HEALDSBURG, Calif. — The things that set California apart, for better or worse, were all there last Sunday afternoon: terrifying flames, wine country glamour and a rescue straight out of Hollywood. Captured via smartphone. Of course.

As John Viszlay and Dominic Foppoli watched, horrified, the Kincade fire crested the foothills of the Mayacamas Mountains and headed straight for their adjoining vineyards. Winds gusted. Smoke swirled. At any moment, they realized, everything they’d worked for would be lost.

“We came within a couple hundred yards of the fire hitting and destroying our winery,” said Foppoli, who is also the mayor of nearby Windsor. It would have been a disaster, “if it wasn’t for a perfectly timed Hollywood scene, where the skies parted and a 747 supertanker … shows up out of the sky and blasts the fire.”

A bright pink plume of skillfully placed fire retardant saved Christopher Creek Winery, which was founded in 1972 and acquired by Foppoli’s family 40 years later. It spared Viszlay Vineyards, which has been operated by its eponymous owner and his son for the past decade. Beyond that, good news is in short supply.

Evacuation orders have lifted in Healdsburg, Windsor and most other swaths of Sonoma County. Vineyard owners and winemakers have been returning to their operations for the first time since the vast Kincade fire ignited, to assess the fire’s impact. Some tasting rooms are reopening.

For the most part, vines and wineries survived the flames, and, as of Saturday night, the blaze was 74% contained. But questions loom over how much of the 2019 vintage survived a week of intense heat, smoke and evacuation-caused neglect. How big an economic hit the region’s small, family-owned operations will take.

And whether the wine country’s carefully cultivated image can survive year after year of increasingly destructive fires, which are reshaping how the world views this region of rolling hills, orderly beauty, popping corks and clinking glasses.

“We don’t want this to be our new normal,” said Karissa Kruse, president of Sonoma County Winegrowers. “We love people visiting Sonoma County and our fellow wine regions and having a great experience. We don’t want people to worry about coming here. We have some work to do.”

When Sonoma County isn’t reeling from disaster, it is among California’s most scenic and verdant regions. Grapevines march in graceful rows — bright green in spring, lush with fruit in summer, deep red and gold in the autumn chill. The Russian River snakes through the Dry Creek Valley and Russian River Valley grape-growing regions to the ocean. There are stately redwoods, 50 miles of rugged Pacific coastline, more than 425 wineries. It is Napa’s relaxed and welcoming sister.

