Bay Area earthquakes are latest warning of destructive seismic danger in East Bay

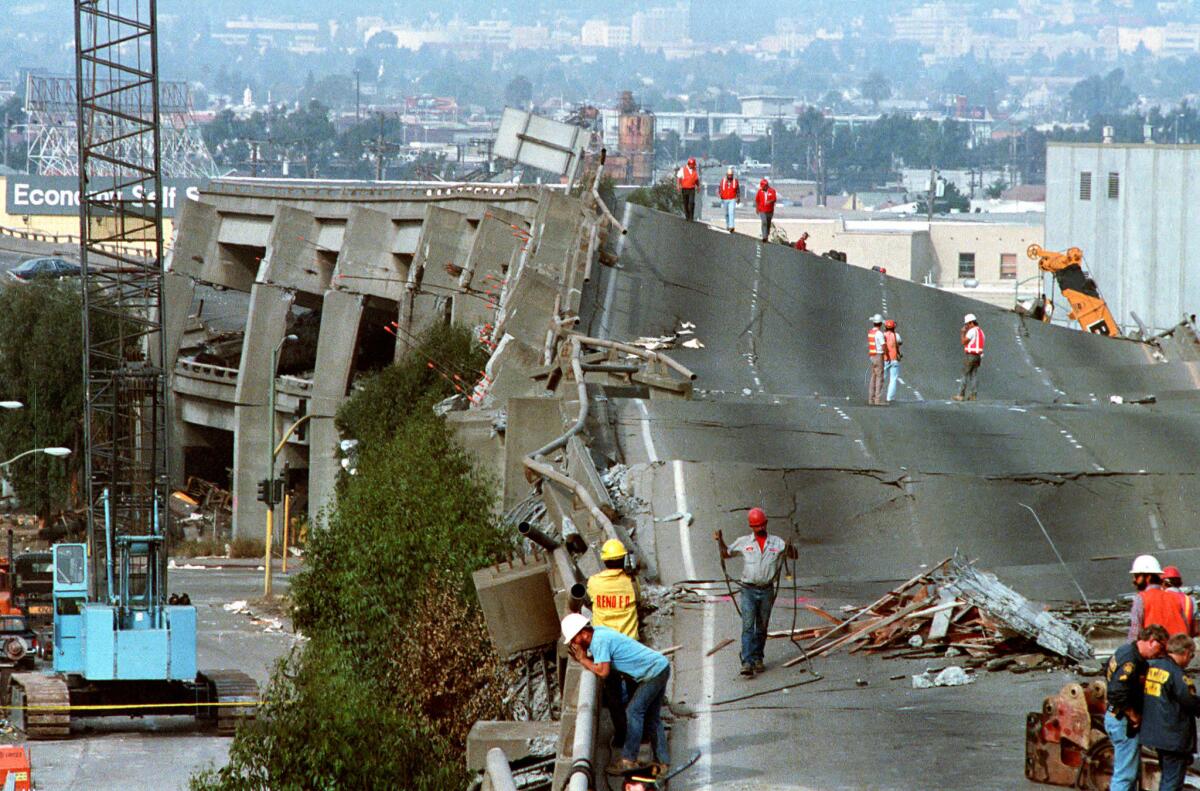

Two moderate earthquakes in Northern California 100 miles from each other in less than 15 hours unnerved the Bay Area just days before the 30th anniversary of the Loma Prieta earthquake.

The quakes began Monday at 10:33 p.m., when a magnitude 4.5 temblor rattled out of the suburbs of Contra Costa County, in the East Bay about 20 miles northeast of San Francisco. Then, on Tuesday at 12:42 p.m., a magnitude 4.7 quake struck in the remote mountains of San Benito County. No major structural damage was reported.

Monday’s quake was the latest reminder that seismic forces put the East Bay at high risk of a major earthquake, including from the dangerous Hayward fault, which runs along heavily populated areas. Californians will undergo the annual earthquake drill called ShakeOut on Thursday, which falls on the anniversary of the magnitude 6.9 earthquake in Northern California that killed 63 people.

