Summer learning loss: How teachers mobilize when kids return to school

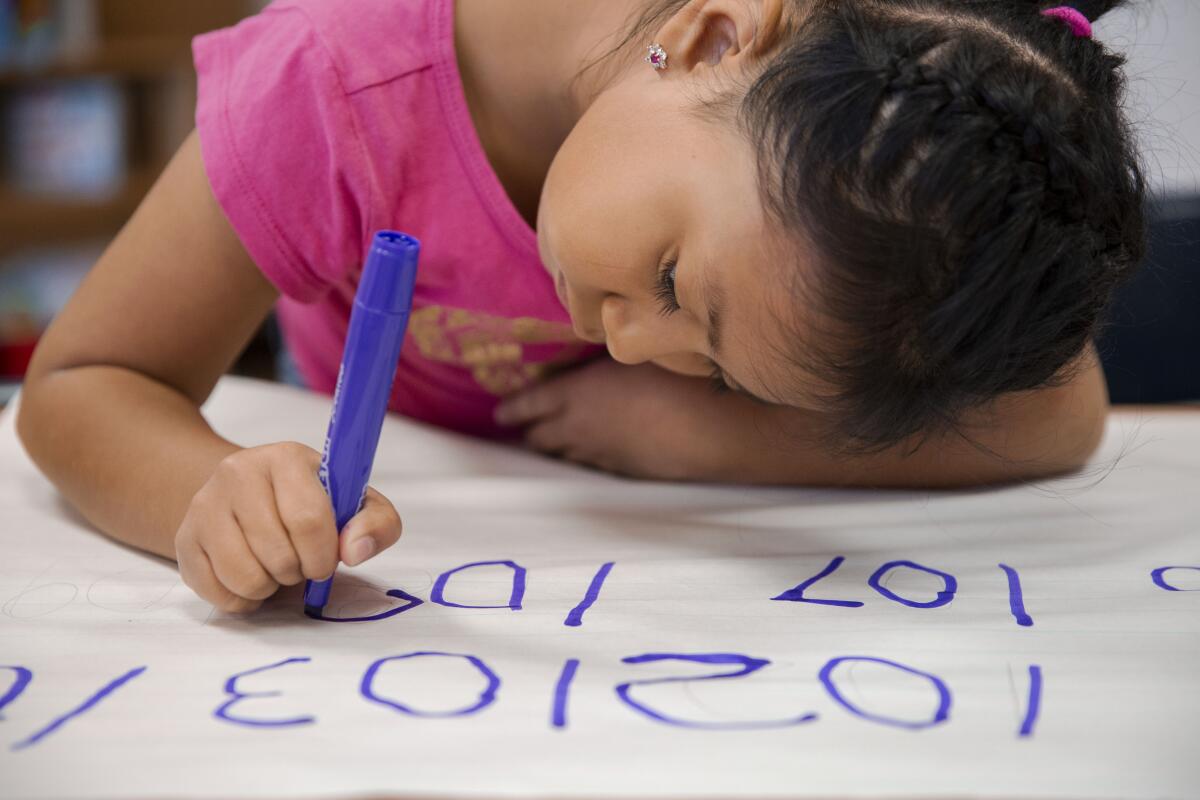

In a classroom just west of downtown Los Angeles, a dozen children gathered on a mat around teacher Genesis Aguirre, using dominoes to help them visualize the meaning of “horizontal” and “vertical” and how to count doubles.

“Does everyone feel confident?” Aguirre asked. “Confident means you feel ready to play your game.” Or, in the case of this two-week August intensive, ready to start first grade on Tuesday.

For the record:

12:43 p.m. Aug. 16, 2019An earlier version of this article referred to a group that helps educators create school assessments as the Northwest Education Assn. The group is known as NWEA.

Aguirre was on a mission to address the double back-to-school challenge confronting many teachers and students this time of year — summer learning losses compounded by gaps in learning from the previous school year.

The school-free summer months can bring on learning losses of one to two months in reading compared to the previous year, and up to three months of math learning, some studies show. If students never learned the material in the first place, though, typical back-to-school subject reviews may not be enough to launch students into new curriculum.

Week 1 of the new school year calls on teachers to dive into assessment mode to establish what their students know, what their strengths are, how to group students to maximize their learning time and whether they are at grade level.

