The sea wanted to take this California lighthouse. Now, it’s part of a conflict between a town and two tribes

TRINIDAD, Calif. — It stood like a pretty sea siren atop the coastal bluff overlooking the rocky outcrops of Trinidad Bay.

The cheery little lighthouse, with its cherry-red roof and bright white walls, beckoned countless painters and photographers. It was such a mainstay in Trinidad that its image is included in the city’s logo.

Then the ground began to crumble. Rain moved the earth. The bluff cracked, a sidewalk warped, and thus ended the charmed life of the Trinidad Memorial Lighthouse, which suddenly threatened to slide into the Pacific.

What followed was a drama in this Humboldt County hamlet, population 360, involving two Native American tribes, a women’s civic club and existential questions about California’s storied coastline and the forces of climate change.

In its own humble way, the lighthouse — which was moved, at least temporarily, to a harbor parking lot — stands as a harbinger of conflicts to come in the Golden State, where coastal land is being lost to a rising and warming ocean and eroding coastal cliffs are increasingly likely to fail. Seaside communities hoping to save their infrastructure have been left to debate options such as building sea walls, adding sand to disappearing beaches or opting for managed retreat — pushing buildings back from the water’s edge.

“The coast in California is falling apart,” said Jennifer Savage, policy manager for the Surfrider Foundation, a coastal protection group. “It’s flooding. I think we will see more structures being relocated from dangerous locations because we will see more dangerous locations up and down the coast.”

Here in Trinidad, hard feelings linger over the lighthouse move.

“It was a nightmare for our community, and we’re still sort of going through PTSD over it,” said Patti Fleschner, a longtime member of the Trinidad Civic Club, the century-old women’s philanthropic group that owns the lighthouse. “But we’re moving on because that’s what we do.”

In the winter of 2016-17, California swung from extreme drought to deluge. That winter brought wildflower superblooms to the Anza-Borrego desert near the Mexican border, epic snowfall in the Sierra Nevada and a landslide that buried Highway 1 near Big Sur.

In Trinidad, the rain triggered a long-dormant landslide, opening fissures in the grass-covered bluff beneath the lighthouse. Like much of the California coast, the site sits atop a highly erodible bedrock called Franciscan Complex, which essentially is a mix of hardened mud, clay and sand interspersed with harder blocks of rock.

The active landslide also threatens Edwards Street, a main thoroughfare in Trinidad behind the bluff, according to a geological report commissioned by the city.

The small hilltop parcel where the lighthouse stood is owned by the Civic Club. In 1949, the club built the Memorial Lighthouse, a concrete replica of the still-functioning Trinidad Head Lighthouse that has stood on a nearby rock promontory since 1871.

The Memorial Lighthouse was built to display the original fourth-order Fresnel lens — the intricately layered glass prism that sent magnified light from a coal-oil lamp across the waves — removed from the Trinidad Head Lighthouse after it got an electric beacon.

The Memorial Lighthouse eventually became a tribute to more than 240 people whose names are inscribed on a marble slab engraved with sea gulls and on plaques affixed to the lighthouse and a concrete retaining wall on the bluff.

After fissures appeared, geologists warned city officials that attempts to permanently stabilize the top of the bluff would, essentially, prove futile.

The Trinidad Civic Club, armed in December 2017 with an emergency coastal development permit from the city, planned to scoot the lighthouse back 20 feet on the bluff to what geologists said was more stable ground.

But the bluff is the site of an ancient Yurok tribal village called Tsurai and, according to the tribe, contains burial grounds. Just before the lighthouse was to be moved back, tribal members climbed onto its roof with a banner reading #AllGravesMatter. On the ground, scores of people held hand-made signs: “Native rights,” read one. “The replica lighthouse is not historical!” read another.

They demanded that the structure be removed entirely from the bluff.

“Those aren’t just any graves. Those are our family and our fellow village members,” said Sarah Lindgren-Akana, secretary of the Tsurai Ancestral Society, a nonprofit composed of lineal descendants of the village. “These aren’t unknown people.”

The Memorial Lighthouse, the tribe said in a statement, stood on a site whose cemetery “is occupied, in part, by Yuroks who were killed by white settlers during the Gold Rush.”

“For Yuroks, the Trinidad Memorial Lighthouse is a monument to this tragic era. We feel like it is no different than the statues created to honor Confederate soldiers in the South,” said Yurok Tribe Vice Chairman Frankie Myers. “What we’re asking is for the city and Civic Club to give the same respect to our ancestors as they give to the families of the .... people who were buried at sea.”

