No consensus on UC tuition hike as students protest and regents express mixed views

SAN FRANCISCO — University of California regents voiced starkly different views Wednesday on a proposed tuition increase for fall 2020, as consensus on the controversial issue failed to emerge.

During more than two hours of discussion on the first of a two-day meeting in San Francisco, one regent ruled out an increase while others leaned toward one of two plans UC officials have laid out that would raise tuition over five years.

Their debate came one day after Gov. Gavin Newsom announced he opposed any tuition increase as “unwarranted, bad for students and inconsistent with our college affordability goals.” His 2020-21 budget includes a $217.7 million increase in new permanent funding over last year for the UC system.

Regents had pushed back a vote, initially scheduled for Wednesday, to an unspecified later date because they failed to meet a 10-day public notice requirement to post details on any proposed changes to systemwide tuition and fees.

Regent Sherry Lansing said that voting for a tuition increase after Newsom had spoken out against one and provided such generous funding for UC seemed like a “slap in the face” and asked regents whether more dialogue with him would be possible.

“It just seems to me counterintuitive to move without more dialogue,” she said. “This is one of the most important and difficult decisions we have to make.”

UC officials say that increasing tuition would help raise more money for financial aid and university needs, as well as provide students, families and campus leaders with predictable changes in revenue and costs. Neediest students would benefit most, since any tuition hike would be more than covered by increased financial aid, which could also be used for housing, food and other needs.

One plan — to raise tuition and fees for all students annually by the cost of inflation — would amount to a projected 2.8% increase of $348 over last year, to $12,918 for fall 2020.

The second plan would raise tuition and fees once for each incoming class, called cohorts, but keep those costs flat for six years. Under that plan, the costs for the entering class of 2020-21 would increase over last year by 4.8%, or $606, to $13,176 for California undergraduates. The tuition of existing students would be frozen at their current levels.

But several regents pressed for alternatives to a tuition increase: lobby Sacramento for more state funding; increase philanthropy and control UC spending. One chart presented to regents showed UC costs growing by more than $2 billion by 2024, which took some of them aback.

“I’m concerned spending decisions are made as if money is no object,” Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis said.

She said she did not support either plan after traveling the state and witnessing what she called an “affordability crisis.” But she pledged to lobby for more state funds from legislators and Newsom.

Board Chairman John A. Pérez and Regent Lark Park, however, noted the myriad campus needs including class overcrowding, staff and labor working conditions, enormous pension liabilities, required seismic retrofitting, student hunger and homelessness. Pérez reminded regents that they approved many of the UC initiatives and programs, including recent collective bargaining agreements that will raise wages.

“We can’t pretend these rational good decisions we’ve made pay for themselves,” he said. “They don’t.”

Pérez reiterated his opposition to any broad-based tuition increase on all students but said he would consider the cohort plan to raise costs for incoming classes once and hold flat for six years. He noted that a UC Santa Barbara plan to guarantee financial aid for low-income students had significantly alleviated student stress and raised academic performance.

But Regent George Kieffer voiced support for a proposal to increase tuition on all students by the annual cost of inflation. Without steady increases, he said, UC’s core budget could be cut by 40% in a decade.

“I think our responsibility for the university is to look to a long-term goal, a long-term plan not kicking this forward every year,” he said.

Students, for their part, spoke out strongly against any increase. During public comments, several asked regents to consider the negative impact on those who would not benefit from more financial aid. They include students saddled with high medical expenses, LGBTQ students whose parents refuse to chip in for college, students who don’t know how to apply for financial aid and out of state students.

“We as an organization do not support making college more affordable for some students by making it more expensive for others,” Varsha Sarveshwar, UC Student Assn. president, said in remarks to the regents.

She and others urged regents to redouble efforts to secure more state funding rather than raise costs on students and families.

The proportion of state funding for UC’s core budget has plummeted from 84% in 1990 to 42% this academic year; tuition now accounts for a greater share.

