1.4 million California kids have not received mandatory lead poisoning tests

More than 1.4 million children covered by California’s Medicaid healthcare program have not received the required testing for lead poisoning, state auditors reported Tuesday, and the two agencies charged with administering tests and preventing future exposure have fallen short on their responsibilities.

The critique, issued by the California state auditor, focuses on both the administration of lead tests to children in Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid healthcare program that pays for a variety of medical services for children and adults with limited income and resources, and the activities of the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, which helps communities increase awareness of the hazardous material, reduce exposure to lead and increase the number of children who are assessed and appropriately tested for elevated lead levels.

The 81-page report found that hundreds of thousands of children who should have been tested for elevated lead levels have not received all of their state-mandated tests, and the California Department of Health Care Services and the California Department of Public Health — the two agencies responsible for preventing and detecting lead poisoning across the state — are to blame.

The California Department of Health Care Services “has not met its responsibility to ensure that children enrolled in Medi-Cal receive required tests ... to determine whether they have elevated lead levels,” the report said. “Similarly, the California Department of Public Health, which is charged with the prevention and management of lead poisoning cases, has failed to focus on addressing lead hazards before children are exposed to them and has not met legislative requirements concerning lead poisoning.”

State law generally requires that children under the age of 3 enrolled in Medi-Cal receive tests for elevated lead levels. Lead is a toxic metal found in the air, soil and drinking water of some schools and homes that is highly damaging when absorbed into the body. Children younger than 6 are especially vulnerable to lead poisoning and its harmful effects, which can include a decreased IQ, as they absorb the toxic metal more efficiently than adults and are less likely to eliminate it through waste.

