Is California headed back into drought, or did we never really leave one?

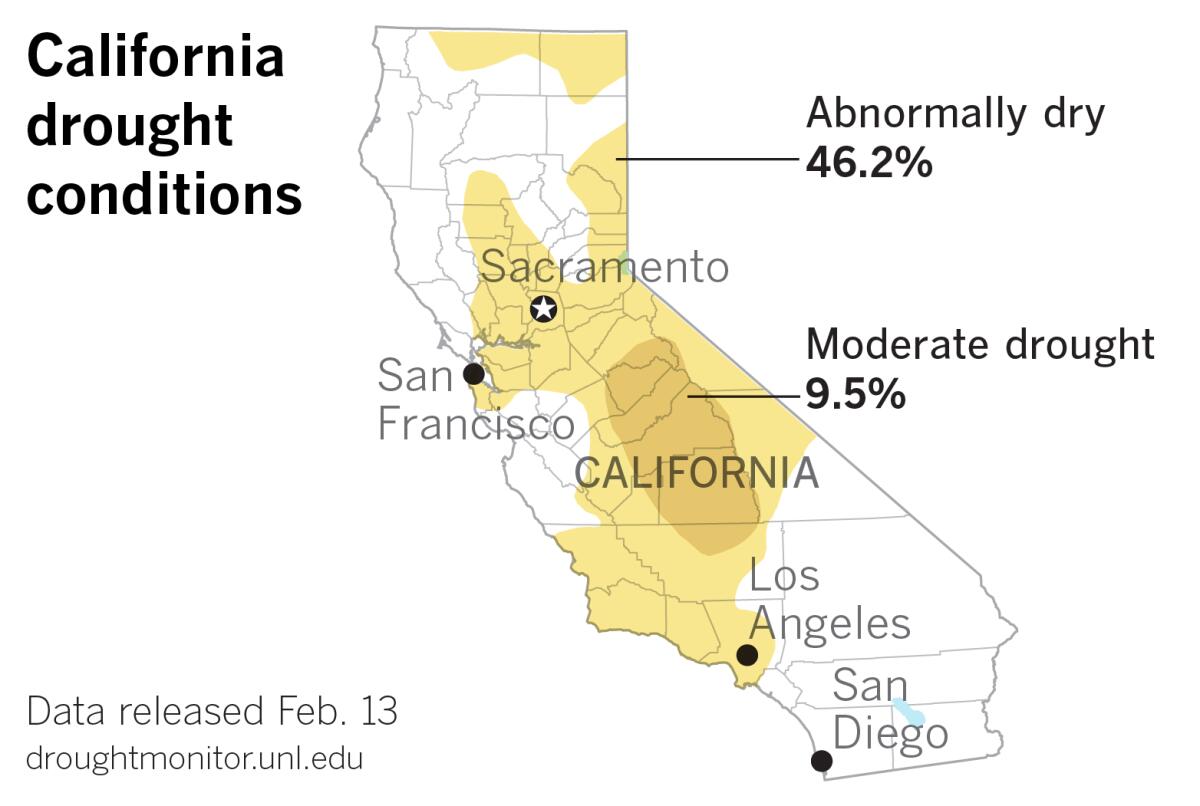

The most recent U.S. Drought Monitor, issued on Thursday, shows an oval-shaped patch of Central California slipping back into moderate drought. This is after a couple months where the Drought Monitor showed the state to be almost drought-free.

The 2018-19 water year that came to a close last June was good — above average in many places in the state — but not great. The 2019-20 water year got off to a fast start with a couple of potent storms, and Southern California was above seasonal norms even as Northern California lagged. Then January and February — two of the state’s wettest months — turned bone dry. And February looks unlikely to overcome its arid habits before the month ends, even though the calendar has given it an extra day this year in which to try.

A persistent ridge of high pressure has taken up residence in the eastern Pacific, and it shows no sign of budging. It is diverting storms into the Pacific Northwest region, which means more dry weather for California.

