San Andreas fault is a 730-mile monster. Ridgecrest earthquake was a tiny taste of the possible destruction

Faults crisscross California, producing deadly earthquakes.

But whenever the ground shakes, the first thought always turns to the mightiest and most dangerous fault: the San Andreas.

This is the 730-mile monster capable of producing the Big One, the fault famous enough to be the main character in a hit disaster movie.

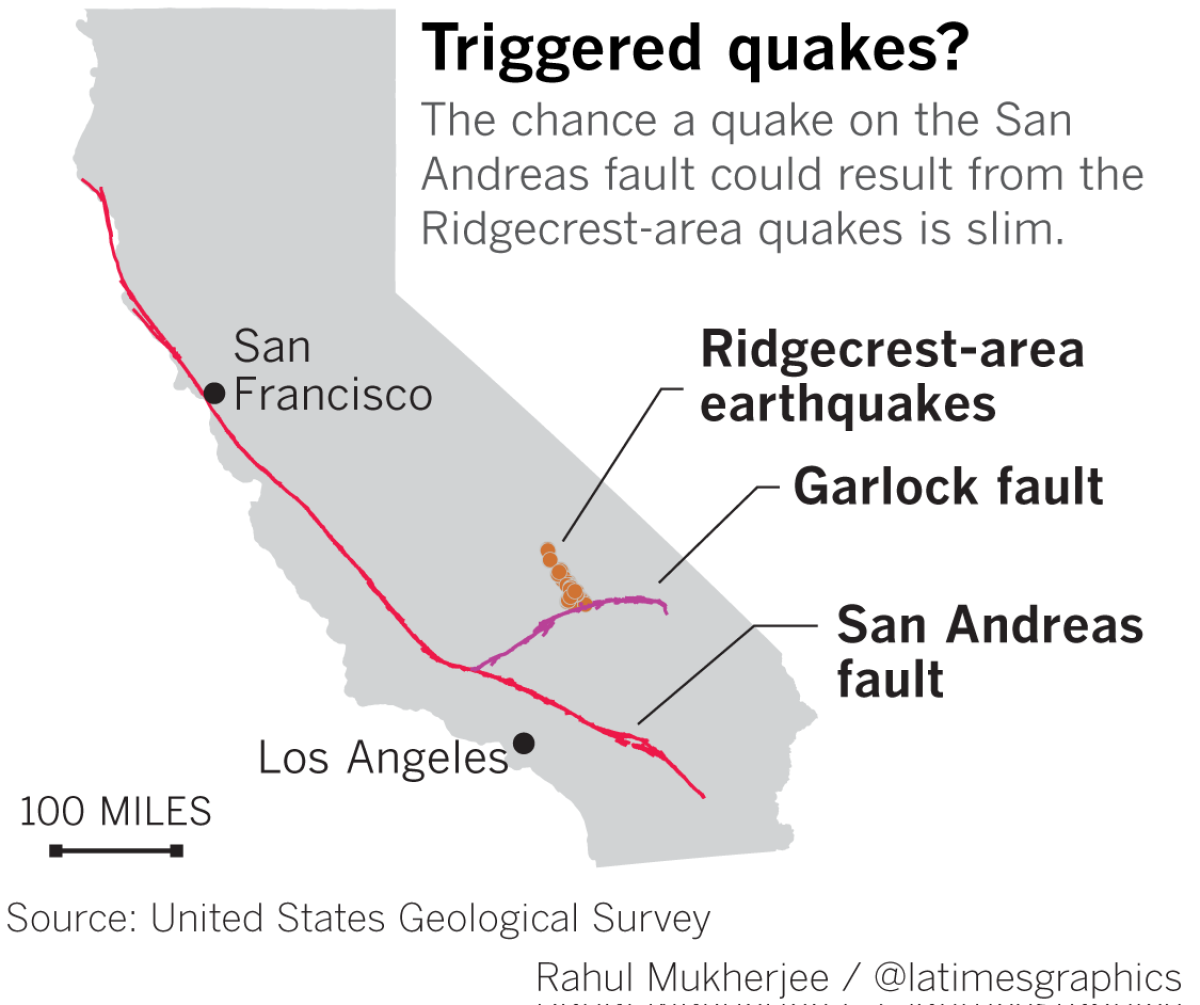

Scientists knew almost immediately that two large quakes that hit near Ridgecrest earlier this month did not come from the San Andreas.

