As anti-Semitic crimes rise and Holocaust awareness fades, a survivor is always ready to speak

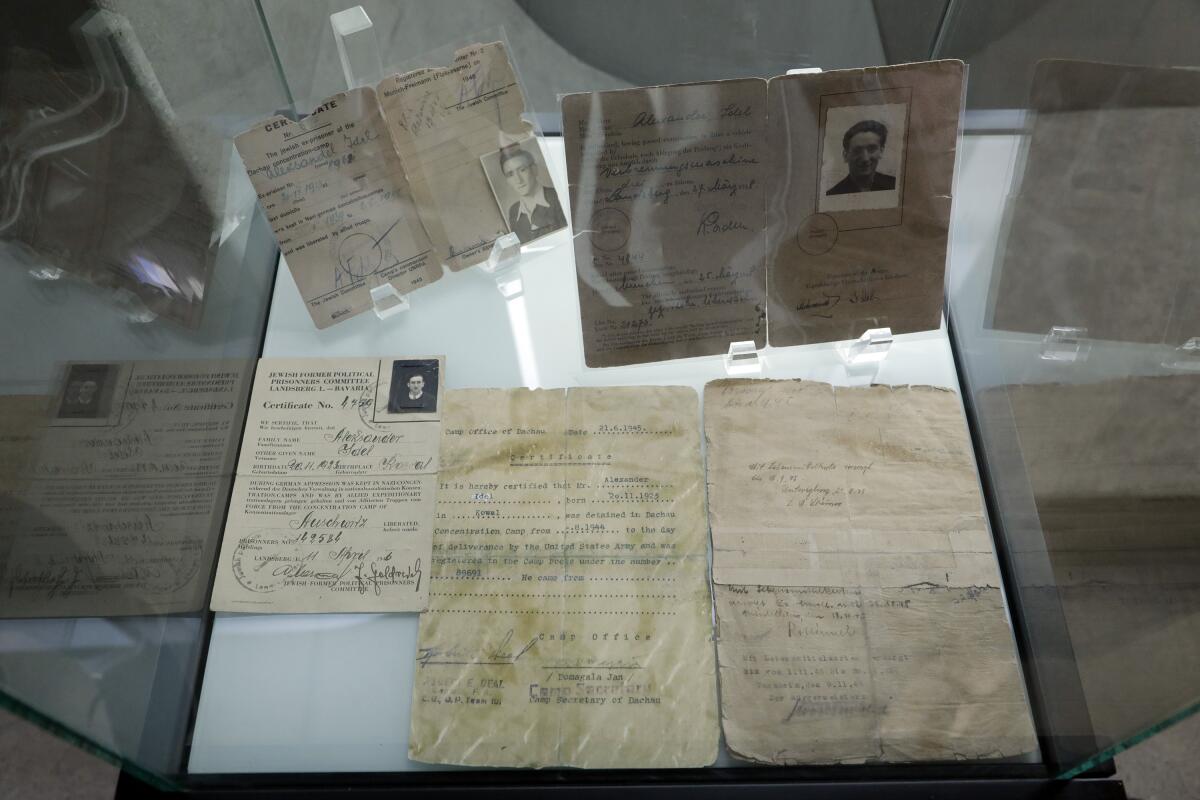

Joseph Alexander lifted his left forearm to show the number.

Nazi guards had tattooed it on him just after he and scores of other Jewish prisoners arrived by cattle car to the Auschwitz concentration camp along with the bodies of those who didn’t survive the train ride.

For the record:

9:42 a.m. Sept. 10, 2019This article states that Joseph Alexander worked as a tailor for 27 years. Alexander actually spent 37 years running a military uniform shop on Melrose Avenue.

“From that moment on, we have no name,” Alexander said.

142584.

“That was your name.”

Alexander is 96. A slight man with a Polish accent, wearing a Hawaiian shirt, he is speaking on a sunny Sunday to a rapt crowd of about 30 at the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust. He’s telling his story about six years and a dozen concentration camps. About how he survived and his family didn’t.

