For decades, Dicker and Dicker meant Hollywood glamour. Now its last furs are on sale

Lily Costa paced the aisles of Dicker and Dicker of Beverly Hills, her long French acrylics stroking the pelts.

Her son Zhivago was getting engaged. The family would cement his betrothal with a fur for the bride. The mink was on sale, but the groom’s father, Sonny Costa, still frowned at the price. Lily called the girl’s mother on FaceTime, hoping she could decide.

For the record:

1:43 p.m. Feb. 8, 2020Lorenzo Costa is misidentified as Zhivago in this article.

“Šukar, šukar,” the bride’s mother said in Romani as one floor-length fur coat after another was shown. Beautiful, beautiful. She wanted one, too. Lily had already picked a coat for herself, but if they left without something for their daughters, “you’ll be coming to our funeral,” Sonny warned the owner.

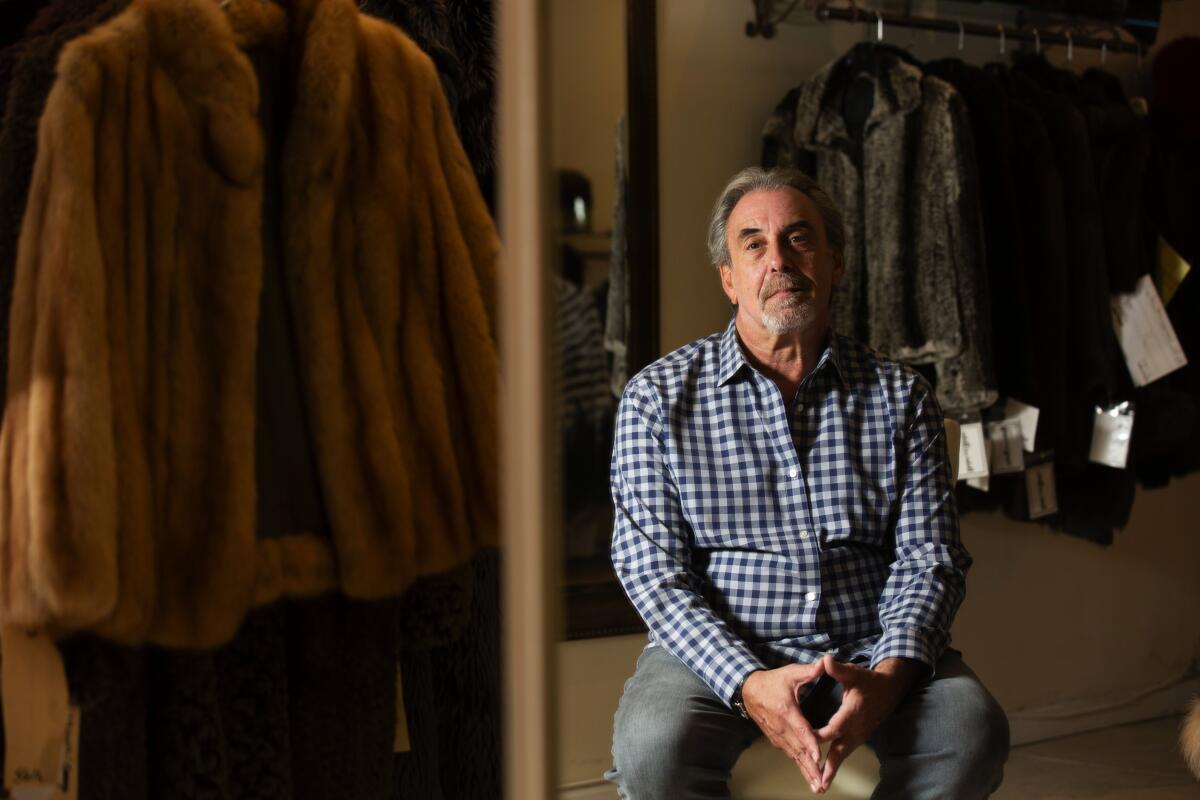

“Why, what are you serving?” owner Larry Becker said. The store had been closed for an hour, and his wife had just called to ask when he’d be home for dinner.

For 75 years, Dicker and Dicker of Beverly Hills styled itself as the apex of Hollywood glamour. Its silver fox and Russian sable were the stuff of game show grand prizes, elegant lures for “Let’s Make a Deal,” “Hollywood Squares” and “Queen for a Day.”

For most Americans, fur has since lost its luster. But Angelenos have always been a class apart. Among those who passed through Dicker’s doors on a recent weekday were a 19-year-old Persian Jew and a French Armenian octogenarian, a 51-year-old black stylist from Detroit and the middle-aged Romani couple from Pasadena, whose daughter screamed “I love it!” when a full-length white mink coat with voluminous fox-fur sleeves was modeled for her.

