Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget envisions an activist agenda but limits higher spending

SACRAMENTO — For the seventh time in eight years, California’s government is poised to collect a sizable cash surplus under projections in the $222.2-billion state budget Gov. Gavin Newsom submitted to the Legislature on Friday — a remarkable streak even in the face of steadily higher spending, most notably on K-12 education and services for low-income residents.

Those programs would remain the focus of government growth under the plan unveiled by Newsom. Elsewhere, he urged lawmakers to limit their requests for more spending in light of expectations that the state and national economies will grow more slowly in the immediate future.

“While we’ve enjoyed 11 years of economic growth and expansion, that is not a permanent state,” Newsom told reporters at the state Capitol.

But the budget crafted by Newsom is hardly cautious. Although it seeks limited growth in long-term commitments, the governor proposes to expand state government’s reach into policy areas that have historically been the purview of local and federal government. Those include new efforts to combat a worsening homelessness crisis, lower the cost of prescription drugs and better protect the rights of California consumers.

“I’m very proud to be a Californian. I’m proud of this state,” Newsom said. “But I am not naive about the areas where we’re falling short.”

Whether his fellow Democrats in the Legislature will agree to follow his lead is unclear. So, too, is whether the governor might soften his stance on year-over-year spending once a final budget is enacted in June. In 2019, his first year in office, Newsom signed a budget that boosted ongoing state expenditures by $4 billion. The independent Legislative Analyst’s Office has since estimated those pledges will cost close to $6 billion a year once fully implemented, with some spending increases to take effect this spring.

In the newly proposed budget, health and human services spending will grow by $5.5 billion, which includes higher wages for in-home care workers and an 18-month extension of last year’s action to eliminate taxes collected on the sale of diapers and feminine hygiene products. Democratic legislative leaders also applauded proposals to expand preschool options for low-income families and to expand access to paid family leave to more California workers.

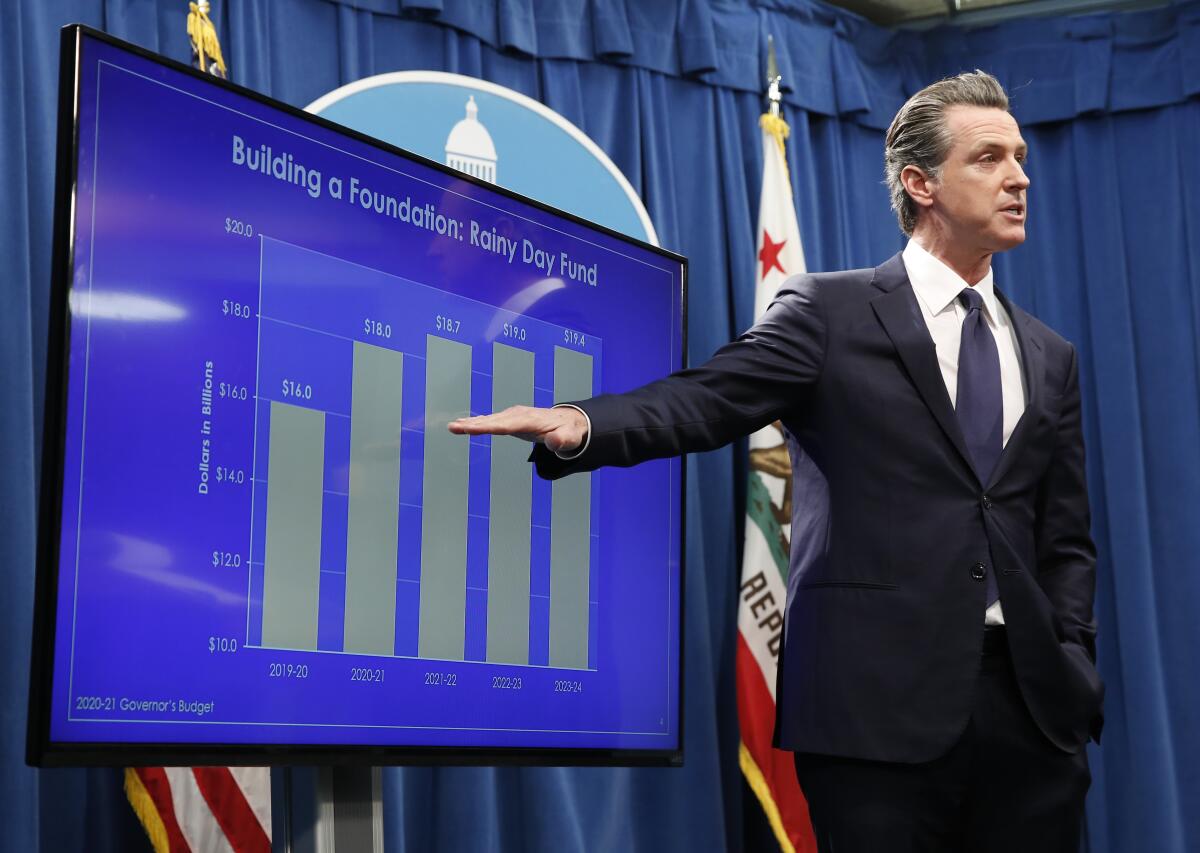

Newsom’s budget reflects $153 billion in new spending from the general fund, the state’s primary bank account. The vast majority of projected windfall revenue would be stashed away in California’s so-called rainy day fund. By summer 2021, the reserve account would grow to an estimated $18 billion — more backup budget cash than at any other time in state history.

