Adam Schiff takes on Trump, calling him an ‘erratic hothead.’ Now he’s feeling the heat

WASHINGTON — Not during the fierce competition of Harvard Law School, or the rough-and-tumble of life as a federal prosecutor. Not when he convicted the first FBI agent accused of spying for a foreign government. Not even when he won one of the most furious campaigns for a seat in the House of Representatives, defeating a Republican who had relentlessly pursued President Clinton.

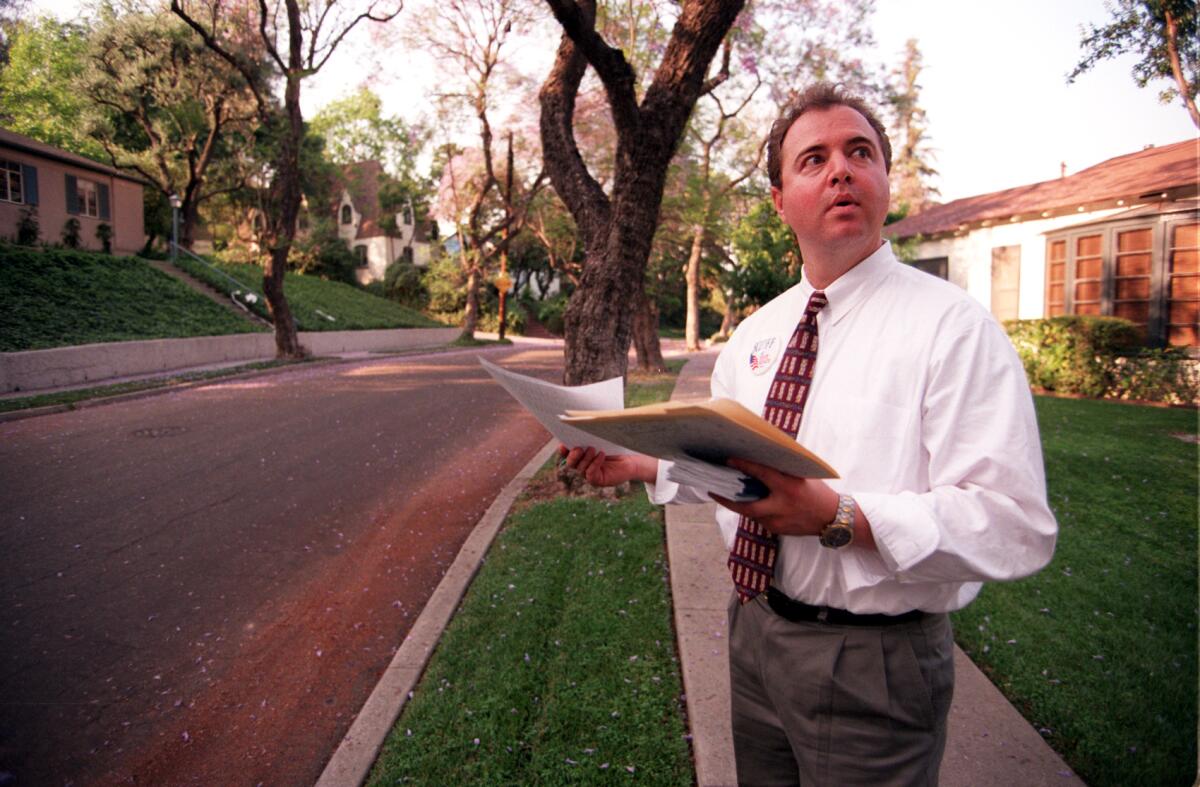

Not once in the political origin story of Rep. Adam B. Schiff does the record show him being labeled as “shifty.” But, then, the 10-term congressman from Burbank never faced an opponent quite like his current one, a president of the United States happy to turn a rival’s name into a potty joke and a schoolboy’s taunt.

To President Trump and millions of his loyalists, it’s now “Shifty Schiff,” though other insults will do. “Liar” and “traitor” skitter across the internet and even rained on Schiff at what was supposed to be a friendly event last month in his district. The relentless rebranding comes with a financial bonus for Trump’s reelection campaign — $34 for every “Pencil-Neck Adam Schiff” T-shirt sold.

Schiff initially countered Trump with gentle corrections, leading the New York Times to say that, as an attack dog, he was “more labradoodle than Doberman.” But his tone has hardened. In September, he compared Trump’s furiously debated phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to a mob boss engaged in a “shakedown.” Speaking with the Los Angeles Times recently, he had some salty new words for the president.

Democrats have responded with something like adoration. They line up for selfies and autographs. Some wear “I Stand With Schiff” T-shirts. His campaign even attempts to own the put-downs. Pencils labeled “This Pencil Neck Won’t Break” and “This Pencil Neck Will Investigate” go for $8 a pack.

This is Schiff’s reward for becoming not just Trump’s chief interlocutor, but superego to his id. In a hearing room on one end of Pennsylvania Avenue the poker-faced lawmaker presides, embracing Washington institutions and a belief that government can do good. On the other end, the unpredictable chief executive unleashes grievances against his opponents and encourages doubts about the government he leads.

