The salt shaker teetering on a pot lid on his naked back could not fall.

Victor Hayes kept his face pressed into his mattress. The gunman promised to kill him if he heard the objects slip.

Until that moment, pinned by kitchenware, Hayes embodied all the swagger of the 1970s American male.

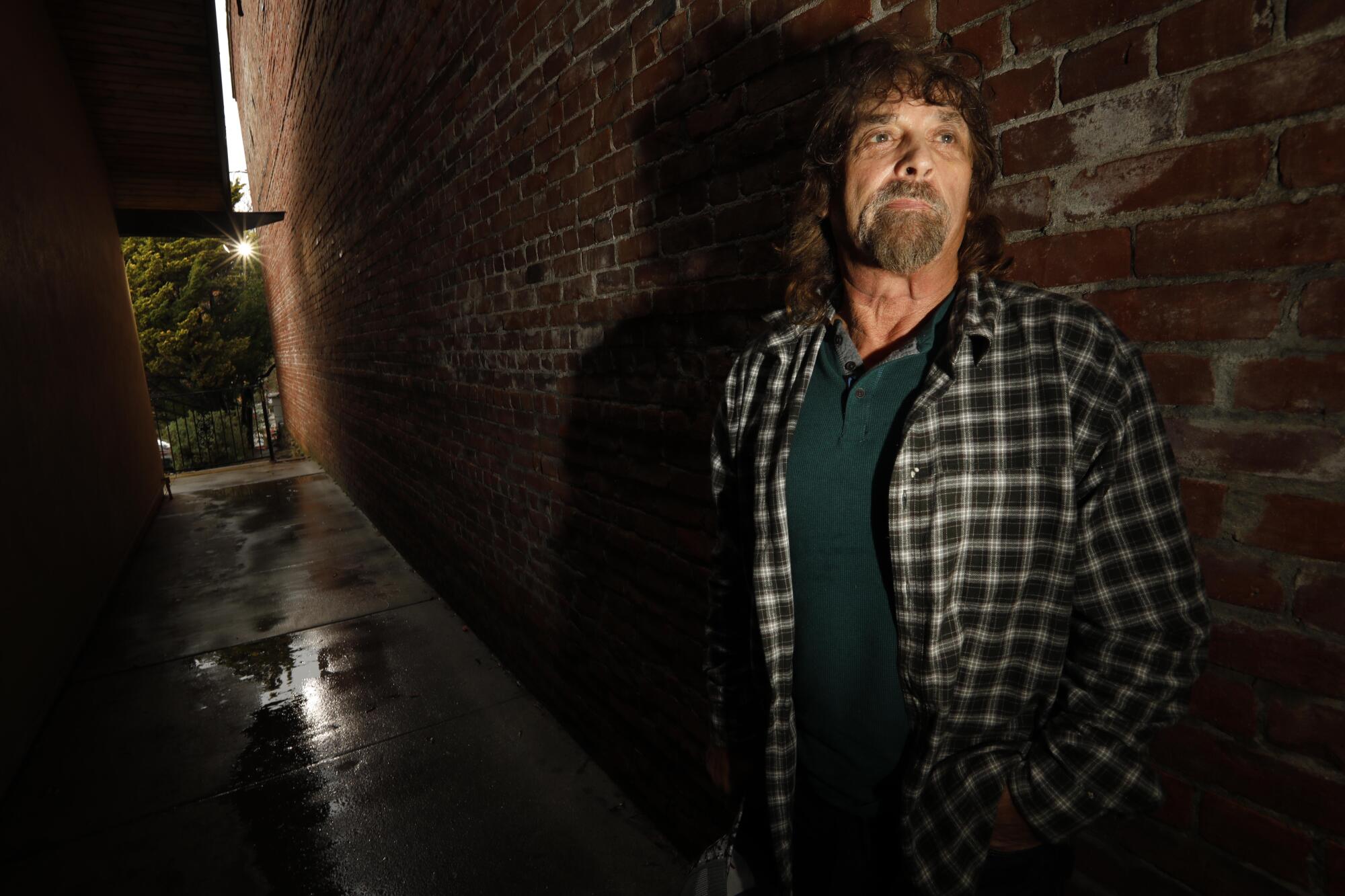

He was 21, with the long thick hair and heavy mustache of a rocker, a souped-up Chevelle in the garage, and a custom chopper parked in the living room like something off the set of “Easy Rider.”

