Dangerous L.A. apartment buildings most at risk in an earthquake are quickly being fixed

An earthquake safety revolution is spreading along the streets and back alleys of Los Angeles, as steel frames and strong walls appear inside the first-story parking garages of thousands of apartment buildings.

The construction is designed to fix one of the most dangerous earthquake risks: Wood apartment buildings collapsing because the skinny poles propping up parking at the ground level are not strong enough to withstand the shaking.

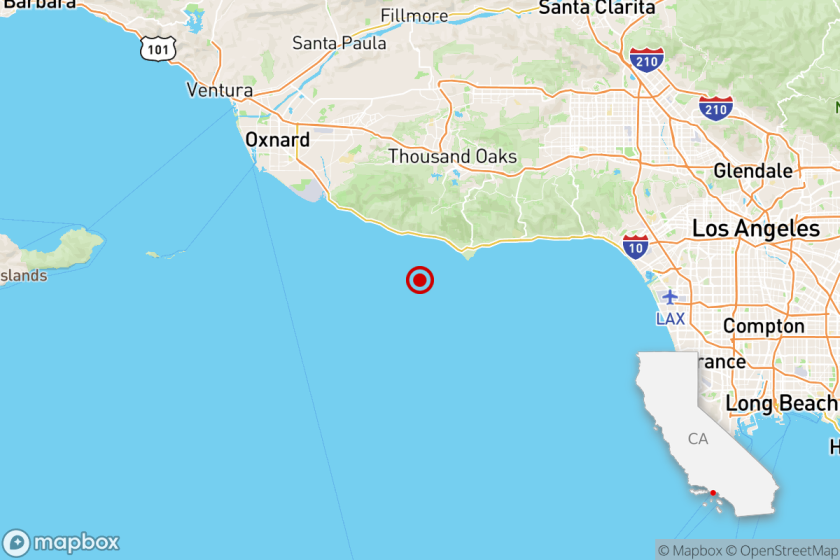

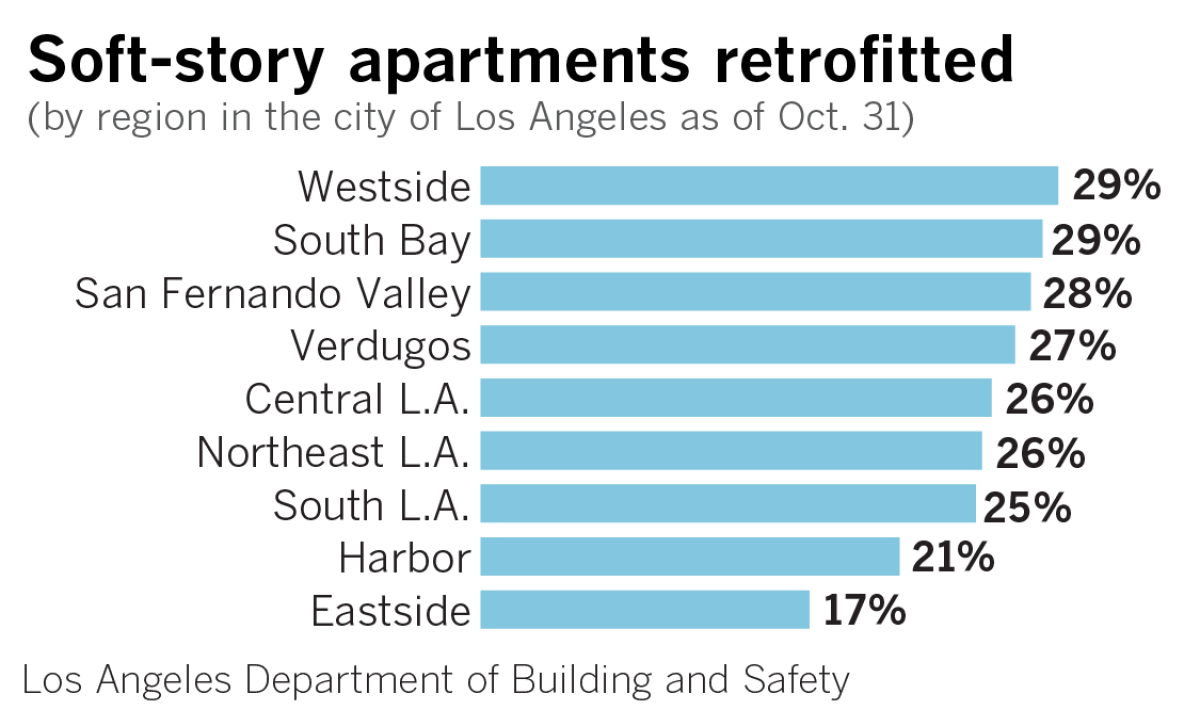

Now, 27% of Los Angeles’ 11,400 dangerous wood-frame apartments are retrofitted to better resist earthquakes, up from 5% just 14 months ago. Retrofit progress has been steady across the city, a Times analysis of city records shows. Among the regions with the most “soft-story” buildings, 29% of the apartments on the Westside and in the San Fernando Valley are retrofitted, and 26% have been completed in central L.A., which includes Hollywood, Mid-City and Koreatown. The Westside, Valley and central L.A. regions are home to more than 80% of the soft-story buildings in the city.

