Trump is cracking down on China. Now UC campuses are paying the price

UC San Diego professor Shirley Meng’s laboratory is a veritable United Nations of research, with 48 scholars from eight countries exploring how to improve battery storage for electric vehicles, robots and — someday — flying cars.

But Meng and her colleagues worry that one country soon will be left out of the lab: China.

For the record:

10:17 a.m. July 24, 2019An earlier version of this post said that professor Shirley Meng’s laboratory had 48 scholars from six countries exploring how to improve battery storage for electric vehicles, robots and, someday, flying cars. The scholars were from eight countries.

The Trump administration has intensified its crackdown over trade, technology and security — and now it has spread to America’s vaunted universities, turning the University of California into an especially big target.

UC campuses from San Diego to Berkeley are reporting that Chinese students and scholars are encountering visa delays, federal scrutiny over their research activities, and new restrictions on collaboration with China and Chinese companies.

The National Institutes of Health, a major source of university research funding, also has raised questions about current and former scientists at UC’s Berkeley, Los Angeles, Riverside, San Diego and San Francisco campuses, prompting reviews of whether they followed federal grant rules, including confidentiality requirements and disclosures of outside support.

The overarching fear is that Trump’s crackdown will drive away top Chinese scholars and jeopardize the kind of open international collaboration that has been a hallmark of higher education in the U.S., contributing to world-class research and scientific progress.

Federal officials warn that China is exploiting America’s open academic environment to steal intellectual property and innovations.