“All of our teachers give baseline assessment — that’s an expectation,” said L.A. Unified’s interim chief academic officer, Alison Towery.

A thriving industry of summer academic and enrichment classes has long been available to families who can afford thousands of dollars in tuition or summer courses to help their kids get ahead. Some lower-income students can also access those courses in their communities or through partnerships that fund the programs and offer transportation.

Aguirre’s Esperanza Elementary School students did not have the math, literacy or interpersonal skills they were supposed to master in kindergarten, according to assessments and teacher recommendations. Her class is part of a districtwide pilot program for rising first graders designed to shore up learning gaps in their earliest school years. The hope is that keeping students on track at a young age will ensure fewer failed courses and on-time high school graduation.

“Our focus is on being proactive and preventing a gap from ever happening,” Towery said.

What happens to kids’ brains during the summer?

Education researchers have for decades studied summer learning loss — the math concepts and reading skills that slip away during three months of summer vacation — with varying conclusions.

A 1996 review of several studies on the topic found that most students lose two months of math skills every summer, and low-income children typically lose another two to three months of reading skills.

Data from the oft-cited Beginning School Study, which followed 800 Baltimore first-graders from 1982 to 2002, showed that summer learning loss during the elementary school years accounts for about two-thirds of the achievement gap between low-income children and their middle-income peers by ninth grade.

But some critics argue the earlier research was flawed and the associated claims inaccurate.

Paul von Hippel, an associate professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, tried to replicate some of the earlier studies on summer learning loss and reached different conclusions.

Modern test score data are overall inconclusive when it comes to summer learning loss. Some show it, others don’t, and the ties to achievement gaps are not as strong as they appeared in older studies.

For example, a study of 3.4 million students’ assessments in all 50 states found that the typical student did lose some learning over the summer. But gaps in learning based on race and income happen year-round; summer doesn’t exacerbate them, said study author Megan Kuhfeld, a research scientist with NWEA, a nonprofit that helps educators create school assessments.

The pattern she did find was somewhat surprising.

“Kids who gained the most in the prior school year seemed to show correspondingly larger drops during the summer,” Kuhfeld said.

Ideally, with the right intervention, students who are behind have a chance to close gaps in the summer with their peers who sped ahead or met grade level during the school year, experts said.

Combating the “summer slide” and addressing gaps

Robust summer programs can be helpful in maintaining and improving student performance over time — but only if students attend them consistently, according to a 2016 Rand Corp. study of more than 5,000 elementary school students.

Students who attended district-led, full-day voluntary summer programs that combined academics and enrichment for at least 20 days each summer, for at least two years in a row, were better off in math and reading and also in “social-emotional” skills such as self-awareness and regulation, the study found.

For students who start the school year behind — whether they never mastered a concept or simply forgot it — teachers have adopted a variety of strategies.

Kirsten Barajas, a middle-school math and English teacher at Soria School in Oxnard, starts out every school year with some review, including a multiplication test. She says students in her sixth-grade math class often struggle because they lack multiplication knowledge — an essential skill that they should have learned in the third grade. Because she must stay on schedule with her curriculum, she will assign review homework and encourage students who don’t know how to multiply to attend before-school tutoring.

“If you have those facts down automatic, it makes life in sixth grade so much easier,” Barajas said.

Other teachers take a different approach.

Sunanda Kushon, a math teacher and teacher advisor at Mann UCLA Community School, also assesses her students, and then jumps into the grade-level curriculum. As soon as she realizes a group of students don’t understand the basic concept beneath the problem, she backs up and reviews.

This approach saves time, Kushon said. Students don’t relearn what they already know, and the review comes at the moment they need it.

“I try to weave it into whatever the content is so we don’t fall behind,” Kushon said.

Akili Woods, an incoming junior who had Kushon as a math teacher in eighth and ninth grade, and will take a seat in her 11th-grade math and physics classes next week, said he spends about a month each summer attending the school’s Summer Institute, a program offered in partnership with UCLA that includes math instruction. Akili said he does forget material over the summer, and the program is especially helpful when he starts the school year again and is already familiar with new content.

“Most of the time I don’t understand it the first time, but if you show me again or if you slow it down, I’ll get it,” he said.

Akili learned about polynomials, for example, during a Summer Institute. When they appeared in class, the teacher applauded him for knowing what they were.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.