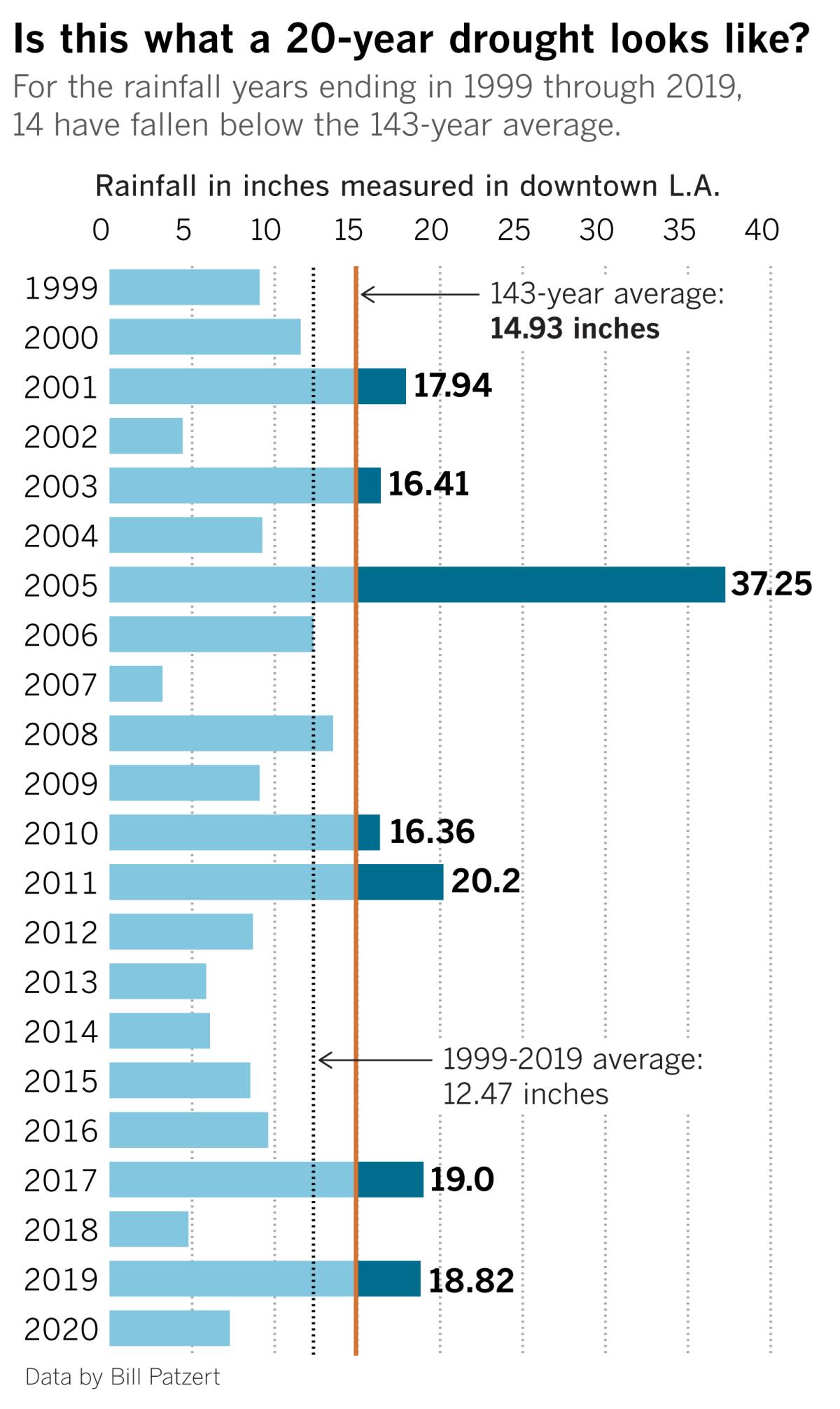

But did the drought in California ever really end? Climatologist and weather expert Bill Patzert thinks Southern California continues to be mired in a two-decade drought, and he uses rainfall figures for downtown Los Angeles to illustrate his point.

Over a period of 143 years, the average annual rainfall recorded in downtown Los Angeles has been 14.93 inches. Rainfall figures for downtown Los Angeles from 1999 to 2019 show many more disappointingly dry years than robustly wet ones.

During the 21 years ending with the 2019 season, 14 years have been below average, and only seven have been above, according to Patzert, who until recently was with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In fact, three of the driest years since 1878 occurred during this period: 2002, 2007 and 2018. The period from 2012 to 2016 accounted for the five driest consecutive years on record, when the average rainfall each year was only 7.74 inches, or 50% of normal.

Between 1999 and 2019, downtown Los Angeles was a total of almost 52 inches below average, Patzert points out. “That’s like losing 3½ average years of rainfall over the last 21 years.”

The lower rainfall brought the average for those years down to 12.47 inches per year — 2.47 inches short of normal each year, on average. “That’s mucho groundwater, irrigation for crops, lots of dead lawns and mass mortality in the great forests of California,” said Patzert.

“This drought did not simply come and go every other year, it has continued to deepen for two decades,” Patzert explained. “And the impacts have been long-lasting for urban dwellers, farmers, water managers and especially firefighters.”

The effects of persistent drought last a long time. For example, Lake Mead, a key reservoir formed by the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, supplies water to millions of people in Arizona, California and Nevada, including Los Angeles. In 1999, its level was 1,212 feet above sea level. Now it’s at 1,094 feet — 118 feet lower — which represents a 50% drop in the volume of the lake. It will take decades for the reservoir to recover, Patzert warns.

“That’s ominous because the population served by water from the Colorado River has exploded since the 1950s,” said Patzert. “Lake Mead is our drought monitor for the American Southwest.”

Patzert emphasizes that although one or two dry years can be punishing, a slowly building, large-scale drought is much more damaging. Long, major droughts are not zero or 50% below-normal rain. Droughts are when you drop from an average of 14.93 inches of rain per year to 12.47 inches — a subtle 16% decrease in average rain for 21 years, he explained. The two-decade drop in the level of Lake Mead is the result.

“History and science show us that droughts are large, long-lasting, and they wax and wane,” said Patzert. “This is especially true in the American West. The great Dust Bowl started in 1930 and lasted for almost a decade. California experienced on-again, off-again drought from the mid-1940s through the late 1970s. During these prolonged dry spells, a single wet year or two can provide temporary relief but will not break a multiyear drought.

“Droughts build incrementally, and recovery happens in slow motion, not with one wet year,” he said. “Droughts fool you. You think you’re out, and they pull you back in.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.