The spending plan offers some limited versions of Democratic priorities. Most notable is Newsom’s decision to support coverage in the state’s Medi-Cal program for all residents older than 65, regardless of immigration status. The $80.5-million expansion of the healthcare program, in which eligibility is tied to income, builds on last year’s decision to fully cover teens and young adults in the U.S. illegally. But the change won’t take effect until 2021 and the governor has yet to embrace coverage for all immigrant adults, an idea with estimated annual costs that could run as high as $1 billion.

Some of the most ambitious proposals were unveiled in the days leading up to Friday’s formal submission of a spending plan. Those efforts include more than $1.4 billion to shelter and offer healthcare to California’s homeless population, with more than half of the money to be offered as direct cash subsidies to local services. While lawmakers are expected to agree to the extra money, other parts of Newsom’s new homelessness plan could be a tougher sell — most notably, his proposal to revamp rules governing mental healthcare spending funded by a tax on millionaires that was imposed by voters in 2004.

The governor has asked the Legislature to sign off on a first-in-the-nation proposal to market and sell generic prescription drugs to the state’s residents under a government-run operation. The effort comes on the heels of Newsom’s push last year to harness the purchasing power of state and local agencies in hopes of lowering costs paid by taxpayers.

Newsom’s new budget also proposes the creation of a state-run consumer protection agency, which would monitor the business practices of financial institutions and oversee debt collection companies. The effort is largely in response to the diminished activity of the federal government’s consumer watchdog operations under President Trump.

The consumer oversight and drug pricing efforts are the budget plan’s most striking proposals to continue a three-year effort by state lawmakers to position California as a policy and political counterweight to Trump. Taken as a whole, the effort has produced an agenda to either defy or ignore what happens in Washington and stretch the boundaries of what any single state can do on its own.

Last year, Newsom and Democratic legislators signed off on a state mandate to purchase health insurance after Republicans in Washington effectively repealed the national requirement under the Affordable Care Act. Californians who fail to get insured would have to pay a fine when filing their state tax returns in 2021 — at least $2,000 for a family of four, state officials said Thursday.

Meanwhile, Newsom’s administration has sought to reinforce California’s singular path toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The state recently struck agreements with automotive companies on vehicle emissions standards, hoping to circumvent Trump’s cancellation of a longstanding program in which California set stricter rules than those required in other parts of the country. The still-unsettled topic has produced some of the most significant clashes between states and the federal government in recent months.

Trump and Newsom have clashed repeatedly in recent weeks over California’s ever-worsening homelessness crisis. Federal statistics released Monday estimate that more than 150,000 men, women and children in the state experienced homelessness last year. The president and Ben Carson, his secretary of Housing and Urban Development, have warned that federal officials may take action on their own to mitigate the problem. Those tensions have eased somewhat in Los Angeles, where city officials said Thursday they are seeking to work in partnership with federal officials on a variety of efforts.

Newsom, who frequently lambastes the president on social media, insisted Friday that the state isn’t waiting for a response on requests for help that have been sent to Trump.

“He’s tweeting; we’re doing something,” the governor said. “We have a real plan, real strategies. We’re building on what works. We don’t need him to identify this problem.”

Newsom also said the state would step in to address concerns over the growing popularity of vaping that had not been addressed in Washington. The budget calls for a new tax on e-cigarette products based on the amount of nicotine they contain. Newsom said the use of vaping devices by children “scares the hell out of me as a parent” and predicted the tax increase would pass handily in the Legislature.

Elsewhere, the governor’s new budget seeks to boost the state’s efforts on fighting and preventing wildfires, while providing new funds for emergency response programs. And it proposes a $1-billion, four-year effort to encourage new approaches to fighting climate change by offering low-interest loans to small businesses and organizations with ideas on efforts such as recycling and low-carbon transportation.

As in years past, the majority of state government expenditures would go toward education and healthcare services. Newsom’s budget projects $84 billion in general fund spending on K-12 education and community colleges. When combined with other state and federal funds, per-pupil spending in K-12 schools would rise to $17,964.

Legislators will begin a detailed review of Newsom’s budget later this month. Broad policy discussions on spending priorities generally dominate the winter and spring months in Sacramento, with detailed budget negotiations occurring after April tax revenue is collected. By law, the Legislature must send a completed fiscal plan to Newsom no later than June 15.

Times staff writer Phil Willon contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.