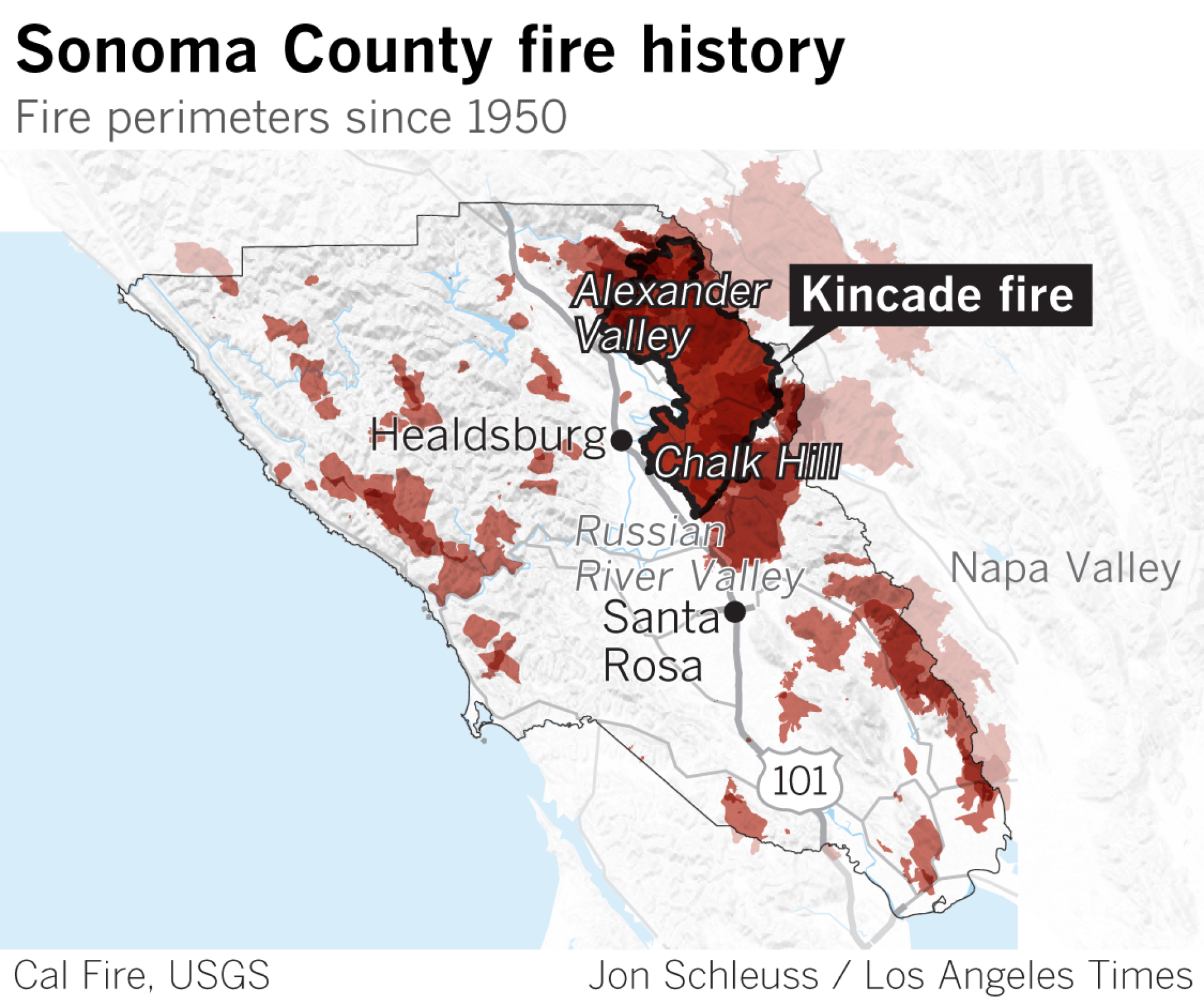

Christopher Creek Winery is located at the northern tip of the Russian River Valley grape-growing region. Three other famous viticultural areas spread out in the distance: Dry Creek Valley, Alexander Valley, Chalk Hill. On Wednesday afternoon, a week into the Kincade fire, a stripe of cement-colored smoke separated foothills from blue sky.

“Even today, outside of the haze, if we clean the pool out, and we didn’t know about the fire, we could be sitting around and enjoying a bottle of wine and being as happy as we were a week ago,” Foppoli said. “We need people to understand that.”

President Trump’s comments contrast with the types of California fires that blazed: Westside’s Getty fire, suburban Easy fire, mountain-based Maria fire.

That, however, is a big if. On that crisp October day during wine country high season, Healdsburg was still under evacuation orders. California Highway Patrol officers and military police guarded the barricaded off-ramps along the 101 Freeway. The twisty, two-lane roads between wineries were empty.

Foppoli and Mike Brunson, Christopher Creek’s winemaker, had just taken their first look at the 2019 harvest. On the plus side, about 95% of their grapes had been harvested before the fire hit. On the very big minus side, the fruit had recently been crushed and was early in the crucial fermentation process.

At high-end, boutique wineries such as Foppoli‘s and Viszlay’s, winemakers are in attendance seven days a week during fermentation, breaking up the cap of grape solids, skins and stems that forms over the juice and mixing it back in three or four times each day. They monitor the liquid’s chemistry, as its sugars are converted into alcohol.

But this wine-to-be had not been touched for four days. The power was turned off in the combustible region, so the tanks and barrels inside the winery had heated up to dangerous temperatures as the fire neared. Because the winery is so small, 13 big plastic tubs and half a dozen wooden barrels of fermenting liquid are kept outside. The tubs produce 600 bottles of wine each; the barrels, 200 each.