Only the Eastside lags substantially behind the rest of the city, with 17% of apartment buildings’ retrofit completed. But there are relatively few soft-story apartments there — fewer than 180.

There are still more than 8,000 soft-story apartment buildings that need to be retrofitted across the city.

The Times analysis found that some of the best progress for retrofits was in neighborhoods with the most soft-story apartments, also known as dingbats.

The Palms neighborhood on the Westside has more of these vulnerable buildings than any other neighborhood in the city, with almost every single building a dingbat on some blocks. In Palms, there are more than 700 suspected soft-story buildings holding more than 9,000 residential units. About 30% of the buildings have been retrofitted so far.

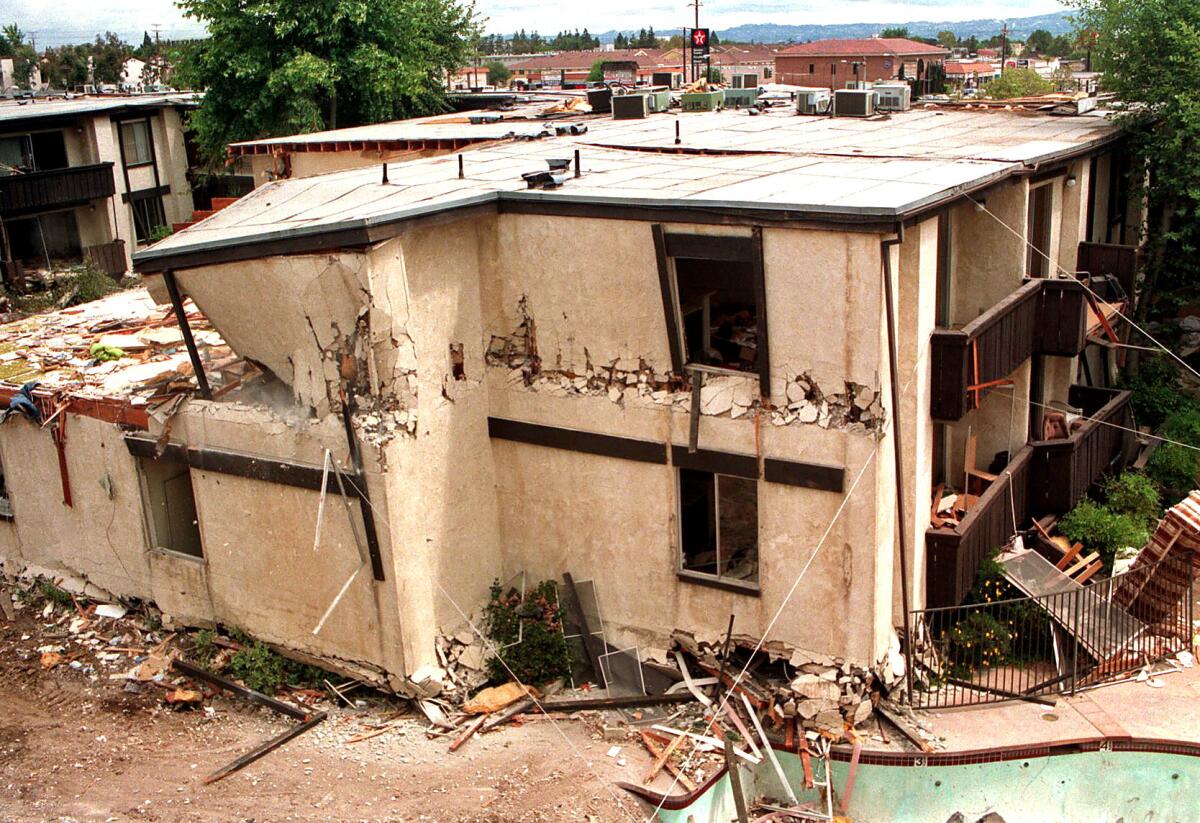

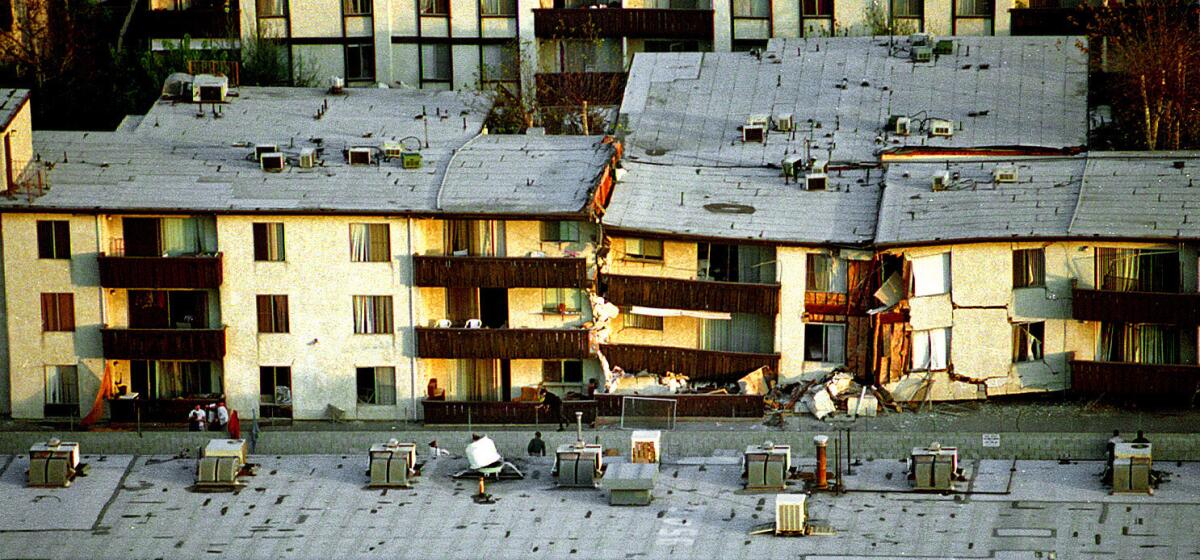

The completion of more than 3,000 apartment building retrofits in Los Angeles represents a big advance in strengthening dangerous soft-story buildings across California. It’s a type that caused the death of 16 people when the Northridge Meadows apartment complex collapsed in the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994, and at least three people, including a baby, in San Francisco during the magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989.

In Los Angeles, the retrofits represent significant progress for a city that only in 2015 passed a sweeping earthquake retrofit law authored by Mayor Eric Garcetti for these vulnerable wood buildings with a flimsy ground floor. Building owners in L.A. have seven years once they’re notified to retrofit.

“When we think about preparing for a major earthquake, our first thought has to be about saving lives — and I know that aggressive action on these retrofits will make that difference when the Big One hits,” Garcetti said in a statement. “Our progress is ahead of schedule, but we have to keep pushing to make certain that we get the job done as quickly as possible.”

