Skeletal remains of Japanese American incarcerated at Manzanar found in mountains

In the treeless, boulder-strewn Williamson Bowl near California’s second-tallest mountain, Giichi Matsumura stopped to paint.

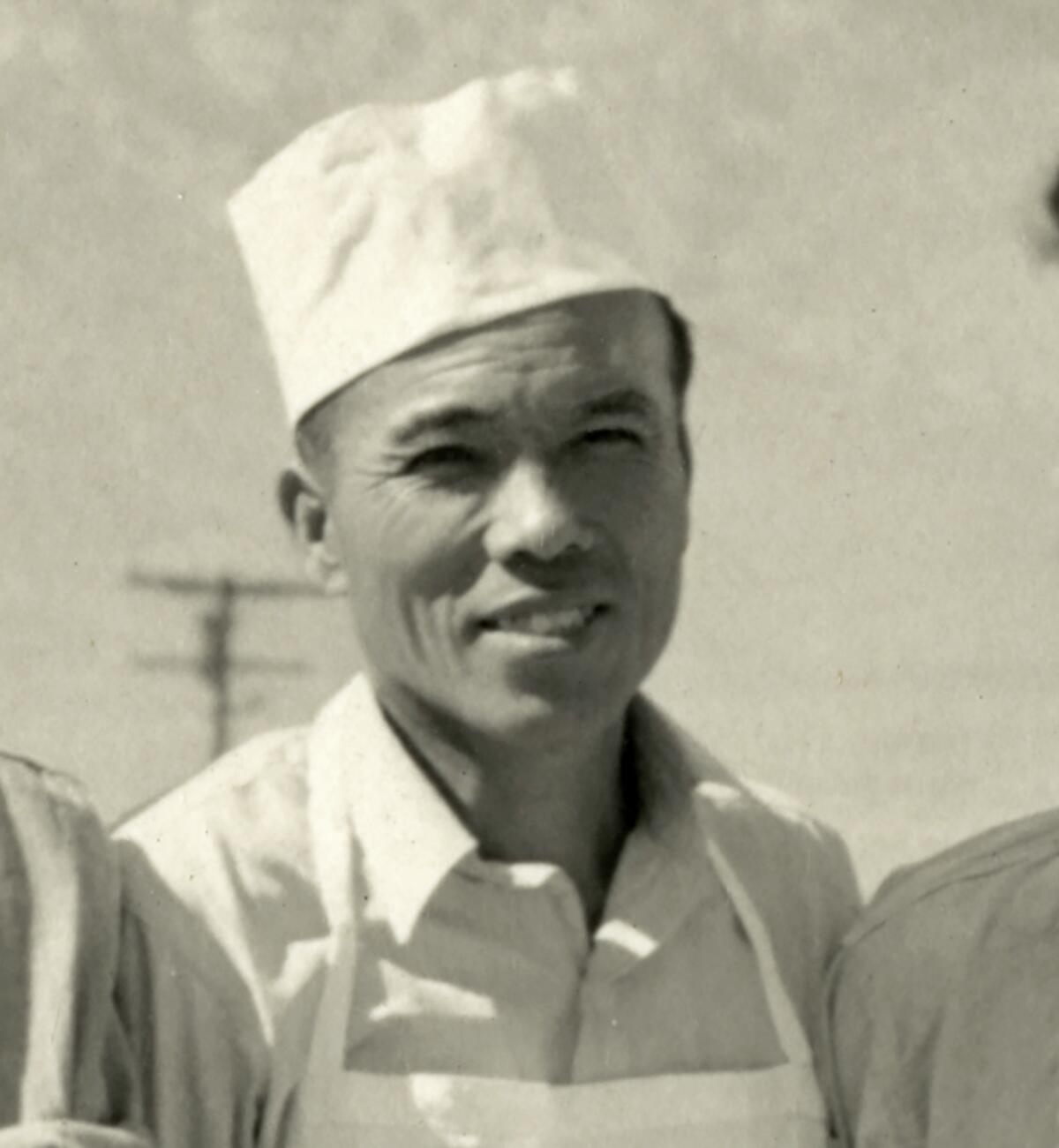

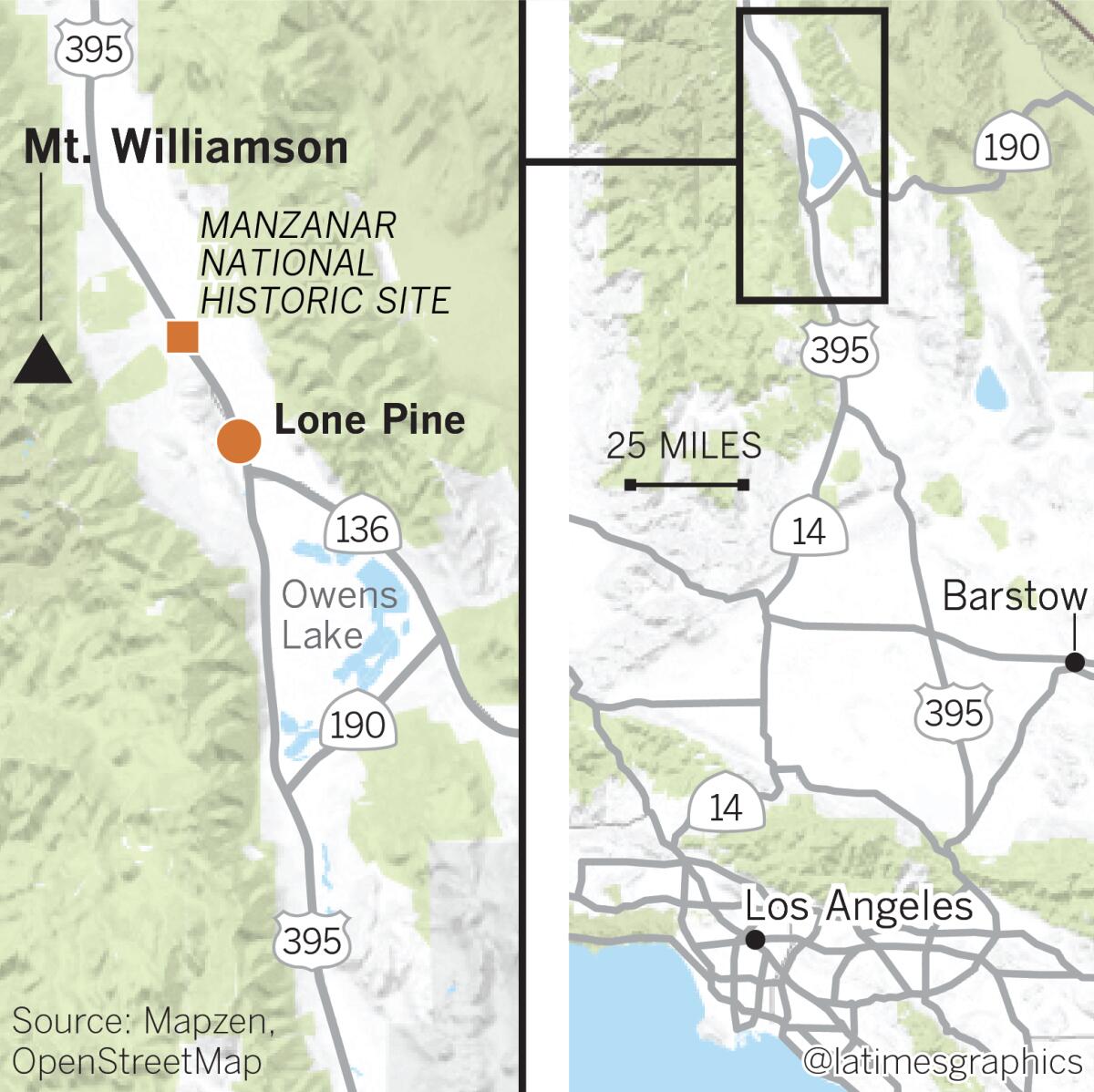

It was Aug. 2, 1945, in the waning days of World War II. The 46-year-old Japanese American man from Santa Monica had been incarcerated with his family for three years at the Manzanar War Relocation Center and had set out with a group of men who left camp to go fishing near Mt. Williamson, 14,380 feet above sea level.

When Matsumura stopped, the group kept moving. But a freak summer blizzard moved in. The fishermen hid in a cave, hoping Matsumura had returned to camp. He had not.

His body, found by hikers a month later, was buried beneath a pile of rocks. He was memorialized in a Buddhist ceremony at Manzanar. His widow never could reach the grave.

For 74 years, the grave was lost to time and elevation. Like so much from the closing days of the war, it became a fading memory held by aging survivors of the camp who rarely spoke of the tragedies they endured.

Last week, the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office and the National Park Service announced that they had used DNA to positively identify Matsumura’s body, which was found by hikers in October.

Authorities retrieved his skeleton this fall by helicopter, and an official with the Inyo County coroner’s office said on Saturday that authorities are hoping to meet soon with his family and return the body.

“We were pretty shocked to hear that his grave had been rediscovered,” said Bernadette Johnson, superintendent of the Manzanar National Historic Site. “It is extremely hard to reach.”

Japanese doctors were blocked when they tried to open a hospital in the 1920s. They eventually took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court — and won.

Matsumura’s death and the loss of his grave for so many years is one of the enduring tragedies of the U.S. government’s incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent — two-thirds of whom were, like him, American citizens.

“I think we try to focus so much on the success stories, that, despite this horrible thing happening to them, this community was resilient; it was able to recover,” said Emily Anderson, project curator for the Japanese American National Museum.

“But the flip side to that story is there were a lot of people who didn’t make it out, who were devastated because they were traumatized. They endured systemic racism and injustice. To expect a group to survive resiliently, unscathed, is unreasonable.”