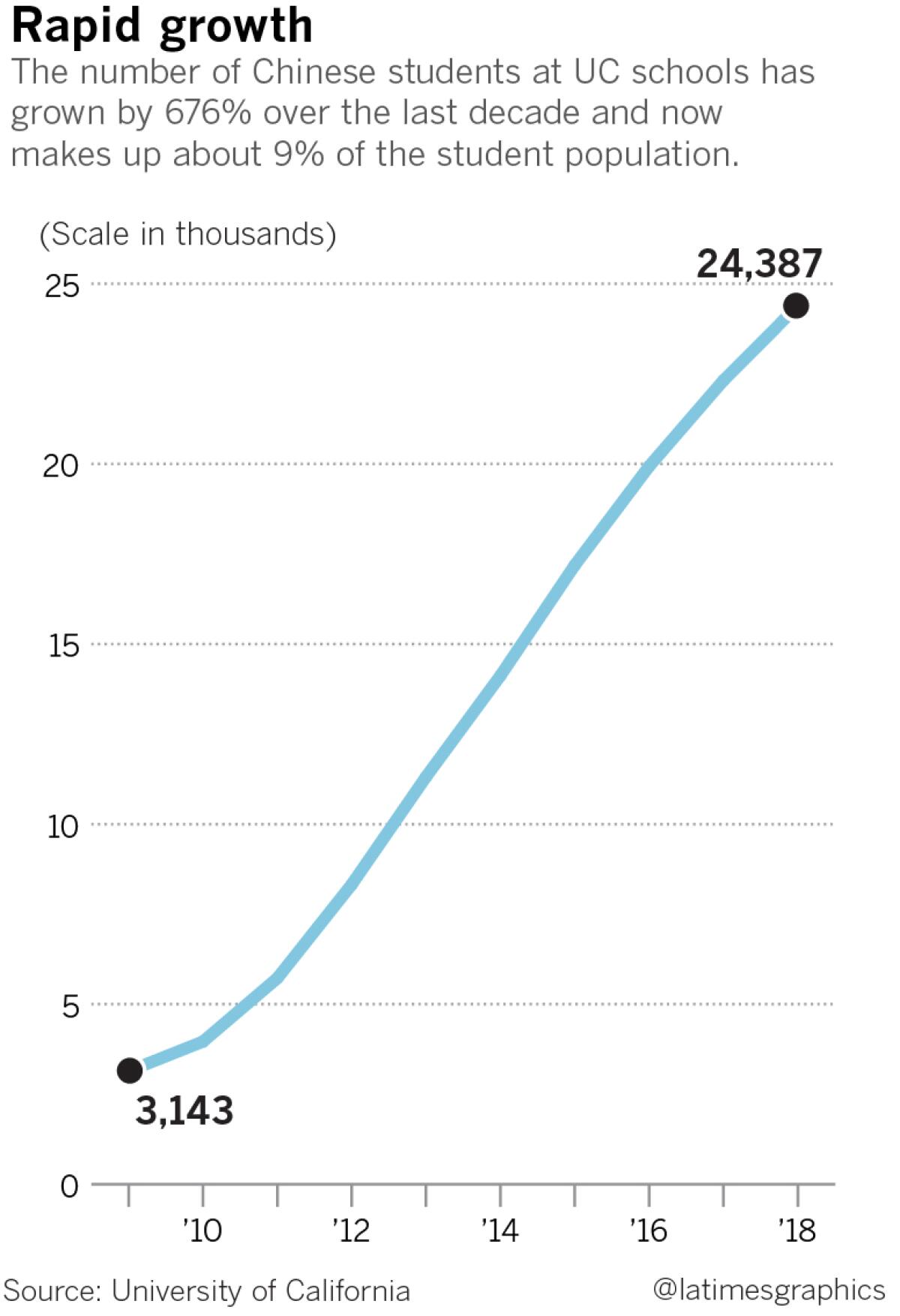

The UC, with its Pacific Rim location and cutting-edge research supported by billions of dollars in federal grants, is in the crosshairs because it has the largest number of Chinese students and scholars in the United States.

So far, no UC campus has moved to dismiss Chinese scholars — unlike Emory University in Atlanta and M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Texas. But a UC San Diego scientist from China recently resigned after the campus put him on leave while it reviewed whether he had disclosed all outside funding and contacts, a university official confirmed.

And Meng, for the first time ever, has warned her students to think twice about going home to China this summer because tougher visa policies could significantly delay their return to the United States and impede their research.

“Constantly, my students are hearing stories of someone getting stuck in China for months,” she said. “In the past, we didn’t have this kind of bad news everywhere.”

Switch in federal policy

University leaders are scrambling to understand the federal government’s new approach even as they try to balance the tradition of openness in U.S. higher education with concerns about national security and economic competitiveness.

“Obviously we have to be careful to protect our intellectual property, and I realize there are legitimate concerns about China’s practices,” said UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ. “But nonetheless, I think the world has so much more to profit by the sharing of research than putting up walls.”

On Thursday, UC’s Board of Regents approved plans for a systemwide audit to identify risks related to “foreign influence.” They include reviewing all grants to assess compliance with federal rules and identifying categories that may be susceptible to problems. UC President Janet Napolitano has asked campus leaders to establish greater safeguards around international research and visitors.

Chinese espionage and intellectual property theft are longstanding American concerns, but the Trump administration’s tougher line on China reflects a broad rethink of U.S. policy toward Beijing. It has switched from engagement to confrontation.

In December 2017, the White House’s National Security Strategy put China in the same camp as Russia, accusing Beijing of “attempting to erode American security and prosperity” by, in part, stealing proprietary technology and innovations.

FBI Director Christopher Wray also declared that universities need to wake up to the China threat. His agency has bulked up its staff focused on China, and has been holding meetings with university research leaders.

Lawmakers on both sides of the political aisle have been ringing alarm bells, too. Congress passed measures that could cut off federal funds to universities deploying certain Chinese equipment. Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and other China hardliners have urged universities to break ties with the Confucius Institute, a Beijing-funded language program that exists on many U.S. campuses. They also have proposed China-related measures that could affect academic grants and researchers.

University leaders are worried that a patchwork of new restrictions could cause confusion and chill research, and so have backed a bill that would establish an inter-agency working group to coordinate efforts to protect federally funded research.

Robert Daly, director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States at the Woodrow Wilson Center, said the crackdown presents a quandary for Americans.

“This openness in academic freedom is absolutely a core American value. But security is a core American value, too,” he said. “So China’s rise is pitting core American values with each other in ways we haven’t faced before.”

Graduate students

U.S. intelligence officials are mostly concerned with graduate students, who made up about a third of some 365,000 Chinese nationals at U.S. universities last year, as well as researchers and professors who lead research.

