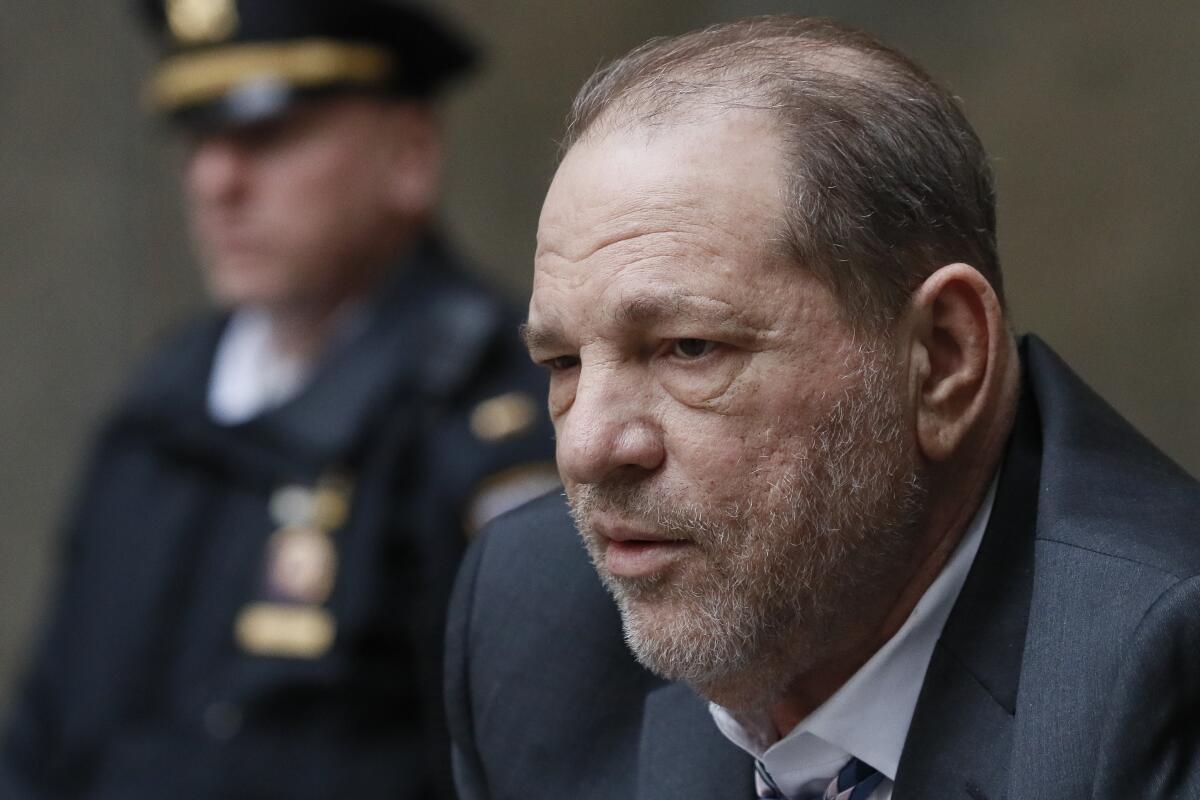

As Harvey Weinstein’s fate heads to jurors, who will they believe?

NEW YORK — One by one, the women shook, cried, stammered and struggled to recount the horrors they said Harvey Weinstein inflicted upon them.

Annabella Sciorra wept as she told jurors the mogul had barged through her front door and forced her onto a bed. Mimi Haley hung her head as she recalled a night when she didn’t want to have sex with Weinstein, but simply “laid there” out of a fear that she couldn’t escape a producer who physically dwarfed and overpowered her.

Jessica Mann, exhausted by her marathon testimony about a tumultuous and complex relationship with Weinstein, had to be helped from the stand as she sobbed between panicked breaths.

During three weeks of testimony, the former Hollywood titan sat in relative silence. He scribbled on a notepad or stared at the jury as his attorneys scrutinized each accuser’s motives and behavior, confronting them with cordial emails they wrote to the mogul while trying to recast each woman’s account as nothing more than an edited version of a consensual affair.

When a jury of seven men and five women convene next week to decide Weinstein’s fate, experts say they will have to determine which framing of the case they will follow: The tearful words the accusers delivered, the praise-heavy missives they later sent to Weinstein calling him a “genius” or seeking his help finding work — or the prosecution’s assertion that both conditions can exist at the same time.

In her closing arguments Friday, prosecutor Joan Illuzzi-Orbon told the jury that Weinstein had underestimated his accusers.

“He made sure he had contact with the people he was worried about as a little check to make sure that one day, they wouldn’t walk out from the shadows and call him exactly what he was: an abusive rapist,” she said. “He was wrong.”

The prosecution’s final argument was designed to undercut the seeds of doubt painstakingly planted by Weinstein’s attorneys. They have repeatedly seized on the fact that Haley and Mann kept in contact with Weinstein after their alleged assaults, while also insisting the women were not victims, but opportunists seeking connections and acting roles.