The epicenter of Monday’s quake was an unincorporated area surrounded by Walnut Creek, Pleasant Hill and Concord. The earthquake had a preliminary depth of about nine miles underneath the surface, fairly deep for this part of the world, Keith Knudsen, USGS geologist and deputy director of the agency’s Earthquake Science Center, said in an interview.

The depth of the quake caused it to be felt over a broad area, but the shaking felt at the surface was less intense than if the quake had been more shallow, scientists said.

Q: What do we know about the area of the epicenter of Monday’s quake?

The earthquake was not directly on top of any of the main Bay Area earthquake faults. The epicenter was about three miles west of the Concord fault, and farther than that off the northern end of the northern Calaveras fault, Knudsen said.

The epicenter is just northwest of Mt. Diablo, one of the Bay Area’s tallest peaks. The Mt. Diablo area is also a seismically active zone, “a region of uplift, folding and thrusting,” said David Schwartz, USGS scientist emeritus.

There was a series of earthquakes in the magnitude 5 range on the southeast side of Mt. Diablo in 1980 in the Greenville fault area. The Greenville fault area, one of the Bay Area’s seven most significant faults, ruptured with quakes of magnitudes 5.8 and 5.1 on Jan. 24, 1980, that were, respectively, 12 and nine miles north of Livermore.

On Jan. 26, 1980, a magnitude 5.4 quake hit with an epicenter only six miles from downtown Livermore. Damage in 1980 was reported at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and a mobile home park.

On July 16, a magnitude 4.3 earthquake hit near the northern side of the Greenville fault, about 11 miles northeast of downtown Livermore. It hit on the western edge of the Los Vaqueros Reservoir, which holds water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and is an important water source in the late summer and early fall, when high levels of salt creep into the delta; no damage was reported.

Q: What do we know about seismic risk on the Concord-Green Valley fault?

The Concord-Green Valley and Calaveras faults are among the Bay Area’s most significant.

A hypothetical magnitude 6.8 earthquake on the Concord-Green Valley fault is capable of causing strong shaking in Contra Costa, Solano and Napa counties, and could cause damage to the Kinder Morgan Concord pumping station, responsible for pumping fuel across the northern half of California, the Assn. of Bay Area Governments said in a report published in 2014. All five of the Bay Area’s refineries export their refined fuel through that Concord pumping station.

There are separate refined fuel pipelines that reach San Jose and Brisbane from the Chevron refinery in Richmond, but they represent a small share of the region’s fuel supply, the report said.

Such a plausible quake would be strong enough to cause liquefaction in all Bay Area counties. Strong shaking would also be felt in the Carquinez Strait, the narrow waterway connecting San Francisco and San Pablo bays to California’s two longest rivers, the Sacramento and San Joaquin; the shaking could cause the edges of dredged water channels to fall into the waterways, according to the association.

The last large quake on the Concord-Green Valley fault occurred in 1610. A more moderate magnitude 5.4 earthquake occurred on the fault in 1955.

Q: What about the Calaveras fault?

The Calaveras fault can produce a quake in the magnitude 7 range, and it’s possible that it could rupture jointly with the Hayward fault, one of the nation’s most dangerous because the Hayward fault runs directly underneath densely populated cities in the East Bay, such as Oakland, Berkeley, Hayward and Fremont.

The largest historical quake on the Calaveras fault was a magnitude 6.6 temblor in 1911, according to Ross Stein, chief executive of Temblor.net and a former USGS research geophysicist.

One swarm in 2015 that occurred close to the Calaveras fault generated 4,000 quakes over five months, according to the Berkeley Seismology Lab. The cluster of quakes occurred in the San Ramon Valley, which has had many swarms over the last several decades that haven’t resulted in a large earthquake.

Q: What about the Hayward fault?

A landmark report published in 2018 by the U.S. Geological Survey estimates that at least 800 people could be killed and 18,000 more injured in a hypothetical magnitude 7 earthquake on the Hayward fault centered below Oakland.

Hundreds more could die from fire following an earthquake along the 52-mile fault. More than 400 fires could ignite, burning the equivalent of 52,000 single-family homes, and a lack of water for firefighters caused by old pipes shattering underground could make matters worse.