He’s been giving speeches like these, sometimes three a day, for 15 or so years and has talked to thousands of students. At this museum, he considers himself essentially on call.

For Alexander, there is a growing urgency to telling his story to as many people — especially young people — as possible, as the number of aging Holocaust survivors dwindles and the horrors of the Nazis fade into the past. Forgetting comes with a price.

In March, a group of teenagers from Newport Beach and Costa Mesa were pictured giving the Sieg Heil salute beside red plastic cups arranged into a swastika at a house party.

That same month, school officials in Garden Grove were alerted to a group of Pacifica High School students raising their arms in Nazi salutes while singing an obscure Nazi marching song at an off-campus athletic event. A Snapchat video of the incident exploded online this month after it was sent to the Daily Beast.

Also in March, Los Angeles police found two swastikas scrawled in blood in Pan Pacific Park, near the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust.

The incidents come as anti-Semitic hate crimes are rising — by 54% from 2014 to 2017, according to the FBI.

Knowledge of the Nazi atrocities among young people is decreasing. A study commissioned last year by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany showed that 66% of U.S. millennials did not know what Auschwitz was. Four in 10 millennials thought 2 million or fewer Jewish people were killed during the Holocaust; the actual number is around 6 million.

“Time, fragmented online echo chambers and ignorance have enabled bigotry and Holocaust denial a renaissance,” said Brian Levin, director of Cal State San Bernardino’s Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

This month, President Trump repeatedly said American Jews who vote for Democrats are “disloyal,” drawing sharp condemnation from major Jewish groups, which said the comments were anti-Semitic. Trump also tweeted a quote from conspiracy theorist Wayne Allyn Root saying “the Jewish people in Israel” love Trump “like he’s the King of Israel.”

In recent months, the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, the Museum of Tolerance and local Jewish educators and rabbis have reached out to high schools in Orange County scandalized by Nazi-related social media posts, offering to teach students about the Holocaust.

“History can and will repeat itself, and that’s why, if we forget what took place and what people have the capacity to do to each other, we can slip into it again,” said Jordanna Gessler, director of education at the L.A. Museum of the Holocaust. “You don’t always have to agree with people and you don’t always have to love people, but you have to respect people.”

Gessler’s Polish grandfather lived through the Holocaust and lost his mother. He suffered from survivor’s guilt and rarely talked about what happened.

“There’s not too many of us left,” said Alexander, the 96-year-old survivor. “Especially now, if we don’t talk, if we are gone, there will be nobody to talk about it, and people won’t know because they won’t see the original people who survived, who can tell you the story.”

In 1939, Alexander, the second-youngest of six children, was 17, living with his family in Kowal, the small town in central Poland where he was born. His father was a tailor.

That September, Germany invaded Poland. Soldiers ordered most people living near the Alexanders into the town square to be taken away. Somehow — Alexander never understood why — his family was spared, but rumors flew that the soldiers would return in three days to take the remaining Jewish families. The Alexanders fled to the town of Blonie.

Within days, Alexander was sent to a forced labor camp in the Kampinos Forest, where he worked in cold weather, standing in water up to his knees without boots, building a canal. Sores covered his legs and arms. He contracted blood poisoning.

In the fall of 1940, the Alexanders were deported to the newly created Warsaw Ghetto, a 1.3-square-mile space where more than 400,000 people were imprisoned behind a wall topped with barbed wire. Food was scarce.

“People were dying every day,” Alexander said. “You went out in the morning, and there were dead people on the sidewalk. Everywhere.”

Alexander’s father bribed the guards to let Alexander, his older sister and his younger brother escape back to Kowal. He never saw his parents or other siblings again. The three children made it home. But after three days, all Jewish males ages 16 to 60 were ordered to the schoolhouse. Alexander was taken by train to another forced labor camp, then several others. He built a dam, dug trenches for sewer lines, laid railroad tracks. The only food, he said, was a small square of bread in the morning. After work, it was watery soup made from potato peels.