By 1850, white settlers had claimed the site of Tsurai. The land eventually was purchased by a lumber company, according to the Tsurai Management Plan, an agreement by tribal members, the city and the state Coastal Conservancy to try to resolve conflicts over the land.

The last villager of Tsurai left her ancestral home in 1916 after the site’s water source was contaminated by garbage dumped off the bluff.

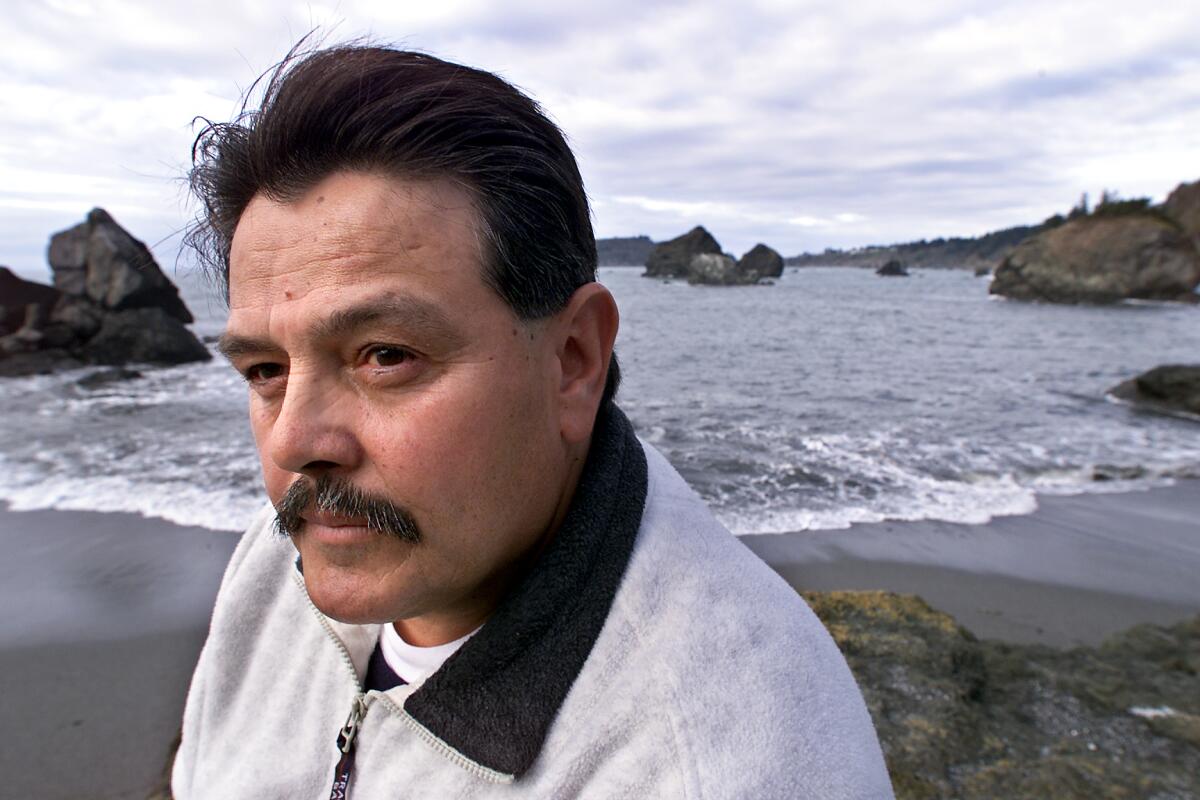

For 69-year-old Axel Lindgren III and his sister Kelly Lindgren, 58, the story of Tsurai is the story of their family.

Their grandfather was born there in 1890. Their great-grandmother was the last medicine woman of Tsurai. The Axel Lindgren Memorial Trail, a time-worn path from the top of the bluff down to the water, was traversed by generations of their family.

In the 1930s, amateur archaeologists excavated the last marked graves of Tsurai and left human remains strewn on the ground. The late Axel Lindgren II was walking to school one morning when he saw remains of people he knew, according to the Tsurai Management Plan. He later formed the Tsurai Ancestral Society to help protect the site.

“The city basically founded on top of us,” Kelly Lindgren said. “It’s amazing that we’re even still here, with what we’ve been through. For the city to continue this type of treatment of us — they’re still trying to get rid of us, but it’s in a different way.”

