So many allegations of rape against Weinstein and others, so few charges

More than two years have passed since the #MeToo movement gained widespread traction. Scores of women have come forward, accusing media mogul Harvey Weinstein and other Hollywood heavyweights of sexual assault. The culture and the conversation have changed when it comes to matters of consent.

But to date, charges have been filed in Los Angeles County in only two cases. Both are against Weinstein. Both weren’t filed until Monday.

Why hasn’t more happened?

Just ask Phyllis Golden-Gottlieb, Victoria Valentino and Dominique Huett.

In November 2017, Golden-Gottlieb told Los Angeles police that CBS Corp. Chief Executive Leslie Moonves had invited her to lunch. But instead of driving to the restaurant, he parked on a secluded side street. That’s where he grabbed her head, she said, forced it into his crotch and ejaculated into her mouth.

Three months later, the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office announced that it would not file charges. It was just one of several incidents Golden-Gottlieb, now 83, had reported. But they all happened between 1986 and 1988, when she worked with Moonves at Lorimar Productions. Moonves has maintained that his contact with her was consensual; he later resigned under pressure.

“I wanted him to be accountable,” Golden-Gottlieb told The Times in a 2018 interview when Moonves left CBS. “This has been with me the whole time. I don’t think it was every day, but many days.”

Valentino, a former Playboy model, alleged Bill Cosby had drugged and raped her at an apartment in the Hollywood Hills in 1969. She didn’t come forward until 2014, when she was triggered by a male comedian joking about Cosby the rapist. Although other alleged Cosby victims had told their stories for years, no one paid attention until a man spoke the words.

“Suddenly this red rocket of anger exploded inside my head,” said Valentino, who is now 77. “I thought, ‘A woman has been trying to be believed for 30 years, yet all it takes is one guy to make a joke about it in a stand-up routine in Philly, and suddenly everybody believes him.’ Something about that just pushed me over the edge.”

Cosby was convicted on sexual assault charges in 2018 in Pennsylvania and sentenced to three to 10 years in prison. Valentino helped get the California law passed that removed the statute of limitations for certain sex crimes committed after Jan. 1, 2017. Before the law changed, prosecution of felony sex offenses generally had to begin within 10 years of the alleged attack.

Unlike Golden-Gottlieb and Valentino, Huett did not run up against the statute of limitations after she reported an alleged sexual assault to Beverly Hills police in 2017. Weinstein, the actress said, had lured her to the bar at the Peninsula Beverly Hills hotel in 2010, ostensibly to talk about her career.

Instead, she said, he led her up to his room. He gave her champagne. He put on a bathrobe. He insisted that she give him a massage. And then, she said, he performed oral sex on her, although she repeatedly resisted. The district attorney’s office has not filed charges against Weinstein in the case.

But Huett, who is now 37, said a prosecutor told her on Tuesday that her case is one of three against Weinstein that are under review. She said she initially came forward to reduce the stigma centered around sexual abuse.

“As we know, many people affected by sexual violence don’t speak out right away, for fear of retribution, retaliation, black listing,” she said. “I knew a lot of people were suffering in silence.”

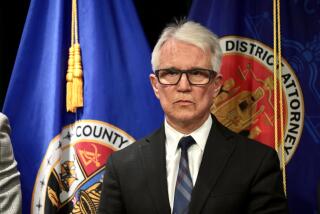

Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey explained Monday morning why her office had filed charges against Weinstein in just two cases, for attacks he allegedly committed against Jane Doe No. 1 and Jane Doe No. 2. Just hours earlier, the once-powerful entertainment bigwig had hobbled into a New York courtroom, leaning heavily on a metal walker, at the beginning of his trial for similar alleged crimes on the East Coast.

“Each of these victims told at least one person about the assault in 2013,” Lacey said during a Monday press conference in Los Angeles. “They reported the crimes to police in 2017. … In all, eight women came forward to report that they were sexually assaulted by the defendant in Los Angeles County.”