While many California cities have long resisted forcing owners to retrofit these apartment buildings, more local officials in recent years have expressed interest in focusing attention on the issue. In October, Culver City released a report that said there were more than 600 potentially vulnerable wood soft-story buildings. Ontario has completed an inventory of seismically vulnerable buildings and staff is now studying the list, said city spokesman Dan Bell.

In May, the Pasadena City Council backed a mandatory retrofit law estimated to affect nearly 500 buildings, joining the ranks of Santa Monica, West Hollywood and Beverly Hills, which have all passed new laws in recent years to require soft-story apartment retrofits.

“For me, this is a public safety — life safety — issue, not for just the residents … but even those possibly who would be walking by in a major incident,” Pasadena Vice Mayor John J. Kennedy said at a council meeting in February. “We’re obligated to do something if we’re really serious about a safe city.”

Retrofits also lower owners’ liability by reducing the chance that people can be hurt when the earthquake hits, Kennedy said. A California appeals court decision in 2010 found that juries could hold owners financially responsible for people killed by their collapsing buildings if they did not take action to make them safer.

“It’s the moral, legal, right thing to do,” Kennedy said.

In Northern California, Oakland enacted a mandatory soft-story retrofit law earlier this year, joining San Francisco and Berkeley, which adopted similar laws in 2013 and 2014, respectively. In San Francisco, 67% of about 5,000 wood-frame apartments at least three stories tall and with at least five residential units have been retrofitted. About 79% of 292 soft-story buildings in Berkeley have been retrofitted, as have all 27 soft-story buildings known to exist in Fremont.

The East Bay city of Hayward, whose downtown is bedeviled by the Hayward fault, stopped short of a mandatory retrofit law. But the City Council recently passed a law requiring owners of nearly 300 suspect buildings with at least five units to have their apartments screened for seismic vulnerability and report the findings to the city.