At UC, Chinese students numbered 24,387 in fall 2018 — 53% of all international students — and a quarter of them were graduate students.

UC San Diego was the most popular campus for Chinese students, enrolling 5,296 last year. The campus also has the largest number of social scientists studying contemporary China among universities in North America. As a result, the Trump administration’s crackdown has caused particular concern there.

In recent months, several UC San Diego scholars have ended their participation in China’s academic talent recruitment programs. China sponsors about 200 such programs to offer scholarships and otherwise lure academics to China to do research and start businesses.

Federal officials are worried that scholars — most of them Chinese nationals — will leave the U.S. with research and use it to benefit China’s military and industry. Then China would “outbid, outsource and outcompete U.S. companies,” according to one U.S. counterintelligence official.

“It’s institutionalized theft,” the official said.

In January, the U.S. Department of Energy announced it would ban employees and grant recipients from participating in talent programs run by “sensitive countries” — widely assumed to be China. The NIH, however, said it has no plans to defund universities whose researchers are participating.

Sandra A. Brown, UC San Diego vice chancellor for research, said federal officials have made clear the stakes are high for her campus, where federal dollars account for two-thirds of its $1.2-billion research enterprise.

The campus held three town halls in May to answer questions from faculty about federal rules on grants and travel. “My main message was that we will continue to be open,” Brown said. “Our own faculty should continue to do research with the best colleagues in the world.”

At UC Berkeley, administrators also are scrambling to inform faculty about the heightened enforcement of federal grant rules. Randy Katz, vice chancellor for research, said campus officials are investigating one scholar flagged by the NIH to determine whether all funding sources — foreign and domestic — were properly reported.

In the past, Katz said, it was not clear that federal agencies wanted such detailed reporting, so Berkeley never really required it. But last August, NIH Director Francis Collins said some researchers were failing to disclose substantial payments, diverting intellectual property and sharing confidential information with foreign governments. That could create conflicts of interest if, for instance, China obtained access to files for a patent from research supported by the NIH.

“I have instructed faculty to be as transparent as they can and err on the side of telling federal agencies everything,” Katz said.

Some fear the heightened scrutiny could cripple global scientific collaboration.George Blumenthal, an astrophysicist and former UC Santa Cruz chancellor, said China is critical to an international project to build the largest visible-light telescope in the world — and could back away from its substantial financial commitment if Chinese scholars cannot be assured of access to the project in Hawaii.

Scholars note that nearly all university research is unclassified, published and open to all. But Susan Shirk, a leading China expert with UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy, said federal officials are expected to issue new controls this summer to substantially broaden the bans on transferring or disclosing information outside the United States.

Meng fears that her research area of battery storage could be included. “I cannot emphasize enough that, for growth and expansion of [electric vehicles], the whole world has to work together,” she said.

Visas

For many Chinese students, the biggest worry is the tightening of visas.

Shunda Chen is a UC Davis postdoctoral student in physical chemistry and nanomaterials, studying ways to convert wasted heat into useful energy. After earning a doctorate at Xiamen University in his native China, he followed his current research leader to UC Davis in 2015. Chen said he doesn’t dare take trips outside the United States now.

The U.S. government does not publish information on visa denials. But the number of F1 visas — the primary type of student visas — issued to China fell by 13% between fiscal 2017 and 2018, compared to an 8% decline for all countries, according to an analysis of State Department data by the nonpartisan National Foundation for American Policy.

Since last year, under a policy pushed by Trump adviser Stephen Miller, some Chinese students researching certain sensitive subjects have been limited to one-year visas. China has taken note. Last month, China’s Ministry of Education issued a public warning about restrictions on visas to study in the United States.

And denial rates for H-1B temporary employment visas have risen significantly in the last two years, making it difficult for students from China and other nations to stay and work in the United States.

Trump’s comments about China have offered little clarity. About a year ago, he reportedly said most Chinese students in the U.S are spies. But last month, Trump spoke of making it easier for Chinese students to get green cards under a “smart person’s waiver” program.

So far, only UCLA and UC Berkeley — of the UC system’s nine undergraduate campuses — have seen a slight dip in international student freshmen applications for fall 2019. Overall, the number of Chinese students enrolled at UC campuses increased in 2017-18 over the previous year.