Some, like the Costas, were drawn by the display window. Others, like Faith Gomberg and Dwen Curry, had come to pay their respects. In September, California became the first state to ban the sale of new fur apparel. Though the law won’t go into effect until 2023, Dicker and Dicker will close its doors for good by end of the month.

“So many people are asking, why close now? You’ve got two years,” the fourth-generation furrier said. “But I spent 42 years doing this — I don’t want to be saddened by it,” Becker added, dusting off his hands. “I want to leave on a positive note.”

In December, he let longtime customers know he was liquidating. The response was enormous. Few who love it can resist mink on sale.

“Oh wow, that’s a great deal!” said 19-year-old Brandon Nisani, the firstborn among triplets, as he gawked at the $4,000 price tag that hung from his sleeve. “I look amazing right now.”

Nisani and his girlfriend had wandered in off the street, hoping the sale might distract from his grief over the death of Kobe Bryant. She was indifferent, but he was entranced, touching everything but returning over and over to the sapphire mink.

“It’s luxury,” Becker said to Nisani.

“It is,” Nisani said, turning from the mirror as though struck by the thought. “I feel like a boss, I’m not gonna lie.”

He admired his reflection at length, snapping selfies while his girlfriend chatted on the phone and urged him in Persian to please hurry up. His friends would covet it. His brothers would die. “I really want it — it’s a really good deal.”

“Convince your mom to get it,” his girlfriend said. “Then you can steal it from her.”

Supporters of the new law argue fur is outmoded, an opulent cruelty in the face of more advanced fibers. But for most of human history, fur was the only way to stay warm. Even today, only human hands can cut and sew it. Fur garments are stitched through with history, the attachment to them both aesthetic and ancestral. A coat is a lifetime investment — like parrots, most outlive their owners.

“My husband got me a ranch mink stroller” — a coat that falls near the knee — “and I had it remodeled into a jacket because I wear my fur,” said widow Virginia Higgins-Bland, 81. “I have one leather on the outside, shearling on the inside. It went to Obama’s inauguration on me, and I was toasty.”

Dicker and Dicker’s in-house artisan, Monika Herbig, specializes in such work, recycling dated styles and treasured heirlooms to be bigger, smaller, or simply something else. But no matter how often it’s reincarnated, a pelt will retain its luster only if it’s kept in cold storage — big business in L.A.’s blink-and-you-missed-it winter season.

“You cannot keep it at home — it’s not good for the fur,” said 83-year-old Barrett Sadock, a longtime customer who had come to shift inventory between her West Hollywood home and Dicker and Dicker’s cold storage. “You have to treat the fur the way you will take care of an animal.”

Becker said the company would find a new storage facility. But many were distraught.

“What am I going to do?” said Curry, the stylist, swanning into the showroom in an emerald satin shirt, Gucci sneakers and a chinchilla stole just as Nisani was being dragged away. “Where am I going to keep my furs now? I don’t want my babies on the street.”

Curry guessed he had about 10 pieces in storage, some his own, but many others belonging to family.

“This is from my grandmother,” he said, lifting a stole from its bag on the storage rack. The piece was made from half a dozen whole mink, each with glass eyes and genuine claws, sewn together by the snout. “She wore this when she was going to church; anywhere or anything important, she always had her mink on. I used to be scared of them — scared to death, because my uncles used to taunt me with them.”

Now, he was thinking of having them added to the collar of a denim jacket — to keep her memory near.

Like others, Curry grew wistful thinking about the store’s “little family,” the mood around him shifting between a class reunion and an Irish wake. Years ago, this stretch of South Robertson had been L.A.’s furrier row. When Dicker and Dicker closes, only one will be left.

“This is very sad for me. It’s a special place here,” said Gomberg, another longtime customer, as Becker poured her a second glass of champagne. “From the moment I walked in, it was mishpacha” — a family.

The old friends regarded each other, both misty-eyed. It was minutes to closing, the end of an era. They might never meet here again.

That’s when the Costas walked in.

“It’s very rare we walk into a furrier and walk out without anything,” the new customer assured the owner as the clock crept past 5 p.m. “But you’ve got to love it if you’re going to buy it.”

The whole store was stuffed with lovable coats. But as Becker noted earlier, “the popular items have the popular price.” So it was with the couple. They loved the mink, adored them. But they would pay only so much.

Becker’s salesman left at 5:30. Gomberg stayed, wandering the aisles with her champagne in one hand and ever more exotic furs in the other: ranch mink, sable, rex rabbit with chinchilla fur trim.

A reporter was conscripted to model, her figure deemed closest to the 18-year-old bride. The groom was summoned on FaceTime, then his sisters, then the bride’s mother, Stephanie Wain.

“I tell you, if it’s for the bride, I’ll do a thousand,” Becker said, rubbing his eyes.

“Šukar — it’s perfect,” the mother of the bride said. “The coat, she’ll wear it always.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.