Such programs can cause owners to voluntarily retrofit. Alameda in 2009 passed a similar law, and as of last year, out of 184 soft-story buildings, about 60% have been retrofitted.

Other cities have resisted taking action, citing the cost to property owners and concerns that the work could worsen California’s already serious housing affordability crisis. Some of Los Angeles County’s most populous cities that have many older buildings, like Long Beach and Glendale, haven’t passed laws recently requiring retrofit of soft-story apartments.

Neither has the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, which governs 1 million people in unincorporated communities that don’t have their own city councils, and is responsible for areas like East Los Angeles, Florence-Firestone and Hacienda Heights.

Why apartments can collapse in an earthquake. Flimsy ground story walls for carports, garages or stores can crumble in an earthquake, and are called “soft-story” buildings, explains U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Ken Hudnut.

There are also many other cities in Northern California that haven’t passed mandatory retrofit laws, including many in Silicon Valley, like San Jose, California’s third most populous city. More than 1,000 soft-story buildings might be in San Jose.

Soft-story buildings were generally built before 1980 and are vulnerable because the skinny poles holding up the apartment’s carports can snap in an earthquake, crushing people on the first floor. Just 14 months ago, only 5% of Los Angeles’ vulnerable soft-story buildings had been retrofitted.

In 2018, Long Beach, Los Angeles County’s second largest city, had discussed spending $1 million to identify as many as 5,000 potentially vulnerable buildings, but the City Council ended up not taking a vote on that idea.

In the coming months, the city plans to hire a consultant to study how other cities have tackled vulnerable buildings, said David Khorram, Long Beach’s superintendent of building and safety.

Retrofitting most soft-story apartment buildings costs $40,000 to $160,000, with most averaging around $80,000, according to a recent estimate presented to Culver City officials.

In cities with rent control, who should pay for the fixes has been the subject of some debate. The Los Angeles City Council determined that owners can pass half the retrofit costs to tenants through rent increases over a 10-year period, with a maximum increase of $38 per month.

San Francisco allows all retrofit costs to be passed onto renters, even those protected by rent control, over a 20-year period; the retrofit surcharge can be no more than 10% of the base rent. Low-income tenants can seek and receive hardship exemptions to rent surcharges related to the earthquake retrofit.

The Northridge earthquake that hit 25 years ago offered alarming evidence of how vulnerable many types of buildings are to collapse from major shaking.

Experts say retrofitting these buildings will not only save lives, but also preserve older, more affordable housing after a major earthquake, and keep rent checks coming through to landlords. The destruction of many older apartment buildings in a major quake would suddenly worsen the state’s housing crisis.

Just before the 25th anniversary of the Northridge earthquake earlier this year, experts noted that many California apartment owners have seen a big increase in property value, and a prudent use of that equity would be to invest it in a seismic retrofit. “It’s better to invest now,” said Heidi Tremayne, executive director of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute.

“The destruction of tens of thousands of units of housing after a big earthquake will bring on a housing crisis unlike anything we’ve ever seen,” Garcetti said earlier this year. “This is the rainy day. Spend it now before something bad happens.”

Los Angeles has also identified about 1,300 soft-story condo buildings that will need to be strengthened under the city’s earthquake safety law. So far, about 9% have been retrofitted.

In addition to soft-story apartments, Los Angeles, West Hollywood and Santa Monica have also required owners of suspected brittle concrete frame buildings to also conduct retrofits if they’re found to be hazardous in an earthquake.

A Times analysis in 2013 found that more than 1,000 older concrete buildings in Los Angeles and hundreds more throughout the county may be at risk of collapsing in a major earthquake.

Those retrofits are far more expensive, due to the large size of concrete buildings; the fixes could cost $1 million or more. Occupants probably would have to move out during the renovation, at an additional cost.

But the buildings can also be especially deadly when they collapse, owing to their enormous size. Just two of these buildings catastrophically collapsed in an earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2011, killing 133 people, accounting for more than two-thirds of the death toll of the entire disaster.

In Los Angeles, the collapse of concrete buildings during the Sylmar earthquake of 1971 killed 49 people at the Veterans Administration Hospital in San Fernando. Similar damage at Olive View Medical Center in Sylmar killed three people.

Steel-frame buildings designed before the Northridge earthquake are also a concern. Santa Monica and West Hollywood have passed laws requiring retrofits of those buildings; about 25 were significantly damaged in the Northridge earthquake, including one in Santa Clarita owned by the Automobile Club of Southern California that almost collapsed.

Los Angeles has not passed a mandatory retrofit law for steel frame buildings.

It’s plausible that five unretrofitted steel buildings could collapse in a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault in Southern California, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.