For each individual family who experienced a death during the incarceration, “that loss was immeasurable,” she said.

Matsumura’s daughter, Kazue, was 10 when her father disappeared. In a 2018 oral history for the National Park Service, she said her mother was terrified to suddenly be alone, in her 40s, with four children.

She stopped eating. And when they couldn’t find him, “she had black hair, and it turned white all of a sudden,” Kazue Matsumura told interviewers.

Matsumura’s body was found by a lake in Williamson Bowl for the first time on Sept. 3, 1945, by a couple from nearby Independence, according to the National Park Service. A party of six hiked to the area to bury him. Ito Matsumura sent a sheet to cover her husband’s body.

The Buddhist Church held a funeral for Matsumura at Manzanar, and his family left camp a month later to return to Santa Monica, where they had lived before their forced eviction in 1942, authorities said. Her mother worked two or three jobs at a time to feed her children, Kazue Matsumura told the Park Service.

At the widow’s request, the family returned to Manzanar several times after the war. They grieved not being able to visit Matsumura’s grave.

“That was very hard, because it’s so high and we can’t get up there,” Kazue Matsumura said. “And to this day, it seems like he’s not passed away. It seems like he’s gone someplace because I didn’t see his body.”

Ito Matsumura, the widow, was 102 when she died in 2005. Her headstone in Woodlawn Cemetery in Santa Monica includes Giichi’s name.

Cory Shiozaki, a documentarian whose 2012 film “The Manzanar Fishing Club” told the story of prisoners who escaped the camp at night to climb into the Sierra Nevada to fish for trout, said Matsumura had begged to tag along with the fishing group.

The anglers — led by Amos Hashimoto, who had lived in the Japanese fishing village on Terminal Island — knew the war was winding down and wanted to take one last fishing trip to the far side of Mt. Williamson. Initially, they didn’t want Matsumura, who was much more skilled at watercolor painting than fishing, to join, Shiozaki said.

“Amos kind of looked at him and felt he wasn’t in very good physical condition to make this very difficult hike,” Shiozaki said. “They had to enter a 12,000-foot passage, Shepherd’s Pass. ... But he was so persistent, finally Amos relented and allowed him to join.”

Fishermen had been venturing out of the camp for years, Shiozaki said. When it opened in 1942, security was heavy, with armed guards in towers with machine guns and searchlights.

“But yet, there were incarcerees who said, ‘I need to get out of this place to feel whole again,’” Shiozaki said. They would sneak out, “kind of like in ‘Hogan’s Heroes,’ and wait until the moment the searchlight passed and sneak under the barbed-wire fences.”

Sometimes they took their tackle and bait. As they climbed, they found tree branches to fashion into poles.

Within a year and a half, Shiozaki said, security was relaxed. The armed guards were removed.

By the time Matsumura and his party set out, the government’s exclusion order had been lifted and people were able to leave the camp, which closed later that year. But like other families incarcerated during the war who had no home or business to return to, the Matsumuras continued living at Manzanar.

On the mountain, besieged by the sudden snowstorm, the fishermen took refuge in a small cave, hoping Matsumura made it back to camp. They organized several search parties.

During one search, they found a sweater. His wife confirmed it was his.

When the hikers from Independence passed through a month later, they noticed a branch protruding from some rocks, which seemed strange since they were above the tree line, Shiozaki said. There, they found Matsumura’s decaying remains.

“The fishing party became the search party. The search party became the burial party,” Shiozaki said.

They fashioned a rock cairn, left a Japanese epitaph, and took hair and nail clippings from Matsumura’s body to return to his wife, the filmmaker said.

Shiozaki, 70, of Gardena, made his film because so many people outside the West Coast have never heard of the incarcerations. His own parents were Nisei — the children of Japanese immigrants — and, like many others, didn’t speak about their imprisonment for decades.

His mother was sent to a camp in Utah. His father was sent to Idaho. Shiozaki learned about the incarcerations in a college history class.

“I was clueless until I was in college,” Shiozaki said. “They never talked about it. I was very adamant and confronted my dad and said this was horrible. That set me on the path to become a filmmaker. .... Things like this shouldn’t ever happen again.”

Shiozaki also happens to be a licensed fishing guide in the Eastern Sierra. He began his film about the fishermen of Manzanar after seeing a portrait of an internee holding a string of six golden trout — which he recognized as specimens from high-altitude lakes.

Anderson, from the Japanese American National Museum, said there is a growing urgency to telling stories like those of the fishermen and Matsumura as the number of aging survivors of the camps dwindles.

She hopes that people who learn about him will research this dark chapter of American history, which too often is forgotten, she said.

“I hope people will take this not as an idiosyncratic, romantic story,” she said, “but as an opportunity to understand the broader historical context.

“We see the relevance and importance of this story not just because something bad happened to them, but because their constitutional rights were violated and that’s something that could happen to any marginalized group.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.