But ever since, they’ve been studying whether the quakes could cause more seismic activity from other faults — including the San Andreas nearly 100 miles away.

A new calculation conducted in recent weeks at the U.S. Geological Survey showed that there’s an extremely remote chance the San Andreas could be triggered from the Ridgecrest quakes.

“It’s slim. But it’s the difference between slim and none,” said USGS seismologist Susan Hough. “I don’t think any earth scientists are going to lose sleep that this will cascade on to the San Andreas.”

But the fault remains a source of constant anxiety, especially when ground moves. Previous quakes on the San Andreas were triggered by earlier nearby temblors. The great magnitude 7.8 quake in 1857 that ruptured 225 miles of the fault between Monterey County to the Cajon Pass in San Bernardino County was preceded by a pair of smaller quakes one and two hours earlier.

Earthquakes in Southern California in 1992, 2001, 2009 and 2016 all sparked concerns from scientists they could trigger a major quake on the San Andreas. In some of those cases, officials even issued a public warning of heightened seismic risk. For example, after the twin quakes in Landers and Big Bear in 1992, state officials announced there was a 50% chance of another big temblor in the coming days.

None, however, caused the Big One on the southern San Andreas.

In the case of the recent temblors, the potential for the San Andreas to be triggered by the Ridgecrest quakes seems to be less of a concern, relatively speaking.

“We know that earthquakes can trigger other faults, even hundreds of miles away,” said USGS research geophysicist Morgan Page. “On one hand, the probability may go up. But it’s not a big increase compared to the risk we have year to year from the San Andreas, living in California.”

The recent calculation is highly theoretical and relies on a model known as the Third Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast, or UCERF3-ETAS, an epidemic-type aftershock sequence model that factors how an earthquake in one location can transfer seismic stress to a nearby fault.

Like anything being researched, it’s possible that this calculation about the San Andreas is wrong. A scenario like the one envisioned in the recent calculation — a Ridgecrest-to-San Andreas situation that spans some 100 miles — has not happened in California’s relatively short modern record.

The southern San Andreas is quite dangerous on its own and can rupture without any nudging from a distant Mojave Desert fault. And it’s accumulating seismic stress so fast that even if it did rupture soon, scientists would probably spend the rest of their careers arguing over whether the July quakes had anything to do with it, said USGS research geologist Kate Scharer.