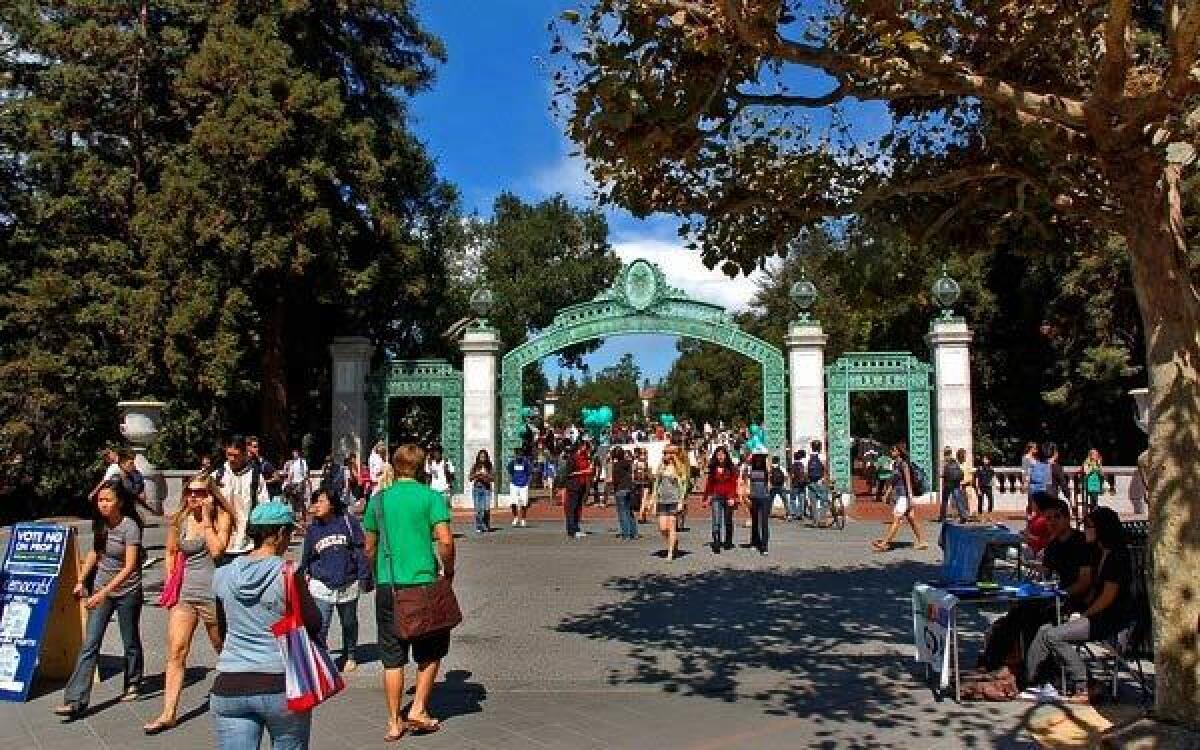

Tessa Stapp, a second-year UC Berkeley student majoring in political science, said she can’t afford any tuition increase because she already is so financially strained that she has to work more than 40 hours a week in three jobs. She often gets four hours of sleep a night and sometimes falls asleep in class.

She receives about $10,000 in annual financial aid and has taken out a $5,000 student loan but that doesn’t come close to covering the $30,000 cost of attendance when living and other expenses are figured in, she said.

Stapp’s father, a construction worker, is hard-pressed to help because medical bills have mounted after her mother was diagnosed with cancer and had to quit her job as an aide to special needs children. He does not support her, she said, because he thinks Berkeley is a “waste of money” and had urged her to attend a community college near their Oceanside home instead.

“The thought of a future student having to work the same amount I work to afford tuition is terrifying,” she said, her eyes tearing up.

Riya Master, a second-year Berkeley student studying integrative biology, said she is part of the majority of students from outside California who are middle class and have struggled to afford annual tuition increases. Undergraduate students from other states and countries would pay even more under the tuition plans: In addition to base tuition charged to all students, their supplemental tuition would increase $840, to $30,594, this fall under the first plan and an additional $1,440, to $31,194, under the second plan.

“They choose to use nonresidents as scapegoats,” she said of UC regents. “It brings so much pain to me all the time.”

Master, a Virginia resident, could have attended her state school but she and her parents dreamed of a “brighter future” at world-renowned Berkeley.

Other students objected to different tuition levels for different classes of students, as the cohort model would do.

“They’re trying to divide students and it will de-centivize them from working together to protest cost increases,” said Vassilisa Rubtsova, a Berkeley junior studying environmental economics and applied math.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.