Hayes protected his property with similar machismo — a pit bull in the backyard, guns in the house. His girlfriend slept against the wall, and Hayes took the outside of the bed because “I’m the man.”

But just after midnight on Oct. 1, 1977, an intruder blinded Hayes with a flashlight and held a gun on him as he removed Hayes’ rifle by the headboard. There was no time for Hayes to go for the .22-caliber Magnum. The single-action revolver stayed beneath the mattress and box spring just inches away.

He was rolled over in bed, his ankles and wrists bound with shoelaces. Then the intruder perched a metal lid and a salt shaker on Hayes’ naked back, and said if he heard them fall, he would “blow his f------ head off.”

Hayes was reduced to paralysis while the man in the living room raped his 17-year-old girlfriend.

It was clear this was more than a sexual assault.

Eight times in the next hour, the rapist returned to the bedroom. He stood over Hayes, sucking in air between clenched teeth as if in pain. He taunted him, holding a gun so close that Hayes could hear the cylinder roll as the rapist pulled back the hammer.

He whispered into Hayes’ ear.

“Sharon is next.”

His mother’s name.

::

The Golden State Killer’s violence against women has been retold in all its terrible details. In hundreds of crimes that spanned 11 counties from the 1970s to 1980s, he escalated from window peeking to stalking, rape and serial murder. Thirteen people were bludgeoned or shot to death, more than 50 women and girls were sexually assaulted.

The women were victims as well of the times, contending with the social stigmas of rape, family members who tried to cover up the harm, and police who echoed rape’s lesser status as a crime by describing the rapist’s repeated sexual assaults as “gentle.” The California Legislature at the time did not classify rape as a great bodily harm.

But the attacker had male victims as well — 29 men and boys bound up and threatened with death who were forced to witness the terror of their loved ones. These were victims that the police rarely mention and even they themselves and their families have trouble acknowledging.

He was called by many names. Eventually, he would become one of California’s most deadly serial killers.

Crime scene reports and interviews show investigators focused their inquiries, emotional support and the investigation itself on the women.

They show little contact with male victims beyond their initial statements. One officer in Contra Costa County in his report repeatedly referred to the man bound and taunted at gunpoint as a “witness.” The only two male victims willing today to talk about the experience told The Times they felt treated like bystanders. One of them described the sudden shift in police demeanor after his traumatized partner was driven away to the hospital. He walked back in to find crime scene technicians dusting for fingerprints, oblivious to him and laughing at some shared joke.

All of those male victims refused early efforts by a Sacramento County detective to start a support group, and over the next 40 years, disappeared into the shadows. After the surprise 2018 arrest of a suspect based on DNA matches, only two men stepped into public view. Even if the cases go to trial, they will remain bystanders: There are no charges pending related to the crimes against them.

But the arrest of Joseph DeAngelo — a former police officer with a reputation for aggressive challenges against men — brings into focus the calculated emasculation of male victims.

There was no question to Victor Hayes that he was as much a target of the masked man in a leather jacket standing over him as was his girlfriend.

“There was a lot of testosterone going on, an alpha male type thing,” Hayes said.

Hayes felt it not just in the taunting as he lay immobilized, but the small actions, like the half-eaten pie — a lemon meringue he had bought the night before — that the rapist left on the seat of Hayes’ chrome-and-steel motorcycle. “It was like I see your s--- ... but I dominate you.”

The young man’s first desire was for violent revenge. It was still dark when police left. Hayes considered the wreckage around him and cried.

Then he began to laugh. A thought had entered his mind — illogical but he seized on it. Hayes unlocked the sliding back door, gathered and loaded his guns. Then he crouched in the dark on the kitchen floor in wait.

He prayed. “Come back. Come back.”

The rising sun and realization there would be no second chance brought Hayes into another minefield common to the male survivors: a pressing need to apologize.

Bob Hardwick would seem to share little with Victor Hayes. He was 29, a divorce lawyer living in Stockton when he and the woman he would soon marry became victims of the 31st attack.