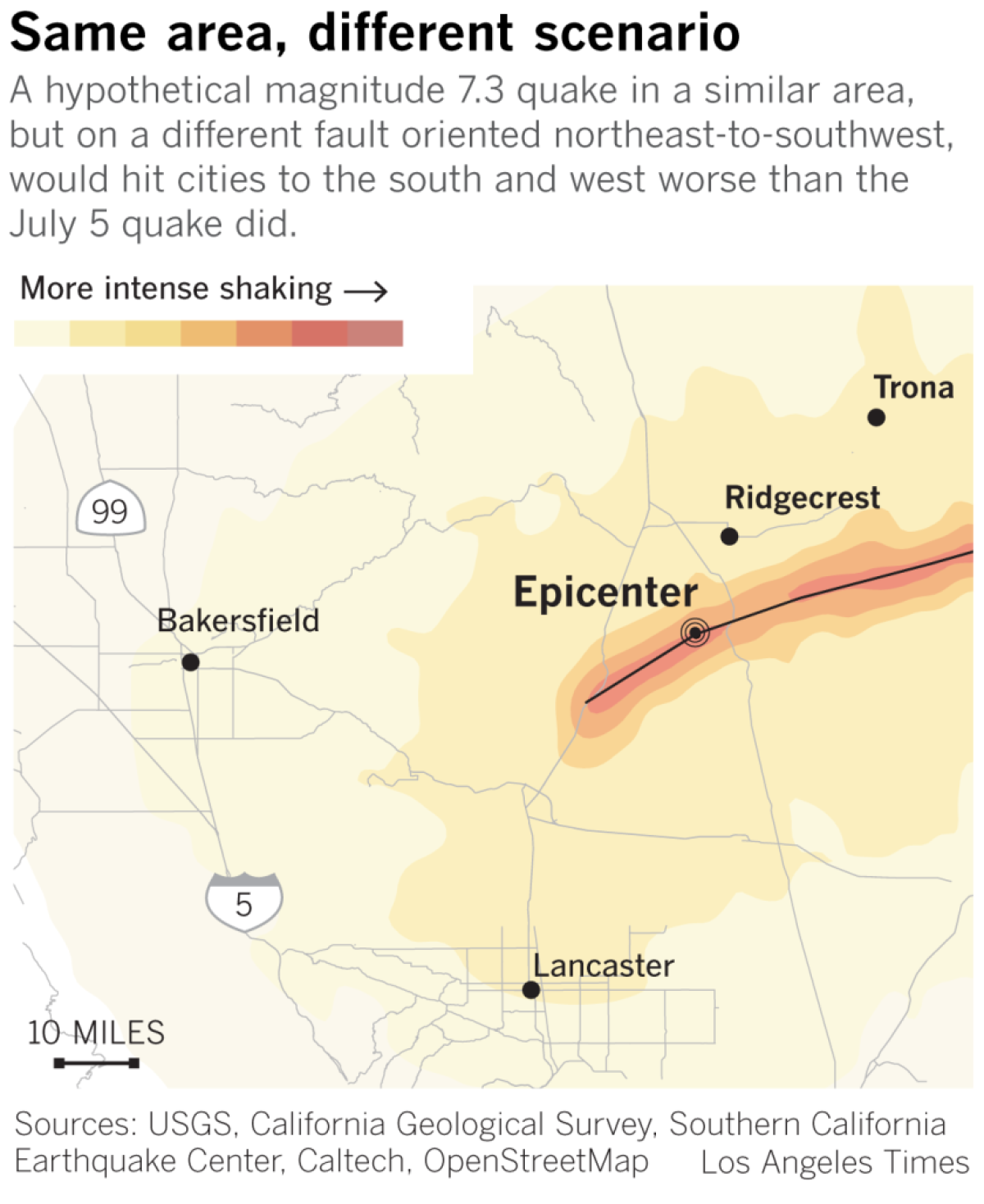

A big quake on the San Andreas would be devastating. The U.S. Geological Survey published a hypothetical scenario of a magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault that could kill 1,800 people, injure 5,000, displace some 500,000 to 1 million people from their homes and hobble the region economically for a generation. That quake would send strong shaking into Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Kern and Ventura counties almost simultaneously.

“There’s plenty of accumulated strain there,” Scharer said. “It’s the highest hazard fault, and it was before the [Ridgecrest] earthquake, and it will continue to be after the earthquake.

“It’s been quiet for so long.”

World-famous fault

The San Andreas fault has increasingly captured the imaginations of Californians over the years, likely assisted by the eponymous Hollywood action movie starring Dwayne Johnson in 2015, and its starring role in villain Lex Luthor’s evil scheme in the Superman movie of 1978.

Even when far-off earthquakes occur, the public’s appetite for any information about the San Andreas is insatiable. Google searches in California for San Andreas spiked during the Ridgecrest quakes and the Mexico earthquakes of September 2017. TV news chyrons earlier this month blared with text how the Ridgecrest quakes were not on the San Andreas.

The obsession with the San Andreas is not without reason.

Only three earthquakes in California’s modern record have been as large as magnitude 7.8, and two of them were on the San Andreas — the one in 1906 that destroyed most of San Francisco in shaking and fire, and the Southern California megaquake in 1857, when the region was sparsely populated. A magnitude 7.8 quake produces 45 times more energy than the 1994 magnitude 6.7 Northridge quake.

California’s megafault

Out of the many faults in California, the San Andreas is singularly poised to be the one that unleashes a megaquake in our lifetime.

The San Andreas is the main plate boundary between the mammoth Pacific and North American plates, and is a key dividing line moving southwestern California — encompassing cities including Half Moon Bay, Santa Cruz, Monterey, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles and Anaheim — toward Alaska. The other side, with San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno and Las Vegas, is moving, relatively speaking, toward where Mexico is today.

The San Andreas is by far the fault accumulating seismic strain the fastest in California, making it among the likeliest to rupture in a big way in the coming decades. And it is the longest fault, making it capable of producing the most powerful earthquakes in the Golden State.

Over the course of centuries, the San Andreas fault moves at a breathtaking speed compared with most California faults — the speed at which fingernails grow.

The seismic strain can be detected by GPS satellites — Mission Viejo in Orange County, on the southwest side of the San Andreas, can be seen scooting every year to the northwest, while Twentynine Palms in the Mojave Desert, on the other side of the fault, can be seen moving to the southeast, relatively speaking.