Sarah Lindgren-Akana, Axel III’s daughter, said the Ancestral Society has been warning the city for years that the bluff was failing and that development only sped up the natural process.

“They waited for it to become an emergency, and then they could go around the environmental impact report and all the studies,” she said.

As a result of the 12-day occupation of the Memorial Lighthouse, the city and the Civic Club scrapped the plan to move the structure back on the bluff, opting to relocate it.

In January 2018, the lighthouse was hoisted by crane and driven to the harbor parking lot at the end of Lighthouse Road. But that spot, directly on the sand, is owned by another tribe, the Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria. The federally recognized tribe was established in 1906 to house homeless California Indians from the Yurok, Wiyot and Tolowa tribes.

The land of the Trinidad Rancheria is within Yurok ancestral territory, which has long caused tensions between the two tribes. Currently, they are locked in a complicated fight, along with the city and the Tsurai Ancestral Society, over ownership of a 12.5-acre parcel of land surrounding the Tsurai village site.

The Rancheria owns the land around the harbor, including the pier and boat launch. The tribe is trying to place the land in a federal trust and wants to build a visitors center there — a plan that has outraged the Yurok Tribe, which says it’s just one more attempt to separate them from their ancestral land.

The Memorial Lighthouse now sits amid that conflict.

Jacque Hostler-Carmesin, chief executive officer of the Trinidad Rancheria, said her tribe wants to give the lighthouse a permanent home by the harbor. She described the Rancheria as “the problem solver, trying to eliminate a very contentious situation.”

“There are old feuds in the area,” she said. “I believe that the best solution was found. ... We believed that the families that have lost loved ones at sea deserve a nice memorial, and it really is the most appropriate place. The last thing I want to do is create more of a problem.”

But awkwardness remains in Trinidad, where the Lindgren family are well-known and respected. A traditional Yurok canoe carved by Axel Lindgren II is displayed in the Trinidad Museum. For years, he participated in Trinidad’s annual Thanksgiving Day blessing of the fishing fleet. Axel Lindgren III continues to do so.

Some residents blame younger members of the family for the lighthouse conflict, saying they got “too militant.” Many just don’t want to talk about it.

On a windy September morning, a small group of volunteers with the Trinidad Civic Club and the museum circled the lighthouse in its temporary spot, using brooms and spray hoses to clean sand and rust off its walls.

Mary Kline, 68, said her great-great-great grandfather homesteaded Patrick’s Point north of Trinidad in the 1870s, and her great-great grandfather came to the area about 1868.

The names of a lot of her friends and family buried at sea are inscribed on the memorial wall. A plaque affixed to the lighthouse itself has 14 names of people who died in the Pacific, including four Coast Guard members whose helicopter crashed during a rescue mission off Cape Mendocino in 1997.

The most recent name on the plaque is Sylvia Jane East, an 8-year-old girl swept out to sea in 2018 in nearby Big Lagoon.

“For a lot of these people who were cremated, or some of these whose bodies have never been recovered, this is like the family headstone,” Kline said. “It’s like going to a cemetery, and this is the only recognition some of these people ever have.”

As she spoke, the worst maritime tragedy in modern California history was on her mind: the burning and sinking of the Conception dive boat off the Channel Islands. She said she hoped the 34 people who perished there get their own memorial.

The lighthouse’s move has cost the Civic Club more than $80,000, Fleschner said. The 1871 Fresnel lens was dismantled and is sitting, in pieces, in her basement until a permanent position is decided.

As the lighthouse was being cleaned, Scott Baker, vice president of the Trinidad Museum Society, steered his aging GMC High Sierra past a locked gate and onto Trinidad Head promontory, where he helps maintain the old Trinidad Head Lighthouse.

Baker, 73, climbed into its belltower, contentedly silenced by the sight of the ocean on a clear day.

Baker grew up in Trinidad with Axel Lindgren III, a man he always liked. He’s still “a little miffed” about the whole fight.

“When I was a kid, everybody worked together on projects,” he said. “But now there’s so many egos involved. People can’t agree on anything.”

Here, Baker said, water is a big part of life, and death.

Fulfilling promises to his parents, he scattered his dad’s ashes off the Golden Gate Bridge and his mom’s off the Trinidad coast.

Their names are inscribed in the memorial on the bluff, where the Memorial Lighthouse once stood.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.