One day, another train arrived. Alexander was packed into a cattle car with scores of prisoners, and for three days they rode with no food, water or restrooms. Many died.

The train stopped in a town near Auschwitz, where surviving passengers met Josef Mengele, the infamous Nazi doctor known as the Angel of Death, who was accused of sending up to 400,000 people to gas chambers and performing gruesome medical experiments on prisoners.

Mengele separated the passengers into two lines, to the left and the right. Alexander was sent to the left and saw that he was standing near elderly and sick people. He slipped to the other side.

“At every camp, I always tried to go to work,” Alexander said. “I always tried to get in with the biggest and strongest men. If I hadn’t gone back to the other side, I wouldn’t be here talking to you.”

The next morning, those on the left were taken to the gas chambers. Those on the right walked four miles to Auschwitz.

In 1943, Jewish prisoners staged the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, an armed revolt against Nazi officials who had come to deport them to extermination camps. The Nazis set the ghetto ablaze. Alexander was among a group of Auschwitz prisoners sent to dismantle the rubble and clean the bricks so the Nazis could reuse them.

His tattered clothing was covered in lice. He contracted typhus and hid for days behind a pile of bricks, waiting for his fever to break. He didn’t want to go to the hospital, because nobody ever came back.

Eventually, Alexander was sent to the Dachau concentration camp and its sub-camps in Germany. In 1945, American troops approached. Alexander and a small group of prisoners were sent on a death march away from Dachau, toward a mountainous area where they were to be killed. But the German guards disappeared as Allied forces neared.

A friend who had volunteered to take sick prisoners into a nearby village stumbled across a dead horse in the snow, cut off pieces of it and brought it back to Alexander. They made a barbecue in the forest — the “best meal we’d had in a long time.”

The next day, the Americans liberated them.

Alexander found one cousin who survived. He never learned what happened to his parents and siblings.

During the war, he received one letter from the sister with whom he briefly escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto, saying that she had been moved to another ghetto and that the 12-year-old brother who fled with them had been taken to a death camp and was placed in a truck where he was gassed. He never heard from her again.

Alexander, sponsored by a Jewish organization, arrived in the U.S. in 1949. He worked as a tailor on Melrose Avenue near Paramount Studios for 27 years, making military uniforms for TV and movies, and had two children.

“What got me through is I never gave up,” Alexander told the audience. “I never lost hope. I always say: ‘I may have a bad day today. Tomorrow will be a better day.’”

Then he spoke pointedly.

“There are a lot of Holocaust deniers out there, and you see a lot of what’s going on in the schools now. Don’t believe what they tell you.”

In the audience, Jena Frankel listened with her daughter, Presley, who is preparing for her bat mitzvah next year.

Frankel, 48, of Beverly Hills grew up with survivor stories. Her mother was born in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and her grandfather and all his friends had tattoos on their arms. In Hebrew school and public school, Frankel learned a lot about the Holocaust, but her two daughters, 12 and 16, just don’t seem to hear about it as much, she said.

“There are so many Holocaust deniers and so few survivors,” she said. “It’s part of my history. It’s our job to remember and educate people about it.... Anti-Semitism is on the rise, and it’s scary.”

Like Alexander, Frankel’s Hungarian grandmother was taken to Auschwitz by train. Disembarking passengers were separated: left and right.

They were told to hand young children to elderly prisoners, who would be going to the gas chambers. Frankel’s great-grandmother, holding her 4-year-old daughter, couldn’t bear to put her down. They both were killed.

In the camp, Frankel’s grandmother got dysentery and, at one point, tried to kill herself on the electric fence because she didn’t think she would survive.

“My grandma had her 15th birthday at Auschwitz,” Frankel said. “I look at my daughter at 16, and I can’t imagine what my grandma survived.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.