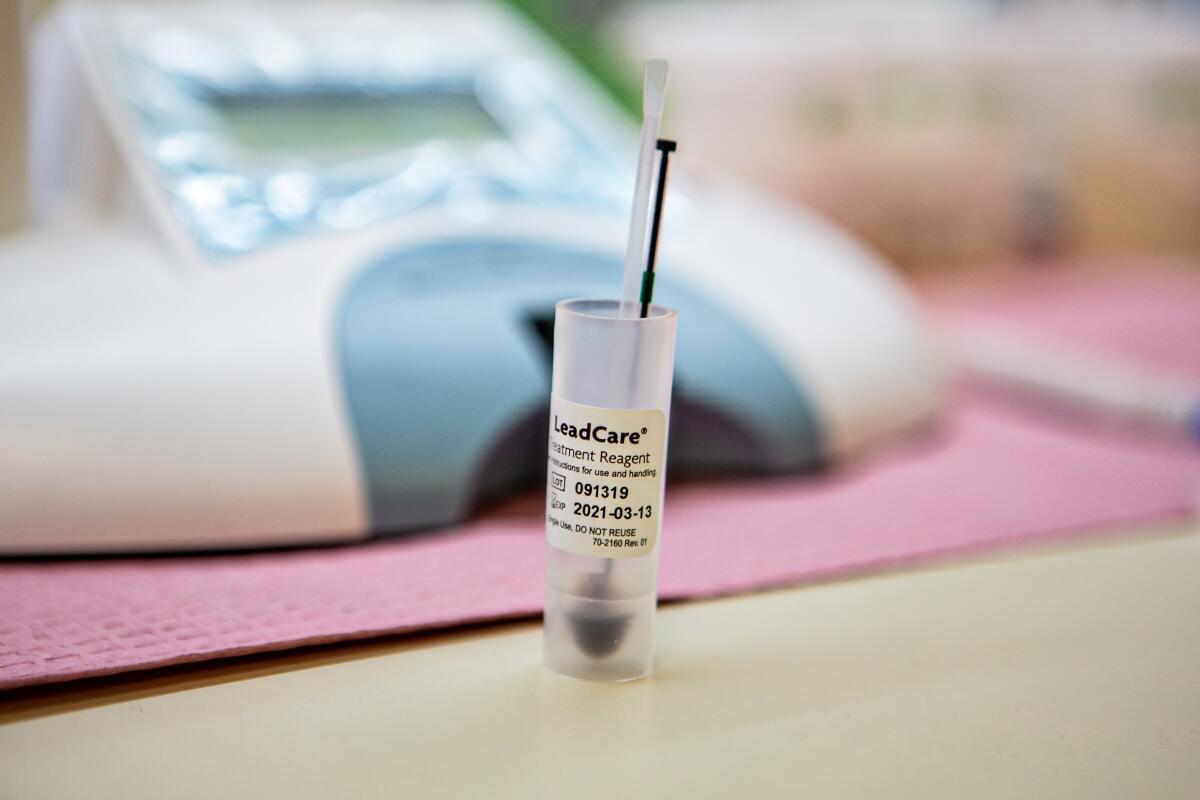

The best way to determine whether a child is exposed is with a blood test. It’s measured in micrograms, for every deciliter of blood. The report defines childhood lead poisoning as any quantity of 10 micrograms or more — the threshold at which healthcare providers are required to take action to reduce lead levels, though studies indicate even lower amounts of lead in the blood have severe consequences on a child’s normal development.

A review of the healthcare services department data found that nearly half of the 2.9 million 1- and 2-year-olds enrolled in Medi-Cal did not receive any of the required tests, the report said, and another 740,000 children missed one of the two tests. Federal Medicaid data from 2017 show California ranked 31st in the country for providing lead tests to infants.

“The rate of eligible children receiving all of the tests that they should have was less than 27%,” the report said. “Many of these children live in areas of the state with high occurrences of elevated lead ... making the low testing rates even more troubling.”

As part of the report, auditors analyzed the number of children with lead poisoning, the number of tests Medi-Cal-covered children ages 1 and 2 should have received and the number of tests that children those ages missed from 2013 through fiscal year 2018. The information was broken down by census tracts throughout the state.

In 2017, about 10,000 children statewide had elevated levels of lead in their bodies.

In San Diego County, data show more than 3,300 children under the age of 6 had lead poisoning, ranking the second highest in the state behind Los Angeles County, which had more than 12,600 lead poisoning cases.

The totals could be even higher. According to the audit, 1- and 2-year-old children in both counties missed nearly 60% of the lead tests they were supposed to receive, and the totals for some census tracts were removed from the publicly available database to protect the identity of patients.

“Without these tests, healthcare providers do not know whether these children are suffering from elevated lead levels and need treatment,” the report said. “Despite low lead testing rates, [the healthcare services department] has only recently begun developing an incentive program to increase testing and a performance standard for measuring the extent to which managed care plans are providing the tests.”

According to the report, the state’s public health department has also failed to identify high-risk areas, a step they recommend the agency take immediately, and take steps to abate lead risks in those locations.

The department instead contracts with local agencies that increase testing, provide follow-up services for children with lead poisoning and eliminate lead in the environment, but these programs only monitor homes of children who have already been exposed, preventing further exposure but failing to protect children who have not yet been tested.

“Because it has not completed this analysis, [it] lacks information on the locations where the risk of lead exposure is most significant,” auditors said. “If [the department] knew where the highest risk of lead exposure was, it could prioritize the resources it has to reduce the incidence of excessive lead exposure in those areas and better prevent lead exposure — the requirement established in state law.”

State and federal governments for decades have been working to prevent childhood lead poisoning, which skyrocketed in the 20th century as the use of lead gasoline increased, but concern about the toxic metal has intensified in recent years, particularly after corroding pipes in the city of Flint, Mich., led to widespread lead contamination in its water system.

The city decided in 2014 to draw its public water supply from the Flint River to save costs while the city worked on a permanent pipeline to Lake Huron. Despite resident complaints about the water’s appearance and odor, city officials maintained that the water was safe to drink.

Later testing revealed that the lead levels were dozens, or in some cases, hundreds of times higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended threshold.

As a naturally occurring element, lead was often used in paint, piping and other building materials. State and federal regulations now restrict its use, but lead in plumbing remains a hazard as old pipes corrode and chemicals seep into the drinking water.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, severe lead poisoning can lead to coma, convulsions and death. Lower levels cause more subtle symptoms, gradually impairing children’s brain development and leading to irreversible damage including a reduced IQ, attention problems and antisocial behavior. Health issues from lead exposure include anemia, high blood pressure, kidney problems and immune and reproductive disorders.

The report said DHCS should prioritize its effort to adopt a performance standard that monitors testing progress and require contracted healthcare plans to identify untested children and alert their doctors.

Auditors also recommended, among other things, that CDPH immediately identify the high-risk areas throughout the state and update how funding is distributed based on the findings.

To help the health department contact families and monitor lead tests results, auditors recommended that legislators amend state laws to require labs to submit contact information along with children’s lead test results.

Schroeder writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.