Lead paint, banned for decades, still makes thousands of L.A. County kids sick

During his pediatrics residency training at a hospital in Hollywood, Dr. David Bolour rarely gave a second thought to lead poisoning.

Lead paint had been banned since before the 36-year-old doctor was born. Children being harmed by the once-ubiquitous metal was a thing of the past, he thought.

But when he started as a pediatrician in 2015 at St. John’s Well Child and Family Center in South Los Angeles, Bolour began testing every child who came in for lead poisoning. And he learned that about 1 out of 100 had elevated lead levels, he said.

Public health officials consider even low levels of lead found in a child’s blood to be lead poisoning, since studies have linked just small amounts of lead exposure to irreversible brain damage and stunted development in kids.

“When I came here, I realized this is a real problem,” Bolour said.

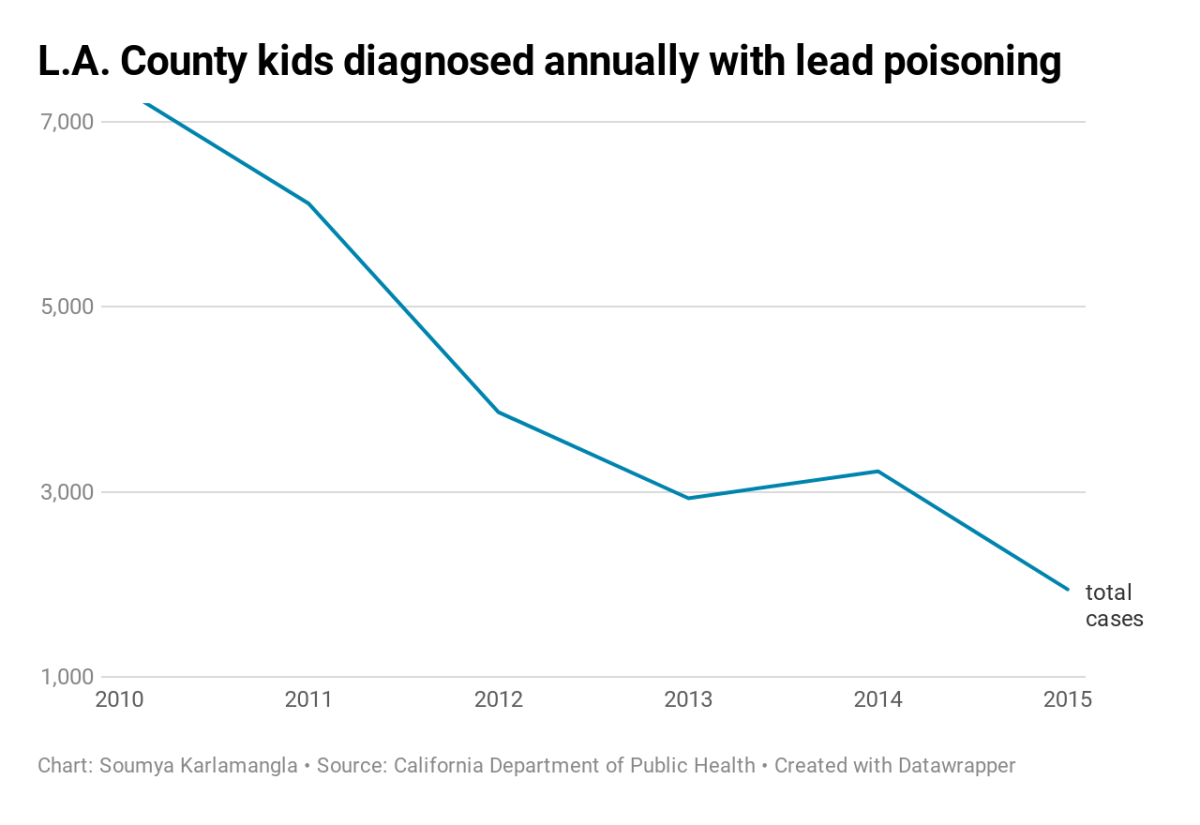

Although lead poisoning has become less common in recent years, roughly 2,000 children are diagnosed with unsafe levels of lead in their blood each year in Los Angeles County, according to state data. South L.A. is one of the most affected areas.

Parents who learn their children are being exposed to lead usually require improvements in their home to make it safer. Stopping the lead exposure will bring down a child’s blood lead levels.

But until their children are tested, families are often unaware their homes could be a source of lead, Bolour said. Upon asking them about their living conditions, Bolour frequently learns that their old homes have not been renovated, and are likely coated in lead paint.

Young children are usually afflicted by eating paint that has chipped off the walls or ingesting paint dust that contains lead. Lead-based paint was banned in 1978, but most homes in L.A. County were built before that, so many children are at risk just from crawling around their living rooms or playing in the yard.