Hardwick knew he had no chance against the man holding the couple at gunpoint. A misstep could have ended in their deaths — as it did for five couples the rapist attacked. Still there was that disturbing question of whether Hardwick could have protected Gay.

“I was the same way as any other men, that Gay was the real, the real victim,” Hardwick said. “I felt bad that I couldn’t do anything about it.”

Afterward, Gay struggled with the trauma through counseling and a career change.

Hardwick busied himself in his law practice and immersed himself in sports, playing on softball leagues, golfing and skiing.

And anger, almost the only emotion sociologists say society permits men in trauma, flamed.

Hardwick, a man so soft-spoken that listeners have to lean forward, became reactive to any trespass of his personal boundaries.

Hoodlums urinated on his lawn, so he grabbed his gun and he shot out the tire on their car. He ran into one of the troublemakers at the grocery and threw the kid against a plate glass window. Even in the controlled environment of court mediation, Hardwick dealt with the obnoxious client of another lawyer by pinning the man to the wall by his throat.

Only when Gay, increasingly isolated, threatened to leave did they confront the stress drowning them both. A marriage counselor suggested divorce, the path chosen by more than half of the couples attacked by the rapist.

Hardwick and Gay left her office and went to dinner, and at the table, decided to fight for a future together.

The serial rapist’s first victims were solitary women and girls. But within a year, the attacks focused on couples. And those attacks were increasingly aimed at men of higher social statures — medical professionals, lawyers, military officers, teachers and business owners.

“He didn’t just walk in and say, ‘Hey, there’s two people here,’” said forensic profiler Leslie D’Ambrosia, brought in on the unsolved bedroom murders in the 1980s. “He wanted there to be two people there because that was his intent, to degrade and to emasculate.”

In some attacks, investigators believe the men were the primary target. One case included a construction boss who arrived at work six months later to find the same sort of strings used to bind him and his wife left on the seat of his work machine.

“He was just such a revolting sense of power,” one male victim told police, describing how over and over again, the rapist played with a gun at his head, cocking and releasing the hammer. He whispered, “You don’t like this, do you?”

Masculinity, especially under the societal norms prevalent during the 1970s, is often measured by the ability of men to protect women. Forcing a man to witness the rape of his wife is an incalculable blow to male ego.

“There’s very little that I can think of that would be more an intentional stealing of somebody’s honor,” said Donald Saucier, a Kansas State University scholar who has spent a career leading studies on aggression and male behavior.

Twenty-one couples were attacked before the increasingly unstable rapist began to lose control of the men. Two couples escaped. Another man broke free of his bindings and turned on the attacker. At that point the rapist began to kill his victims.

Living through the night was only the start of survival.

Some of the raped women said their husbands and fathers were unable to accept their enduring pain and they suffered further.

More From This Series

One man burned his wife’s nightgown as if to erase the event. Another man moved his family out of town and forbade his daughter from mentioning her rape, even to other family members. When a detective attempted to start a support group for the male victims, not one showed. Male victims remained shadowed through the next 40 years as the unsolved case grew in notoriety, attracting books, podcasts and television series.

Hayes never married and lives alone in the woods, deer trophies on the cabin walls, cutting firewood for a living.

When DeAngelo was arrested, Hayes was the only male victim of the Golden State Killer who came to court. The California Legislature set aside special funds for victims of the four-decade-old crimes, but only two men applied — Hardwick and Hayes not among them. The money is primarily used for trauma counseling.

“They don’t see [their experience] as trauma. They see it as failure,” said male trauma specialist Dan Griffin, author of such books as “The Man Rules.”

“Men aren’t going to get help for that.”

Hardwick insists he needs no guidance.

“I went through trauma. I’m sure I’m probably still going through trauma. But I’m not going to let it affect me,” he said.

But if he ever does enter the therapy room, he said it will be to support Gay.

::

DeAngelo had many of the same masculine trappings as Hayes ... guns for hunting, a motorcycle, a muscle car. But the image of authority he cultivated in his first job as a small-town police officer took a heavy blow with his transfer to the larger force in Auburn.

As a cop in Auburn, DeAngelo floated through eight-hour patrols of the community, pulling relief shifts for other officers, bouncing from false alarms to petty thefts and town drunks.