Schiff had no idea he would end up here. The self-improvement obsessive earned a brown belt in karate, dabbled in Slovak and wrote screenplays before he committed fully to politics. His early academic career had him on a path to medicine.

When he first turned to elected office, he lost badly, then lost again, and again, before winning. Confronted with a president whom he has called the worst in modern history, he agitated some in his own party by hesitating to pursue impeachment. Now he is all in and, allies say, not retreating.

“They can try to scream at him. They can try to run him out of the room, but it’s not going to work,” said Barbara Boxer, the former senator from California, who encouraged Schiff to run for his House seat 20 years ago. “The moment has really found him, and he is ready.”

Schiff, 59, was named Wednesday as the lead among seven House managers of the impeachment trial, who, starting Tuesday, will try to persuade two-thirds of the members of the Senate to convict Trump of at least one of two articles of impeachment.

He knows the temperature is about to spike. Again.

“What I’ve discovered is that ... in an irrational time when you have an erratic hothead in the Oval Office, there is a real premium on not having your hair on fire,” Schiff reflected, sitting in a room off the House chamber. “I suspect that part of it is just my own temperament, which I couldn’t change even if I wanted to.”

::

Schiff is the youngest of two sons of Ed and Sherry Schiff. His parents were salespeople, his father a workaholic who traded in hats, then clothing, before opening a lumberyard. His mother came late to real estate and proved a natural, becoming a top salesperson.

A key memory for older brother Dan came when Adam was about 7, the family living in Danville, east of Oakland. Already a striver, Adam had determined that he would outdo the neighborhood boy who was the best “burp-talker.” His relentless faux belches wore on his brother’s nerves, until Dan threw his jacket and the zipper caught Adam’s mouth.

Dan Schiff pleaded for Adam to come up with a story, any story, to tell their parents. Adam howled.

“There was all this blood. But what triggered him was that I was asking him to lie,” said Dan Schiff. “The fact that he was being steered to a lie, that really rankled him.”

At Monte Vista High School, Dan Schiff took home awards and victories for debate, finishing third in the state, while Adam did not fare as well. “He was the tortoise, who kept at it, who never got dejected,” said the elder Schiff, noting that his brother would become valedictorian.

Despite being accepted to one of the top medical schools in the country, UC San Francisco, Schiff thought his interest in public service would be better served by law school.

“To get a Jewish mother that close to ‘my son, the doctor,’ and then snatch it away is a very cruel thing to do,” Schiff joked in an interview with WNYC.

In 1987, he joined the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles. In a hothouse of Type A personalities, Schiff stood apart for his almost sentimental belief in the system.

When lawyers met to present their cases to each other, colleagues remember Schiff droning on in copious detail. Some of the wiseacres in the room would feign hanging themselves or slashing their wrists. “He would just proceed with what he was saying,” said a former colleague, who asked not to be named while poking fun at Schiff. “He was completely undaunted by it.”

“In an office filled with earnest and ambitious people, Adam stood apart for his earnestness and ambition,” said former prosecutor Jonathan Shapiro, co-creator of the Amazon legal thriller “Goliath.”

His officemates wondered: Who else among them — dispatched to Slovakia to help with criminal justice reform — would have taken the time to become relatively facile in Slovak? Another former colleague, Jeffrey C. Eglash, the former inspector general of the Los Angeles Police Commission, said that Schiff seems unchanged three decades later:

“He is Mr. Rogers.”

Schiff’s signature moment came with the prosecution of Richard Miller, an incompetent finagler who also happened to be an FBI agent. Miller had fallen for a vivacious Russian spy, Svetlana Ogorodnikova. She promised Miller cash, sex and gold in exchange for documents. Miller’s first trial ended in a hung jury and the second in a conviction, overturned by an appellate court.

One of Miller’s defense attorneys, Stanley Greenberg, said his young adversary in the third trial was “no Michael Avenatti,” adding: “The lawyers I find the hardest to confront are the low-key guys who just present the facts and let them paint a picture. He was in that category.”

Miller ended up sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. Schiff told Politico he learned a lot “about Russian tradecraft ... the vulnerabilities they look for.” Three decades later, as he began investigating Trump, he found those lessons useful.

::

Decades ago, Schiff was working out with one of his best friends, Karl Thurmond, a common pastime for the sometime marathoner and triathlete. That evening in the mid-1980s, as the two ran down San Vicente Boulevard, Schiff spoke of how he admired John F. Kennedy. He added he had a dream of his own — that he, too, might one day ascend to the White House.

That’s the way Thurmond remembers it, anyway, though Schiff says he has no such recollection. What’s clear is that by 1991, Schiff was looking for a new path beyond his work as a prosecutor. He saw an opportunity when a state Assembly seat opened west of downtown Los Angeles.