But along most parts of the San Andreas, the ground is not creeping. It’s stuck for long periods of time, and sooner or later, it needs to move in a huge quake to catch up with the rest of the continental plate. On average, there’s about 12 feet of movement per century along the 730-mile San Andreas fault system between Point Arena in Mendocino County and the Mexican border.

The amount of moved earth in a magnitude 7.8 quake can be eye-popping. In a remote section of Desert Hot Springs near Palm Springs, a couple holding hands across the San Andreas during such a megaquake would suddenly be separated as much as 30 feet, almost the entire length of a city bus, Scharer has said.

A domino scenario

But the San Andreas is not the only fault to be worried about.

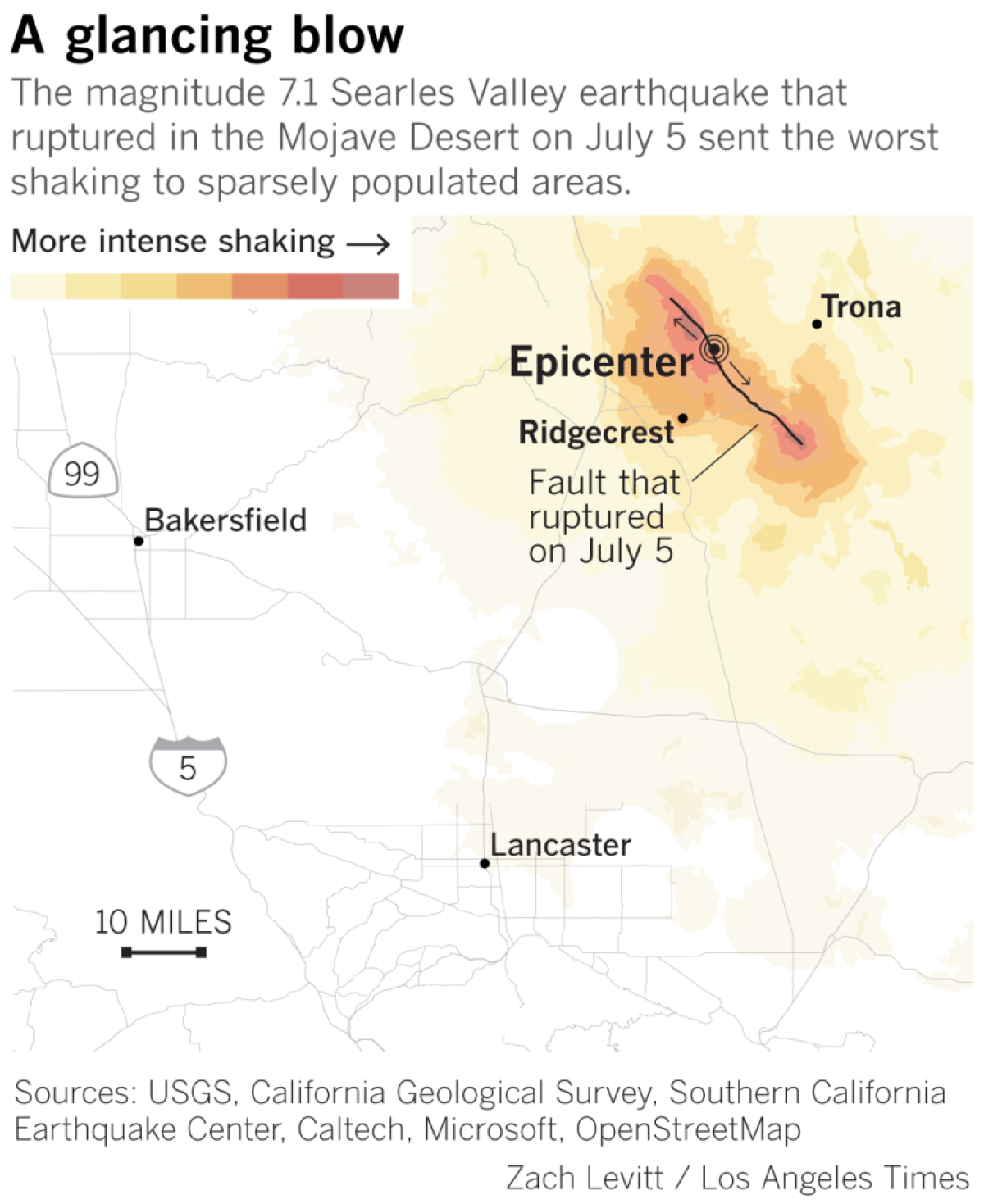

The Ridgecrest quakes occurred in a vast seismic region called the Eastern California Shear Zone, representing a broad swath of the state that includes Palm Springs and the Owens Valley.