Lacey also laid out — more or less — why her office had not filed charges against Weinstein and other members of the entertainment establishment based on dozens of additional allegations. More than 40 other cases have been presented to her office in the past two years; all, she said, have been lacking in one of two ways.

“The alleged crimes were too old to prosecute,” Lacey said. “Or there was insufficient credible evidence to file charges against the defendant.”

The first is hard to argue. The second is where the trouble begins. Nearly half a century after the first rape crisis centers were launched in the United States, sexual assault allegations are still Rorschach tests for everyone involved — the victim, her (it’s usually her) friends and family members, police officers, district attorneys and the public at large.

More often than not, women choose not to report sexual assault to the authorities — or even tell those closest to them. Part of the issue is shame, having to describe horrible acts to loved ones and strangers. And then, said Colby Bruno, senior legal counsel at the Victim Rights Law Center, many women feel responsible, that they did something wrong, had too much to drink, shouldn’t have been there, shouldn’t have trusted him, waited too long to call the police.

There’s also the justice system itself, with its necessary scrutiny in the aftermath of trauma, she said. “As much as I want to believe — and do believe — that many DAs have come further than where we were, you can just imagine hearing from someone who doesn’t know you say, ‘There are a few inconsistencies in your story.’

“That is the message to the victim that, ‘You are not credible’,” she continued. “Words like that pass through DA’s offices, investigators’ mouths, even victim advocates’ mouths.”

The impact on a victim of sexual assault can be enormous.

Stacey Cooper, who said she was drugged and raped 17 years ago by a man she had formerly dated, decided not to report the alleged assault to Los Angeles police. A close friend who had reported being sexually assaulted walked her through the legal process and what it felt like, step by step. She told Cooper, “I will support you, but you need to know what it’s like.”

Cooper was at a party in Los Angeles County when she accepted a drink. Then, she said, “it was lights out and waking up to flashes of this person on top of me, and I couldn’t move. When I woke up in the morning, I still couldn’t use my legs. It hadn’t worn off completely.”

She went home and sobbed in the shower. She went to her gynecologist, didn’t get a rape exam, tried to put the attack behind her. Several years later, she said, she started having seizures that she attributed to the trauma of being raped. At the time, she was a personal trainer with a thriving business. Today, she counsels women who have been through trauma and speaks out about the lasting impacts of rape.

Some days, she said, she wishes she had reported the assault to police. Reporting, she said, “is a bold, courageous move.” But she also knows that people who have been sexually assaulted must be allowed to decide for themselves.

When you report, she said, “your life will be torn apart, you will be discredited, you will relive the trauma. You have to make the choice that’s best for you when you want more than anything in the world to be that brave, courageous woman.”

But what about when someone who has been sexually assaulted decides to report and then nothing happens? When she gins up that courage and the district attorney’s office decides not to prosecute?

As Lacey said Monday, in the past two years her office has received more than 40 cases of alleged sexual assault stemming from the entertainment industry and the #MeToo movement. Of the eight that involved Weinstein, charges were filed in two of them, three took place outside the statute of limitations and three are still being reviewed. .

Actress Jessica Barth’s is one of the 40-plus other cases. And she is furious.

Lacey’s office is currently reviewing a police investigation into a 2012 incident in which Barth alleges her manager at the time drugged and sexually assaulted her. A year earlier, at the Peninsula Beverly Hills hotel, Barth said Weinstein alternated between offering to cast her in a film and demanding a naked massage in bed.

“LADA Jackie Lacey states that in order to file a sexual assault case, prosecutors must be able to convince 12 jurors, beyond a reasonable doubt; the question is, what is considered reasonable,” Barth said in a written statement Tuesday. “What seems unreasonable is until today and since 2017, more than 40 sexual assault cases have been presented to the LADA’s office yet ZERO have been filed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.