Brunson opened up a white fermenting tub and stared at the crushed zinfandel grapes inside.

The farmworkers who called Francisco Pardo the morning after the Kincade fire began were more anxious than usual.

The two men looked crestfallen.

“It’s supposed to smell like fresh fruit and a little bit of alcohol and a little bit of carbon dioxide,” Brunson said. “That’s the byproduct. Now you can smell the starting of a vinegar, nail polish, ethyl acetate-y thing.”

Foppoli added: “We’re looking at a multimillion-dollar loss here.”

He walked away and came back with a magnum of 1992 Petite Sirah , a so-called library wine. The thin, pliable metal capsule that seals the cork in the bottle’s neck had been pushed out of shape.

“When you start getting too much heat, it expands and pushes the cork out,” Foppoli said. “And the wine’s ruined. ... This [bottle] would be $300 to $400 if there was a price on it. There’s an entire room, you can see the barrels bleeding out because of the heat.”

He let out a deep sigh of grief and frustration.

Soda Rock Winery in neighboring Alexander Valley fared even worse. As of Saturday morning, the Kincade fire had torched nearly 80,000 acres and destroyed 372 structures. Of those, 175 were houses. One was the historic winery, which started out in around 1870 as the Alexander Valley general store. Soda Rock is owned by Wilson Artisan Wineries, which has 10 such boutique properties in Northern California.

Today, all that’s left is the barn, an outsize metal sculpture of a charging boar named Lord Snort and a single, long stone wall. In the days after fire swept through, Soda Rock became the image of all that had been lost here.

“The past few days has been devastating for Sonoma County,” the company wrote on the Soda Rock website. “In particular, we have experienced tremendous heartbreak with the loss of the Soda Rock Winery, the winery that you may have seen tragically burning on national TV.”

“What we hold onto in these trying times is the safety of our staff, wine club members and wider community,” the company said. “Quite a bit of Soda Rock’s wine storage is offsite, so there was little damage to inventory.”

The fire’s impact — which is considerable — was mostly felt by wine industry workers who were unemployed while their job sites and homes were under evacuation orders. And by small, family wineries that sell most of their wares from tasting rooms, which have been closed during this, the end of the high season. And possibly by the 2019 vintage itself.

“The impacts are big,” Windsor Councilwoman Esther Lemus said Wednesday. “Wineries are shut down. Employees cannot get to the work place, so people are losing wages. I’m already starting to receive phone calls of people asking, ‘What types of services will be available to me? I’m not getting paid. I’m not working.’”

The ripple effects of the fire could last into the future. Most wineries store wine in warehouses off site, so they’ll still have inventory from past vintages to sell. That’s the case at Christopher Creek. But in two or three years, when it comes time to market the 2019 vintage, operations like Foppoli’s and Fritz Underground Winery could be in trouble.

“If we lose the [2019] vintage, there’s nothing to back it up,” said Clayton B. Fritz, president of Fritz Underground and a board member of the Sonoma County Vintners Co-op. “We can’t make more. Two years from now, there’s nothing to sell. That’s another problem.”

Fritz said it’s too early to assess the condition of four lots of high-end Cabernet Sauvignon and zinfandel at his operation. They were kept in open-topped fermentation vessels, and he fears they may have been damaged. They account for 2,000 cases of wine, or 24,000 bottles, and make up about 20% of his winery’s output.

Christopher Creek and Viszlay wineries were still without electricity Friday, and their tasting rooms remained closed. But Fritz got power back on Halloween night, and reopened his tasting room Friday.

Nobody showed.

“I feel really bad for Soda Rock,” Fritz said. “It’s a winery gone, and it’s on the news, and people are like, ‘Oh, my God, the wine country’s on fire.’ You’ve got to remind people that Sonoma County’s one of the great agricultural counties of the world, and it goes from the coast to that other valley called Napa that we talk about sometimes.”

Fritz’s message post-Kincade fire is simple: Sonoma County “is not destroyed.”

So is Foppoli’s: “The best way people can help is to come drink wine.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.