Sometimes he responded to calls with similarities to the stalking patterns of the East Area Rapist 30 miles south. On one afternoon in October 1976, DeAngelo took reports from a woman who said someone tried to break in through her bedroom window and from two other women who received obscene calls. DeAngelo wrote that one of the women called her harasser’s voice “pleasant,” but she “just didn’t like what he said.”

More than once, an Auburn resident complained about DeAngelo’s confrontational attitude. Such stories were repeated by family members who called him quarrelsome and superior, neighbors with tales of explosive confrontations, and a young man whose car changed lanes in DeAngelo’s path.

DeAngelo followed the driver into a parking lot and jumped from his truck shouting obscenities.

“Maybe this guy felt like we cut him off, I don’t know,” said Alan Malbouvier, who was with his mother and a friend from France. “He came out screaming at us. ... F this and F that.”

Malbouvier and his mother backed off, but his friend, a former handball player, confronted DeAngelo and the two collided and knocked heads.

When the men split, there was blood on DeAngelo’s face. DeAngelo sued the Frenchman and received a $15,000 settlement for dental work and lost income, though by then, 1983, he had been fired from policing for shoplifting a hammer and was seeking state money for vocational retraining. The Golden State Killer by that day had killed 12 people.

Control remains a central fact of DeAngelo’s now-limited life, housed in solitary confinement on the top floor of the Sacramento County Jail. He has not entered a plea — nor have prosecutors presented their evidence to bind the case over to trial.

He is locked in his concrete room almost 23 hours a day. Inmates say DeAngelo refuses food and in 18 months has dropped from 205 pounds at arrest to an estimated 135 pounds at his last court hearing in August.

The sheriff’s office, county prosecutor and public defenders representing him would not comment on DeAngelo’s condition.

The possibility that DeAngelo, now 74, could die before trial leaves victims and police conflicted.

Some case investigators say they would be satisfied to see it end there. Bob Hardwick said a trial doesn’t matter to him, but his wife wants a reckoning. For Victor Hayes, a trial could deliver revelations that go beyond whether DeAngelo is guilty.

He has wrestled with isolation and anger since the moment detectives walked out the door the morning of the attack. “My head is, like, racing and I’m thinking, ‘You’re not going to, like, take me down to the station to, like, talk to me some more? Give me a cup of coffee? Offer me another cigarette?’”

His father, a corrections officer, took news of the attack with a look that told Hayes he thought his son had fabricated the story. “I don’t think my dad ever asked me how I was. He definitely didn’t ask how my girlfriend was,” Hayes said.

And when his father had him recount salacious details of the assault for his work buddies — could he hear his girlfriend and the rapist in the next room? — for the seeming thrill it gave them, Hayes stopped talking.

The morning after the attack, Hayes felt a duty to go to his girlfriend’s mother.

“I just said over and over and over, ‘I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.’”

She said, “It’s not your fault. Don’t blame yourself.”

“And I said, ‘But it is, because I shouldn’t allow this to happen.’ And I was angry ... my adrenaline was going, and I was ready to fight right then and there. But who am I going to fight when there wasn’t anybody there?”

In time, that rage turned into a determination to find someone to take responsibility. Without a trial, Hayes fears he will never learn who that is. And in the nearly two-year absence of information since DeAngelo’s arrest, his mind builds conspiracies: Hayes fears he will never learn how someone, especially an officer of the law with a wife and children, could disappear to prowl so extensively without notice.

Internal records show the Auburn Police Department spent seven days immediately after DeAngelo’s arrest attempting to go through the former officer’s duty logs and old rape and prowler reports, looking for connections. Then the investigation was halted. A lieutenant said most crimes they might uncover would be so old they could no longer be prosecuted anyway.

“I am telling you that something is very, very, very wrong in this case,” Hayes said. “Very wrong.”

He is still gripped by the attack 42 years ago. He trembles as he calls forth the image of the man standing over him. Increasingly, he said it looks like a policeman: his dark work slacks, the bluing on his revolver, the way the intruder held the silver flashlight over his shoulder.

In the widening circle of his unmet anger, Hayes wants to know who enabled this man.

“I want somebody to be held accountable.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.