Meng said her Chinese doctoral students chose to stay because the U.S. system of meritocracy allows them to advance more equitably than in China, where there is a greater focus on guanxi, or connections.

Still, American universities are bracing for a decline in Chinese students, who typically pay full tuition . At San Francisco State University, Chinese freshmen applications have declined by about a third in the last two years.

“If they are excluded there is no replacement,” said Shirk, of UC San Diego.

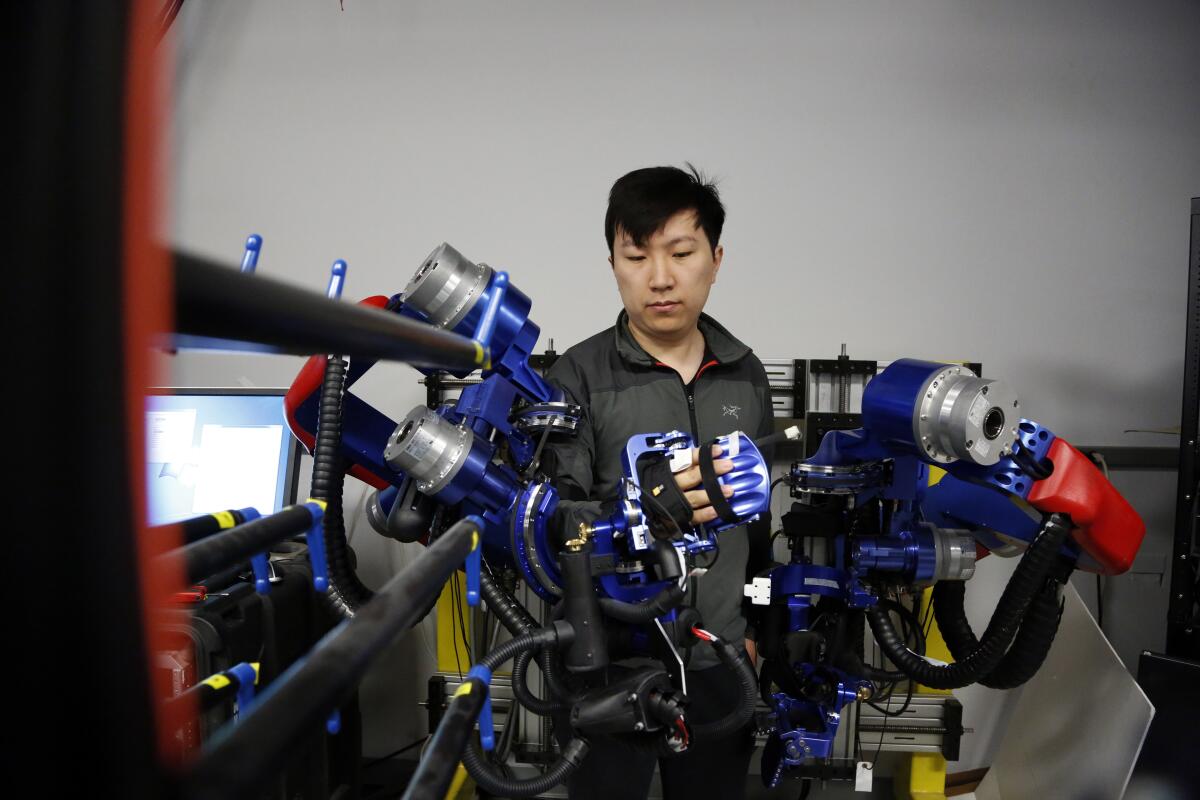

Yang Shen is a case in point. A graduate of one of China’s top schools for mechanical engineering, Shen has been a key member of the UCLA Bionics Lab, which is developing robotic “exoskeletons” to help stroke victims reactivate their neural connections.

Shen said Chinese students want to study with the best. But there are other options if visas become more difficult to obtain, including pursuing graduate studies in France, the United Kingdom, Singapore, Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia.

“I do feel there might be a tendency to not easily stay here,” said Shen, who completed his doctorate in robotics last month. “But as long as I’m contributing to society, it’s fine.”

Twitter: @TeresaWatanabe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.