Column: About to become teachers, they’re worried about affording the rent

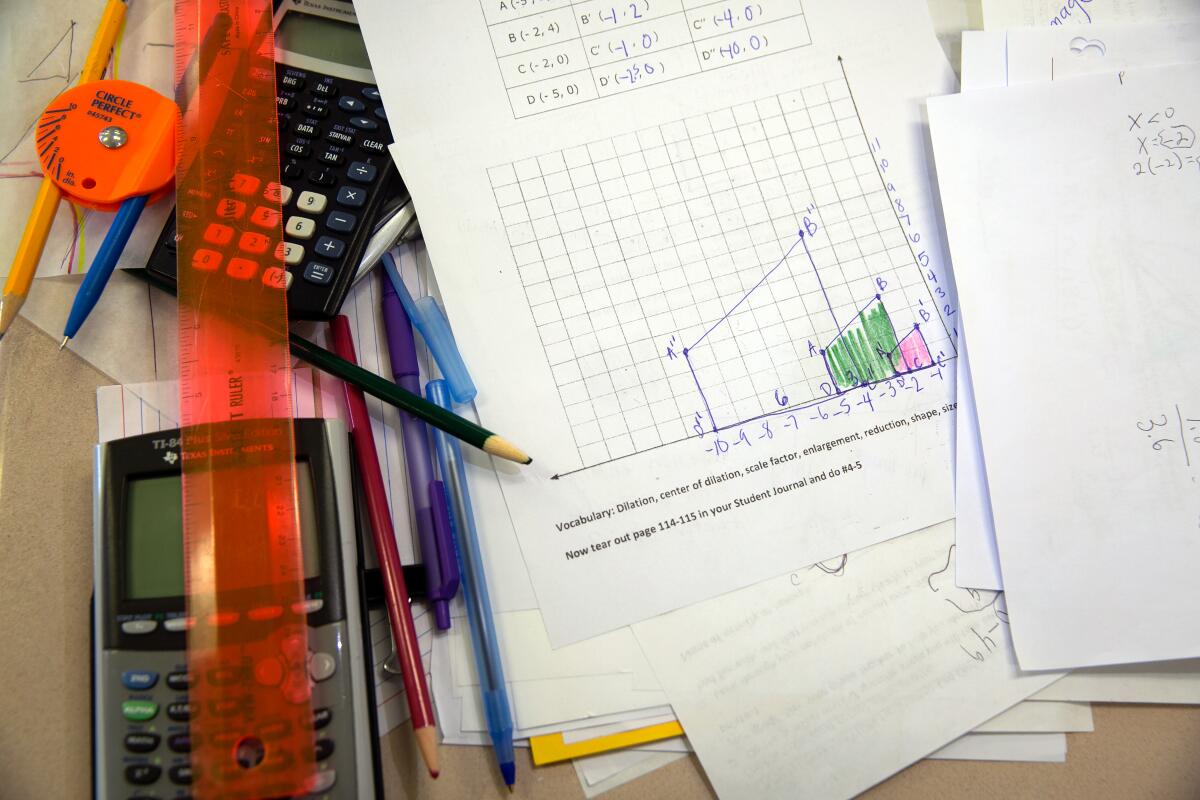

“So what we’re going to do now is label our triangles,” student teacher Keiri Ramirez told her class at Northridge Academy High School. “A prime, B prime and C prime.”

Ramirez, inspired by her middle-school teacher in Huntington Park, is about to graduate from Cal State Northridge and become a teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District, where the starting salary is about $53,000. She’s a natural in class, with a big easy smile and lots of encouraging words as she leads 23 students through a drill on triangle dilation.

But Ramirez, 23, knows what lies ahead in a region where housing costs have soared while wages for teachers have been pretty flat. When she got her math degree a year ago before starting on a teaching track, she thought about angling for a job at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and she thought about moving to a less-expensive area.

But L.A. is home and she loves teaching, so she’s going to make it work. At the moment she shares a two-bedroom apartment with three roommates, two of whom are going into teaching along with her.

“Three out of the four of us graduate in May and the plan is to live together for another year or two, until we get settled,” she said, and then they’ll see if they can afford places of their own.

It’s the California paradox. There’s so much wealth and demand for housing, prices have gone way up and put even more financial stress on the very people who help power the economic engine.

That strong economy is luring students out of teaching and into more lucrative fields, said CSUN’s education department dean, Shari Tarver-Behring, who has seen a steep drop in the number of teacher candidates.

“Nationally and statewide there’s been a decline,” Tarver-Behring said. “They’re making such an important contribution to our society, and yet we do not value them in terms of how they’re paid.”

They’re making such an important contribution to our society, and yet we do not value them in terms of how they’re paid.

— CSUN education department dean Shari Tarver-Behring

As I dropped in on education classes at CSUN with Tarver-Behring, she made a point of thanking students for committing to a noble profession. Some of them, she pointed out, are mid-career people who decided that living right might be more satisfying than living well.