The Hayward fault is so dangerous because it runs through some of the most heavily populated parts of the Bay Area, spanning the length of the East Bay from the San Pablo Bay through Berkeley, Oakland, Hayward, Fremont and into Milpitas.

Out of the region’s population of 7 million, 2 million people live on top of the fault, Schwartz has said, and that proximity brings potential peril.

The Hayward fault’s most memorable earthquake in recorded history was in 1868, and is estimated to have been a magnitude 6.8 earthquake — rupturing 20 miles of the fault’s length between San Leandro to what is now the Warm Springs neighborhood of Fremont, according to the USGS.

It killed about 30 people and caused immense property damage, including the collapse of the Alameda County Courthouse’s second floor and heavy damage at the historic Mission San Jose adobe church in southern Fremont.

What are the Bay Area’s other major earthquake faults?

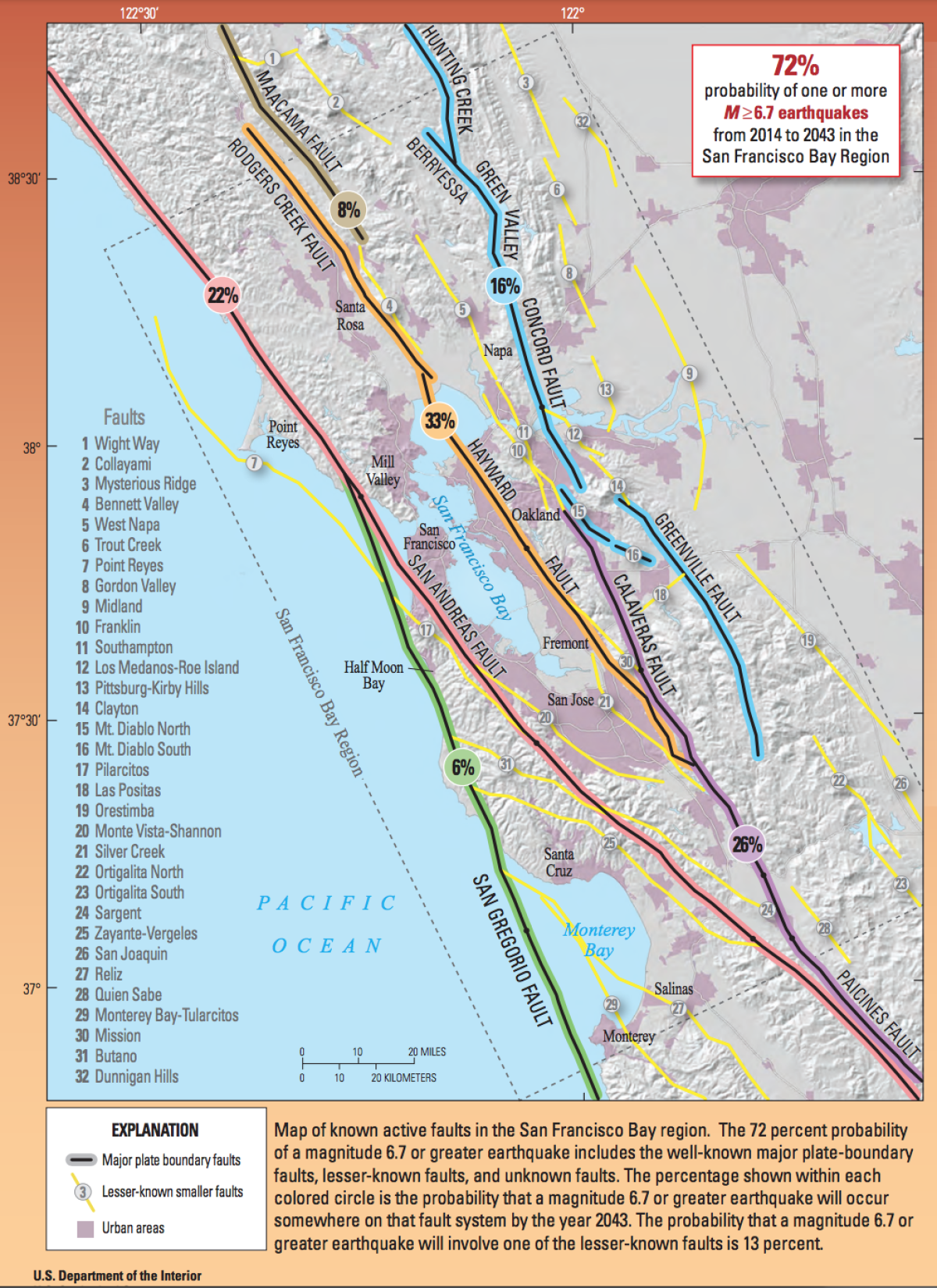

The seven significant earthquake fault zones in the Bay Area are all roughly parallel to each other. Besides the Hayward, Calaveras, Concord-Green Valley and Greenville faults, here are the three others:

• San Andreas fault: The world’s most famous fault, the San Andreas triggered the great 1906 earthquake, estimated to be a magnitude 7.8 event that ruptured an astonishing 296 miles of fault, between San Juan Bautista and Cape Mendocino. The quake and resulting fires leveled much of San Francisco and is believed to have killed at least 3,000 people and destroyed 28,000 buildings.

The quake produced 22 times more energy than the magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, which killed 63 people; the 30th anniversary of that event is Thursday. (The Loma Prieta earthquake, centered in the Santa Cruz Mountains, occurred on a neighboring sub-parallel strand of the San Andreas and not on the main fault itself, according to USGS research geologist Kate Scharer.)

• Rodgers Creek fault: The Rodgers Creek fault runs through Santa Rosa. The USGS said in 2016 that a large earthquake on the Rodgers Creek fault has the potential to intensely shake the sedimentary basin beneath Santa Rosa.

On Oct. 1, 1969, there were two damaging quakes near Santa Rosa of magnitudes 5.6 and 5.7, which at that time were the largest temblors in the Bay Area since 1906.

The Rodgers Creek fault is capable of a quake in the magnitude 7 range.