Schiff drained the $13,000 in his 401(k) to to fund his candidacy, his brother recalled. One novel pitch, “Shoes for Schiff,” had him promising to collect shoes from voters and donate them to the homeless. A complication, one friend recalled: With no one else to do the job, the candidate spent crucial time just before the election collecting the castoffs himself. (Schiff believes volunteers handled the task.)

The fledgling candidate bridled at the idea he had to speak in pithy sound bites. His speeches meandered.

“He was pretty much a stiff,” said Brian Hennigan, another friend and former prosecutor, who has supported Schiff in all his campaigns. “He had a sense of humor, but it just didn’t come out in that setting.”

Schiff finished 11th out of 15 candidates. He won 710 votes. Friends recall being mortified, while Schiff seemed hardly fazed, chalking it up as a lesson learned.

Moving to Burbank, he would lose two more races for Assembly to another attorney, a Republican named James Rogan. But he came closer in each contest.

In 1996, Schiff’s time finally arrived. He ran against Republican Paula Boland for a vacant state Senate seat representing Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena and parts of Los Feliz. As he would in future wins, he depicted himself as the moderate, action-oriented candidate. Boland appeared to be an overzealous champion of San Fernando Valley secession from Los Angeles.

Schiff also benefited from the assistance of one phone-bank fanatic, Sherry Schiff, who would not let voters off the phone until they pledged to support her son.

“So many people would tell Adam, ‘A woman claiming to be your mother made me promise to vote for you,’” recalls Dan Schiff. “And he would say, ‘That was my mother!’”

Four years later, Schiff had another shot at Rogan, who had ascended to the U.S. House, where he was one of the outspoken managers who helped prosecute President Clinton’s impeachment case. Unlike the president who would be tried two decades later while struggling to reach a 50% approval rating, Clinton’s popularity hovered around 65%.

Money poured into the 27th Congressional District from around the nation. Schiff claimed support from Hollywood liberals, like entertainment mogul David Geffen, infuriated by the impeachment of Clinton. Spending about $11 million total — then the most expensive House race in the country — both sides bombarded voters with their pitches.

The candidates aired 140 ads a day — on Armenian American cable television alone. One pamphlet from the California Republican Party claimed Schiff had made it easier for California prison inmates to get “Satanic bibles.”

Schiff won by nearly 9 percentage points.

Arriving in Washington, he joined the Blue Dog Democrats, known for fiscal restraint. He helped create his party’s Study Group on National Security, inviting guests including Newt Gingrich and former Georgia Sen. Sam Nunn for deep dives on foreign policy issues. The wonky group earned the nickname “the Nerd Caucus.”

Schiff passed legislation to limit the nuclear materials that could be gathered by countries that withdrew from a nuclear proliferation treaty. He formed a congressional caucus supporting freedom of the press. He won money for a regional lab to speed the processing of crime scene DNA in his district, which includes Pasadena and Glendale. His long work for a resolution recognizing the Armenian genocide of the early 20th century finally paid off in October, when the House approved the measure.

“We cannot cloak our support for human rights in euphemisms,” Schiff had said. “We cannot be cowed into silence by a foreign power.”

It’s hard to recall now, but in a time before Trump, Schiff got along amicably with Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Tulare), the top Republican on the Intelligence Committee. Rep. Peter T. King (R-N.Y.) recently recalled Schiff as “a moderate guy,” adding: “We trusted him. We would talk with him.”

But in King’s mind, Schiff became too prosecutorial and too arrogant during the impeachment hearings.

“It was just like a runaway hearing,” King said. “A runaway proceeding, where the ending was already written.”

::

The recognition of the mass killings by Turkish forces had been a major objective of Armenians, and therefore a priority in Schiff’s district, where the largest concentration of Armenians outside that country live.

Official U.S. recognition had been tied up for decades because of America’s strategic alliance with Turkey. When the House vote came in, the Armenian National Committee of America wanted to celebrate with an event to thank Schiff.

The gathering seemed like it might provide a respite from Washington’s pre-holiday partisan siege. But moments after Schiff began addressing the auditorium someone shouted, “Liar!” Others joined in. A few held signs that read, “Don’t impeach.” The bulk of the crowd, rallying to Schiff’s side, moved to end the disturbance. Scuffles broke out.

Schiff looked on helplessly from the stage. “Adam is very even-keeled, and I know he was fine,” said David McMillan, a friend of more than 30 years, who had dinner with Schiff that night. “But I could tell he was a little rattled by it.”

When Trump’s Senate trial ends, Schiff will remain as chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, a position that will allow him to continue to scrutinize the president.

Beyond that, Schiff’s political future remains unclear.

A much-discussed run for the Senate did not materialize in 2018, when California’s senior senator, Dianne Feinstein, eschewed retirement. Schiff also has been named as a possible successor to his close ally, Nancy Pelosi, as speaker of the House, though she shows no sign of retiring in the near term. A Democratic presidential victory in 2020 could mean a shot at a Cabinet post for Schiff.

In 2018, on a visit to New Hampshire, Schiff basked in speculation that he might make a presidential run.

“It’s fun coming up here,” he said. “And I enjoy the idea that I might cause certain heads at Fox News to explode.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.