in the telegrams and handwritten letters that Johnson has amassed. They’re held in three boxes and can only be viewed in the reading room near his offices at UCLA’s Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library.

He did show off parts of the collection for a UCLA exhibit in 2014, a time when swine flu was the contagion du jour. Most of it centered on a large scrapbook that tells the tale of Army cadet Alton Miller of Kingston, New York.

Bought from a private collector, it showed the arc of Miller’s military life: family pictures, a driver’s license, a draft notice. A succession of letters to his sister and father from training camp reveal the young man’s changing fate: Miller tells them that other soldiers have influenza, Miller admits he contracted it but is confident that doctors will cure it fast, a friend writes to tell Miller’s family that Alton is ill.

The exhibit ended with an Army telegram informing Miller’s family that he died.

“You could see a couple of people clutching themselves when they got to that part,” Johnson said.

Another item that Johnson says gets reactions: a telegram that Edward Rainey, secretary to San Francisco’s mayor, sent to Santa Barbara Mayor Harvey Neilson. Rainey pleads with Neilson to enact a mandatory mask ordinance “because I have seen the whole terrible effect of epidemic here … because masks have saved untold suffering and many deaths.”

“These archives show how almost commonplace [influenza ] became,” Johnson said. “Life had been disrupted, but life is going on.”

A similar assortment of Spanish flu ephemera is at the Huntington Library in San Marino and is spread out across multiple collections. There are pictures of swamped hospitals and tired nurses taken by Pasadena photographer Harold A. Parker, diaries by Red Cross volunteers, and the papers of the Los Angeles County Medical Assn., which feature internal reports and recollections.

“The lessons we learn about COVID-19 from looking at historical pandemics: Trust the medical professionals and public health experts, who will help you to avoid misinformation,” said Joel Klein, head of the Huntington’s science collections, one of the largest in North America. He also noted that the Huntington’s records show how “fearful people responded in unhelpful ways that were rooted in racism and xenophobia.”

One example: At the height of L.A.’s fight against the Spanish flu, over 100 white student nurses at Los Angeles County Hospital resigned because the Board of Supervisors had allowed African American women to work alongside them.

The biggest lesson Klein said people can take from then for now is “we will get through this best if we all work together.”

At the C. Erwin Piper Technical Center near downtown, Los Angeles city archivist Michael Holland tells L.A.’s 1918 flu story through stats and ordinances. One report titled “Classifications of Death” showed that between 1918 and 1919, 2,713 Angelenos died due to influenza — 26% of total deaths for those two years, with more than half of the deceased between 20 and 45.

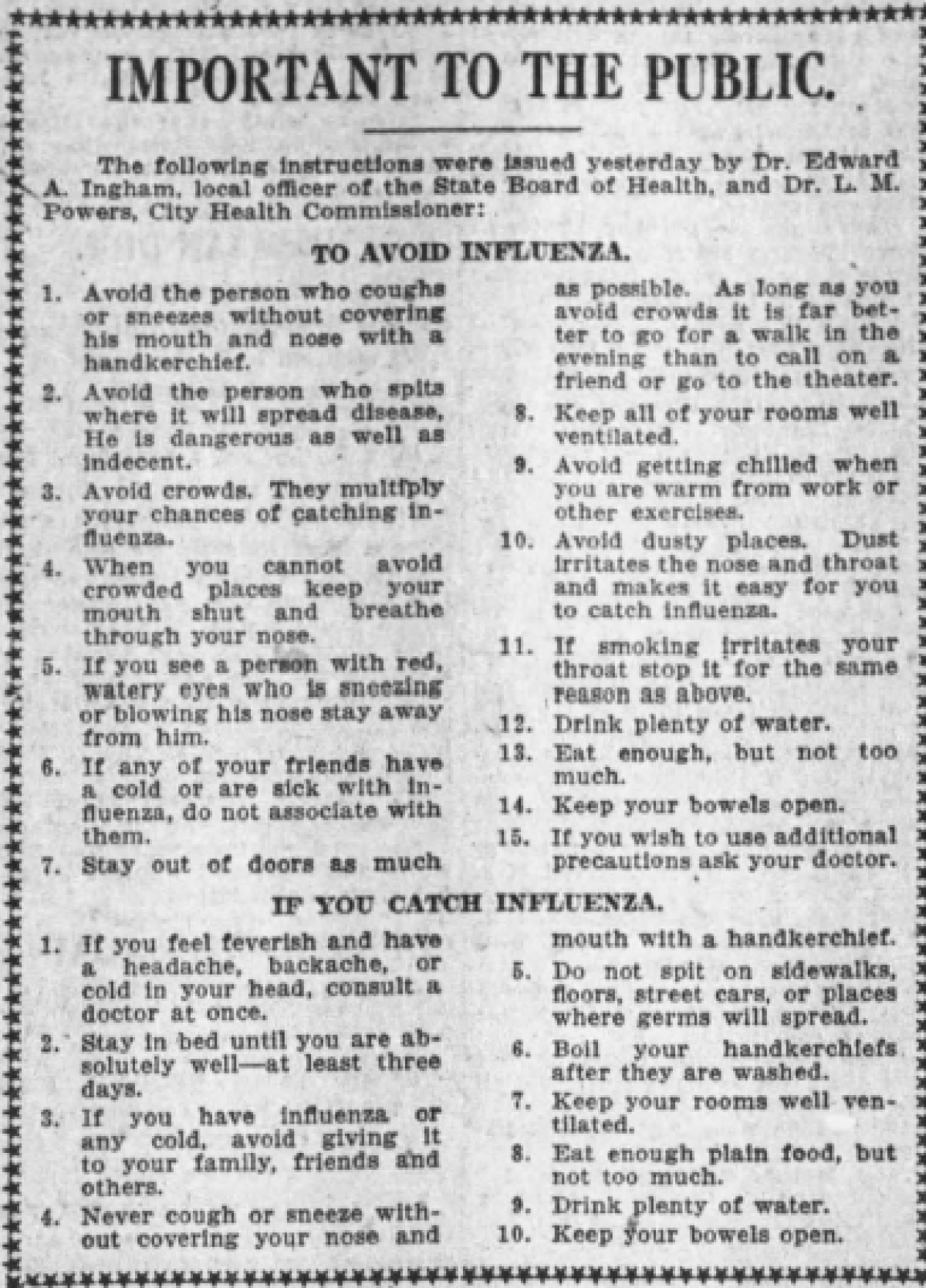

Holland credits Commissioner Powers’ quick quarantine with limiting the Spanish flu’s impact on Los Angeles compared with other cities — while L.A.’s death rate was 494 deaths per 100,000 people, San Francisco’s was 673 per 100,000. He urged the city’s daily newspapers to print bulletins that instructed those infected “to stay in bed … keep your rooms well-ventilated, eat enough plain food, but not too much” and “keep your bowels open.”

The commissioner’s stringent actions and words didn’t win him many fans.

Christian Scientists successfully sued for the right to hold meetings; movie theater owners complained their industry was unfairly targeted and urged the city council to close all businesses. In a foreshadowing of today’s battles against homeless shelters in neighborhoods, Holland mentioned a petition that residents of Elysian Park submitted to the City Council asking that an emergency hospital not be built there.

“Powers basically said, ‘The hell with you, we’re doing it for the greater good,’ and got it built” Holland said.

While praising how Los Angeles officials reacted to the Spanish flu, he also noted that their modern-day peers “are much more coordinated than we were a century ago. This is one of those instances that they really have learned from the past.

“It really is that old saying that we historians dearly love because it justifies our existence,” he said. “Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.