Appeals court throws out case against four social workers in Gabriel Fernandez case

Four years ago, when L.A. County prosecutors filed criminal charges against the social workers who left 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez in the home with his mother and her boyfriend despite multiple investigations into alleged abuse, the case stood as a stern warning to child protective caseworkers across the country.

Mishandle a case badly enough, the charges seemed to say, and you, too, might face felony child abuse charges.

“These social workers were criminally negligent,” Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey said at the time. “They should be held responsible.”

But this week, the landmark case — one of only a handful of such prosecutions nationwide — absorbed a crippling blow, when a state appeals court threw out the charges, saying there was “no probable cause.”

The 2nd District Court of Appeal justices ruled that the case hinged, in large part, on whether the four social workers had a legal duty to “exert control” over Gabriel’s abusers — his mother, Pearl Sinthia Fernandez, and her boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre. Both have been convicted of murdering Gabriel, whose May 2013 death led to far-reaching reforms within the county’s child welfare system.

“Although there may be consequences to social workers who fail to fulfill” their duties, the appellate opinion reads, “the consequences do not include criminal liability for child abuse.”

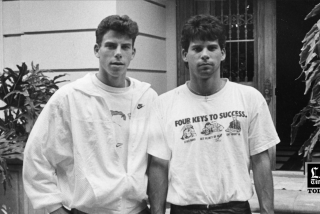

With their 2-1 ruling, the justices tossed out the 2016 criminal charges filed against former county Department of Children and Family Services employees Kevin Bom, Stefanie Rodriguez, Gregory Merritt and Patricia Clement — one felony count of child abuse and one felony count of falsifying public records for each defendant.

The decision, which the district attorney’s office still could appeal to the California Supreme Court, troubled Gabriel’s cousin, Emily Carranza.

“I’m a little disturbed and disappointed in the judicial system,” she said, adding that she hopes the district attorney’s office will appeal. “What kind of message are they sending to social workers? If you make a mistake, make sure you cover up your tracks? I’m angry.”

Asked if the district attorney’s office would appeal, Greg Risling, a spokesman for district attorney’s office, said, “We’re in the process of reviewing the opinion.”

The recent ruling stands in stark contrast to earlier decisions from two L.A. County Superior Court judges.

During a preliminary hearing in 2017, Judge Mary Lou Villar ruled that there was enough evidence to hold the social workers over for trial, saying she believed that the county employees had mishandled evidence of escalating abuse and failed to file reports about what was happening in the boy’s home within a timely manner.

“Red flags were everywhere,” the judge said.

Defense attorneys quickly filed a motion asking another judge to throw out the case. But in September of 2018, Judge George Lomeli, who presided over Aguirre’s murder trial, agreed that the case should proceed to trial.

Gabriel’s death had been “foreseeable,” Lomeli said, and the defendants — who he noted had overruled a scoring system intended to detect whether a child was in danger — had demonstrated “an improper regard for human life.”

A synopsis of the case laid out in the appellate opinion published Monday offers bleak details about Gabriel’s final months.

Early in 2013, after a counselor was assigned to do home visits with the family in Palmdale, Fernandez showed the counselor what appeared to be a suicide note written by Gabriel, which included a drawing of two upside-down characters.

“I love you so much that I will kill my sowf,” it read, according to court documents. “I love you in till you diy.”

Eventually, records show, after Fernandez refused to continue counseling, Clement, one of the social workers, recommended that DCFS close the case. But before officially closing it out, she used a risk-assessment rubric, which determined that the family scored a six — a “high” score. High-risk cases can’t be closed unless a supervisor makes a “discretionary override,” which is what happened, according to court documents, when Merritt, a supervisor, downgraded the case to “moderate.”

In early May 2013, about a month after the case was closed, Gabriel’s first-grade teacher called Rodriguez, another of the social workers, and left a voicemail saying that Gabriel had returned to school after a long absence with a red eye, skin peeling from his forehead and scabs. The social worker didn’t respond to the teacher’s messages, according to court documents.

Days later, Fernandez called 911 and when paramedics responded to the Palmdale home, Gabriel was unresponsive. The boy, who had a fractured skull, missing teeth and cuts and bruises dotting his body, later died at a hospital.

In a dissenting opinion, one of the justices wrote that she was “disturbed by the negative incentives this case creates for social workers and for DCFS,” saying she believes it strips away incentive for social workers to want “to reform and repair the parts of the system that may fail the children it is intended to protect.”

“We have, in effect, encouraged DCFS and its social workers,” she wrote, “to cover their tracks if they stumble on the cracks in the system.”

Attorneys for the social workers, however, praised the ruling as a necessary course correction.

Clement’s attorney, Shelly Barbara Albert, said the process has been extremely stressful for her client.

“She’s looking forward to putting this behind her,” Albert said.

Lance Michael Filer, who represents Rodriguez, said that his client had been waiting for this news for a long time.

“Our position has always been the same,” Filer said, “that neither she nor anyone else in her shoes should have been held criminally accountable for the unpredictable nature of criminals, and that the people that actually harmed Gabriel have already had their trial and day in court.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.