Illuzzi-Orbon made the point Friday that rape can occur within otherwise consensual and committed relationships. Even still, the accusers’ continued communication with Weinstein — coupled with gaps in their testimony about the dates and times of the attacks — could sway the jury toward an acquittal, legal experts say.

“I think the most important part is the emails ... that’s tough to refute at that moment. They were saying something other than they were saying now,” said Dmitriy Shakhnevich, a criminal defense attorney who now teaches at the John Jay School of Criminal Justice in Manhattan.

To overcome that correspondence, Shakhnevich said prosecutors will have to hope jurors focus on the testimony of forensic psychologist Barbara Ziv, who attempted to knock down so-called rape myths — including the notions that victims always fight back against their rapists, or that the truthfulness of a rape allegation can be evaluated by how an accuser behaves afterward.

Mann’s consensual sexual interactions with Weinstein after the alleged attack may be a sticking point for one or more jurors, said Wendy Murphy, a professor of sexual violence law at New England Law in Boston and a former sex crimes prosecutor.

Even when the laws around rape are clear and the evidence is powerful, she said, there may be jurors who will “have a tough time valuing what happened to that woman’s body as a serious enough crime to warrant a criminal conviction” because of a “historic disrespect for women in this country, and rape victims in particular.”

Illuzzi-Orbon said that Weinstein kept in contact with his victims in order to control and isolate them. The Miramax co-founder dangled roles in front of his accusers, she said, some of whom were trying to establish their acting careers.

The prosecution outlined the ways in which the accounts of abuse were strikingly similar: Interactions with Weinstein that fluctuated between validating and humiliating. The producer’s rapid changes in demeanor, which could sometimes swing from friendly to menacing in a matter of moments. And efforts to trick and trap the accusers in ways they said appeared premeditated.

“When you have to trick somebody to be in your control,” Illuzzi-Orbon said, “then you know that you don’t have consent.”

In her closing arguments Thursday, lead defense attorney Donna Rotunno implored the jury to focus on the evidence presented at trial rather than the maelstrom of negative press Weinstein has received between the start of the #MeToo movement and his trial.

In all, more than 90 women have come forward with sexual misconduct allegations against Weinstein.

“You may have had a gut feeling that Harvey Weinstein was guilty,” Rotunno said. “Throw that gut feeling right out the window.”

Weinstein’s jury was chosen specifically for their professed ability to ignore media coverage and decide the case based only on evidence heard in court. But that doesn’t mean jurors won’t be biased against Weinstein when they make their decision.

Take Bill Cosby’s rape case, Murphy said. By her evaluation, the comedian had a good chance of winning his mistrial under Pennsylvania law.

“Had he been a run-of-the-mill guy, if he hadn’t been the subject of so many news stories, he would have walked,” Murphy said.

Rotunno also argued that Weinstein’s accusers made the choice to go to his apartment or his hotel room, that they made the choice to engage in sex with him, and that they should take responsibility for those choices.

Illuzzi-Orbon rebuffed those claims.

“If you take the short way home and walk through a dark park and get robbed, nobody’s going to say, ‘You shouldn’t have been walking through the dark park,’” Illuzzi-Orbon said.

Weinstein, 67, faces five felony charges in the New York trial, including rape, criminal sexual assault and predatory sexual assault. He faces a minimum of 25 years in prison and could be locked away for the rest of his life if convicted on the last charge.

The charges stem from accusations by Haley, a former employee of Weinstein’s production company who alleges he forcibly performed oral sex on her in 2006, and Mann, a former aspiring actress who testified that the producer raped her in a New York hotel room in 2013.

To earn a conviction on the predatory sexual assault charge, prosecutors must convince jurors that Weinstein assaulted Haley or Mann, as well as Sciorra, the “Sopranos” actress.

The nature of the predatory sexual assault statute could also work against the prosecution, Shakhnevich said. To convict on either of those two counts, jurors must believe Weinstein assaulted Sciorra and Haley or Sciorra and Mann. While Shakhnevich described Sciorra as the prosecution’s strongest witness because she cut contact with Weinstein after the date of the alleged assault, the jury cannot legally convict on her accusation alone.

Three other women testified that Weinstein assaulted them. Those alleged crimes were either too old to prosecute or happened outside the jurisdiction of the Manhattan district attorney’s office, but the allegations of one of the women, Lauren Young, about an assault that she said occurred in a Beverly Hills hotel, led prosecutors to file charges against Weinstein in Southern California.

Weinstein has denied any wrongdoing and pleaded not guilty to all charges. Jury deliberations are expected to begin Tuesday.

In a direct rebuke of the defense’s argument that Weinstein’s accusers sought attention through their involvement in the sensational case, Illuzzi-Orbon said they were instead “compelled by their own morality.”

“Would they put themselves through the stress? Did it look like they were having fun up there? Did it look like that was a party, was that a premiere?” Illuzzi-Orbon said. “Or did it look like that was horrible and grueling?”

Newberry reported from New York. Queally reported from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.