Lynne Johnson told me she left the insurance industry after 25 years because it was little more than a job. Teaching, she said, is a commitment to social justice.

“You have 36 kids in class and that’s a lot of influence and you can make their lives better,” Johnson said. As a student teacher, she’s already experienced the thrill of having students call her their favorite. “I had a student come in and spend lunchtime with me today.”

Gregory Winley said it’s not all about money, but about doing what you love to do, and he wants to be an English teacher.

Chase Stauffer, another English teacher in the making, said no one should be surprised that teaching is not well-compensated.

“It’s by design,” he said. “Neoliberalism is the siphoning of funds from public programs into private funds. Los Angeles has more millionaires than any other city and yet we’re constantly told there’s no money in education. … I wanted to do something that’s public, to be a part of public education, to be in a union because I believe in that. We’re fractured and atomized as a society, and the only way things will get better is if good, smart people … decide it’s time to seek meaning in life beyond self-enrichment.”

I told him I admired his commitment but wondered how he intends to pay his bills. Turns out he has a good sense of humor along with all that passion.

“I have no idea,” he said.

Shireen Pavri, dean of the education department at Cal State Long Beach, said many of her grads have traditionally gone straight to jobs with Long Beach Unified. But because of the cost of coastal real estate, some are doubling up with roommates, driving long distances or moving to inland areas with cheaper housing, such as Bakersfield or San Bernardino, where lower rent makes it easier to whittle away at debt from student loans.

“As a state and as citizens, we have to ask how we better support this profession,” said Pavri, who noted that in a 30-year career a teacher can have an effect on thousands of young lives. “It’s the profession on which all others are built. It sets a foundation for young people to be successful later in life.”

The good news is that because of the shortage, jobs are plentiful, even if the paycheck isn’t. And a lot of teaching jobs come with great benefits as well as chances to earn extra by teaching summer classes, coaching teams or running clubs.

CSUN will soon be sending about 300 new teachers to Los Angeles Unified, which hires about 1,500 instructors a year on average to replace retirees. And an anticipated state shortage of as many as 100,000 teachers over the next decade makes job security look like a good bet.

Higher salaries would help fill the shortage, and so would waiving paperwork and credentialing fees, which run as high as $1,100.

At LAUSD, Supt. Austin Beutner is exploring the possibility of building housing for teachers, custodians, cafeteria workers and other employees on campuses that have underused acreage. The school district wouldn’t put up any money, Beutner told me, but if private and nonprofit developers get free land to build on, the housing will be cheaper.

He sent me a map that shows where LAUSD employees live, and a shocking number are as far out as Riverside, San Bernardino, Ventura and beyond. Commute times, according to district data, run as high as two hours and longer in each direction.

If 30 to 50 LAUSD campuses can accommodate 50 or so housing units each, Beutner said, “you can start to make a meaningful contribution. It’s a great service to the community and it’s equally important to us to attract and retain good employees.”

At CSUN, I found graduating students who intend to live with their parents, students who live with working spouses and will be fine financially, students considering a move out of the area, and students second-guessing their decision to be teachers.

“I made more money at one point waiting tables than I will probably as a first-year teacher,” said Barnaby Williams, who used to work at a Cheesecake Factory. He said he lives with a girlfriend who’s a teacher, but if at some point they’re not together, he suspects he’ll leave the area to teach or maybe find something else to do for a living.

I made more money at one point waiting tables than I will probably as a first-year teacher.

— Barnaby Williams

Students are all familiar with what’s known as first-year burnout, a phenomenon in which idealism butts up against the realities of bureaucracy, school politics, resource shortages, the demands of parents and the challenges from students.

Sean Saenz said he works on the side as a video editor and might do that full time if he doesn’t get a good teaching job in an area where he can afford to live. He said that as a student teacher and a substitute he’s watched teachers, even those at the high end of the pay scale, juggle coaching and clubs and teaching on weekends and summers, just to get by.

He said of one teacher in particular, “He’s beat.” And yet, Saenz said, that teacher is as passionate about teaching as anyone he’s met.

Keiri Ramirez is beyond the wondering. She’s ready to be a teacher.

Ideally, she’d love to own a house. But if she and her boyfriend get married and both teach and all they can afford is a one-bedroom apartment, she said, that’ll be fine.

“We kind of go with what our hearts want. We don’t really pay attention to the numbers,” Ramirez said.

The thought of sitting at a computer in an office, rather than standing before a class, was enough to keep her on track for her credential.

“I was a student at LAUSD and where I came from, the majority were Latino and black and I felt like I didn’t see a lot of women in the math field,” Ramirez said. “So in my last year of high school I knew that I wanted to be that person for someone.”

As she led class at Northridge Academy High, a student named Ashley Chacon whispered to me that she likes Miss Ramirez as a teacher. She’s easy to relate to, she said, because there’s not that much of an age difference.

I asked Chacon what career she’s interested in.

She said she thinks she wants to be a teacher.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.