• San Gregorio fault: The San Gregorio fault runs west of the San Andreas, roughly off the coast of the Bay Area and along seashore areas of Marin and San Mateo counties, continuing south toward Monterey Bay. The most recent large event on this fault — between magnitudes 7 and 7.25 — probably occurred between 620 and 1400, according to a study in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America published in 1997.

What do we know about the San Benito County earthquake?

Strong shaking hit the remote Diablo range in between Monterey and San Benito counties, but only weak or light shaking was felt in the Salinas Valley, Monterey, Gilroy, Los Banos and the Bay Area.

Still, the quake caused swaying for several seconds on the fifth floor of a building in Foster City in San Mateo County; in San Ramon in the East Bay, a chair could be felt moving back and forth on the fourth floor.

The East Bay and San Benito County quakes were not related and are not part of the same fault system.

Along what fault did Tuesday’s quake hit?

It occurred along the creeping section of the San Andreas fault, a length of roughly 90 miles that is notable for not having had dramatically large earthquakes in the modern historical record. For this section of the fault, Knudsen called Tuesday’s quake “a garden variety San Andreas event.”

“This is the 10th earthquake larger than magnitude 4 in the last 20 years in this area,” within a radius of about six miles from Tuesday’s epicenter, Knudsen said.

The stretches of San Andreas north and south of the creeping section have acted very differently in the modern historical period, rupturing in the state’s largest catastrophic quakes on record.

What is the north and south of the creeping section of the San Andreas fault?

The northern San Andreas fault ruptured in the great 1906 earthquake. It ruptured 300 miles of fault between San Juan Bautista in San Benito County and Cape Mendocino.

A long swath of the southern San Andreas last ruptured in 1857. A 225-mile stretch ruptured from Parkfield in Monterey County to Wrightwood in San Bernardino County.

Both quakes are estimated to have been magnitude 7.8.

The creeping section hasn’t seen a big earthquake in the modern record. The question of whether big earthquakes can continue to rupture through the creeping section of the San Andreas is still being studied.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.