“When it comes to lead poisoning, it’s still the most important pediatric environmental problem in the United States,” said Dr. Cyrus Rangan, medical toxicologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Over the next seven years, L.A. County will receive $134 million to eliminate lead hazards in homes as part of a settlement with three paint companies that were once major suppliers of lead paint. But the payout will cover only a fraction of the work that is needed, officials say.

The settlement money can be used on any of the 720,000 homes in the county built before 1951, when lead concentrations in paint were highest. But officials say the funds will pay for remediation for only about 5,000 units, leaving thousands still in need of repair.

When a child comes into St. John’s clinic for a checkup, Bolour administers a finger prick test to check lead levels.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises doctors to pay attention to a lead blood level higher than 5 micrograms per deciliter. The vast majority of children with lead poisoning don’t show any symptoms, but even low levels of lead exposure have been shown to permanently affect IQ, the ability to pay attention and academic achievement, according to the CDC.

The children most affected are those who are just learning to crawl or walk and are exploring their lead-laden environment.

“When they test positive, I ask the parents, ‘How’s the housing? Is there chipping paint?’” Bolour said.

Paola Mejia’s son Byron was a year and a half old when a blood test at St. John’s revealed a lead level of 21 micrograms per deciliter.

Later, a health department inspector found lead in the paint in Mejia’s 1928 South L.A. house, as well as in the soil outside, she said. After the doctors explained the dangerous effects of lead, Mejia began watching her toddler constantly, afraid he would ingest even more of the substance.

“I was so nervous, following my son everywhere,” she said.

The damage from lead poisoning is irreversible — there is no treatment other than reducing further exposure, experts say. The CDC says that lead levels of 5 micrograms and over per deciliter are unsafe for children, but that designation is somewhat arbitrary, said Dr. Aparna Bole, chairwoman of the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Environmental Health.

“The only normal level of lead is zero,” Bole said.

However, it is impossible to tease out what problems are due to lead alone since many factors affect children’s brains, Bole said. Possible deficits caused by lead can be offset by things that help development, such as a diet of healthy foods, a stable housing situation and high-quality preschool, she said.

But three years after the initial diagnosis, Mejia still worries that the lead caused permanent brain damage.

Byron had to begin seeing a speech therapist because he didn’t start to talk until after most children, she said. And sometimes he gets very angry, which Mejia fears is a behavioral problem caused by the lead exposure.

“The only thing I want for my two kids is that they’re healthy. ... I want good things for them,” said Mejia, 30. “So it made my husband and I very concerned that lead was going to his brain.”

L.A. County plans to begin its lead remediation project in early 2020, said Janet Scully, who oversees L.A. County health department’s lead abatement program.

The funding is the product of a suit filed in 2000 by several local governments, including L.A. County, against the paint industry, alleging the companies promoted lead-based paint even though its dangers have been known as early as the 1890s. L.A. County is receiving nearly half of the $305-million payout from ConAgra, NL Industries, and Sherwin-Williams Co.

The first step, Scully said, will be testing homes for lead hazards to see which are the most dangerous. In L.A. County, between 25% and 40% of old homes that are tested for lead don’t actually come back positive for lead, she said.

Once dangerous homes are identified, county workers will inspect affected homes for the biggest hazards — typically doors and windows where friction and regular use cause paint to flake off. Instead of totally repainting the house, workers will paint over problem areas or try other ways to mitigate lead hazards, she said.

Still, the average cost of remediating a home, which sometimes includes temporary relocation for a family while the work is being done, is $14,000, she said.

“Even though $134 million sounds like a lot of money, it’s expensive to do this kind of hazard remediation,” Scully said.

Three years ago, Williephine Mohead’s daughter Gracie, then 2, was diagnosed with lead in her blood. At one point, her blood lead levels were 27 micrograms per deciliter, Mohead said.

When Mohead learned how lead was affecting her daughter, she immediately moved out of their South L.A. apartment. Inspectors eventually came and tested her home for lead, she said.

“It was throughout the house: It was the paint, it was in the carpet, it was in the soil, it was in my water,” she said.

Unfortunately, children often act as lead detectors, since their small bodies absorb the chemical and notify families of the risk through testing, experts say.

But across the state, not enough children are being tested for lead exposure, said Susan Little, senior advocate for California government affairs for the advocacy organization the Environmental Working Group.

All children with Medi-Cal, the state’s version of low-income health insurance, are required to have their lead levels checked at their 1-year-old and 2-year-old checkups. But in 2016, fewer than 30% got the testing, according to an analysis by the environmental group.

That means many children are probably going undiagnosed, and their homes unfixed.

“It is so insidious,” Little said. “Its effects can be largely hazardous, especially when people are unknowingly being exposed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.