Although little known by the public, the zone has been the subject of intense investigation by scientists. It’s home to the only other California quake in the modern record that might’ve been as big as magnitude 7.8 — the Owens Valley quake of 1872, which killed 27 people and destroyed 52 homes.

The Garlock fault is just south of the Ridgecrest quakes, and capable of producing a temblor approaching magnitude 8, directing shaking into Bakersfield and Ventura and Los Angeles counties.

The Garlock fault may be more likely to undergo an earthquake as a result of Ridgecrest quakes, said James Dolan, professor of earth sciences at USC who has spent years studying this region.

The Ridgecrest quakes moved the block of land west of the ruptured fault northwest — away from the Garlock fault. That would have helped unclamp the friction that keeps the Garlock fault still, and makes it easier for it to undergo an earthquake.

No one knows if such an earthquake will actually happen in our lifetime. The Garlock fault can cycle through long periods of hibernation, lasting as long as 3,000 years, Dolan said.

But there are periods in which the Garlock fault is quite active. The last such period was in the centuries around 1500, according to paleoseismic data. And it’s possible that a period of greater earthquake activity began with a quake not very different from July’s Ridgecrest quakes.

It’s plausible that an earthquake on the nearby Panamint Valley fault eventually helped trigger a subsequent earthquake on the Garlock fault. And that, in turn, triggered an earthquake on the San Andreas, according to the study, printed in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth in 2013 and coauthored by Dolan and other scientists at USC, Penn State, Caltech, Utah State and the U.S. Navy.

That sequence of quakes probably didn’t happen within minutes of one another; it may have taken as long as 100 years to complete. But it shows how earthquakes on one fault can lead to a domino effect.

“Every part of the system is mechanically linked with every other part of the system,” Dolan said. “The Garlock acts as a mechanical bridge between the northern Eastern California Shear Zone and the San Andreas.”

Sometimes, it’s smaller but still destructive quakes that are the problem. The magnitude 6.4 Long Beach quake of 1933, the magnitude 6.6 Sylmar quake of 1971 and the magnitude 6.7 Northridge quake of 1994 didn’t occur on the San Andreas, but all caused loss of life.

Triggered quakes

Concern about triggered quakes has undergone closer scrutiny in recent decades.

In 1987, a magnitude 6.2 quake in the Imperial Valley, one of California’s key agricultural areas, near the Mexican border was followed up 11 hours later by a magnitude 6.6 quake with an epicenter six miles away from the first. The so-called Superstition Hills quakes damaged irrigation canals.

The 1992 Joshua Tree-Landers-Big Bear sequence of earthquakes over two months — with successive epicenters roughly 20 miles from one another — raised concerns that the San Andreas was next.

Seismologist Lucy Jones, then with the USGS, remembered rigging up a “go-to-war scenario” where, if a magnitude 6.5 or greater quake occurred in a certain place on the San Andreas, it would trigger an automatic response that included calls to state officials within 20 minutes and a calling out of the National Guard.

The San Andreas was not triggered as a result of that sequence. A significant aftershock did occur seven years later — the magnitude 7.1 Hector Mine quake — but that was in a remote area of desert even farther away from the San Andreas than the biggest quake of 1992.

More recently, seismologists have paid close attention to seismic swarms at the Salton Sea, precariously close to the end of the San Andreas fault. There have been only three times since earthquake sensors were installed there in 1932 that there have been swarms that have particularly concerned seismologists, in 2001, 2009 and 2016. A warning in 2016 led officials to close San Bernardino City Hall for two days. Officials had already planned to close the building within months because of seismic safety concerns.

It’s clear that some people are now quite afraid of earthquakes — understandable, because we can’t see them coming, which makes them scary. But instead of obsessing about exactly when and where they’ll happen, Jones said, we should focus on the risk in the same way we do for car crashes: by being prepared for a disaster that could strike on any day.

“I don’t deal with the freeways in L.A. by wondering if this day is the day for an accident. The reality is, I don’t know which day it’s going to be,” Jones said, which is the reason she wears a seat belt every time she’s in a car.

So do the equivalent for quakes, she said. Get those vulnerable buildings retrofitted. Bolt old homes to their foundations. Secure furniture and picture frames. And stock up on water and food.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.