California Politics: When voters don’t care about the election

Perhaps it’s because California is such a sprawling nation-state, where powerful political groups routinely spend tens of millions of dollars on high-profile campaigns, that we fail to recognize the more granular reality that in so many contests — most notably special elections — the outcome is decided by an astonishingly small subset of voters.

It’s a political axiom in the state that held true again this week in four special elections for seats in the Legislature and Congress. In each case, voter turnout was so low that if a comparable number of people had attended a big football game in California, there would have been plenty of empty seats in the stadium.

And if that’s the strong shot of whiskey, here’s the chaser: Three of this week’s special elections ended without a candidate winning the job. Those communities will now have to hold a second special election — another unplanned expense picked up by taxpayers — where turnout isn’t likely to be much better.

Four special elections, one winner

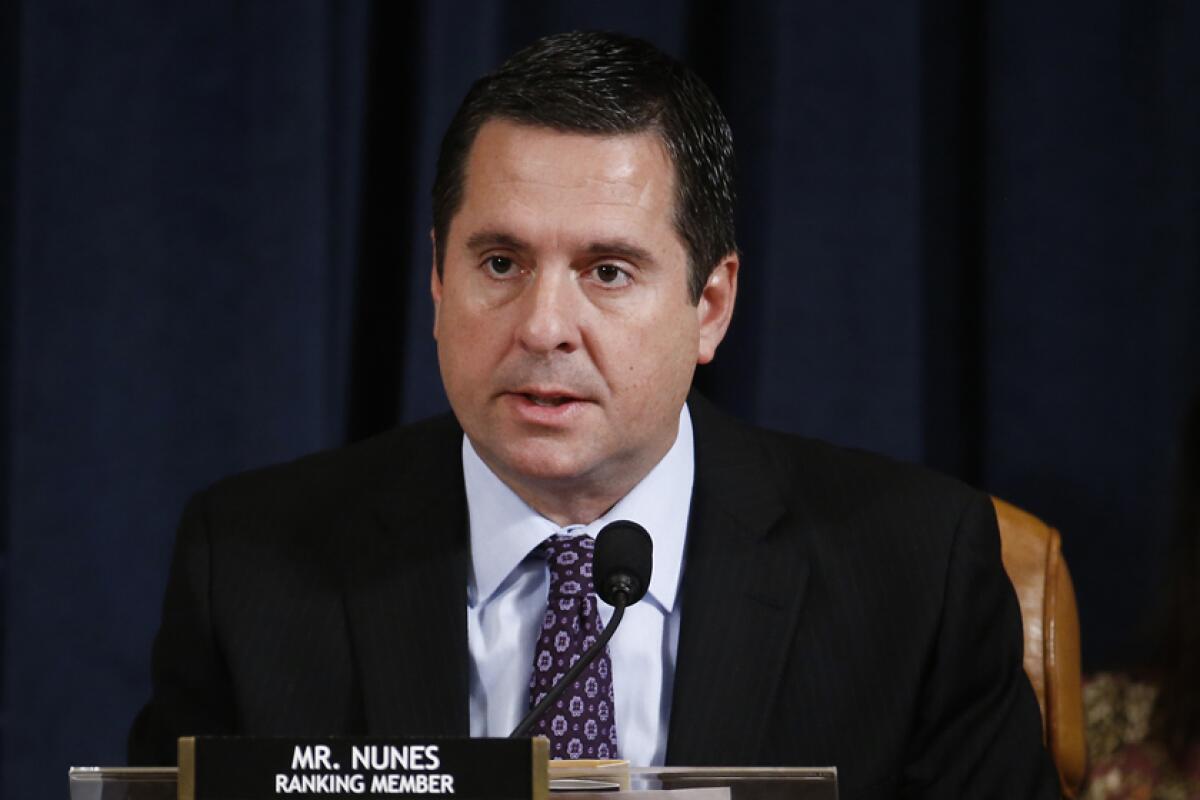

Elections were held Tuesday to fill three seats in the state Assembly, left vacant as part of a historic exodus from the Legislature, and an election to fill the unexpired term of former Tulare Rep. Devin Nunes.

The lone winner was Lori Wilson, the mayor of Suisun City who was elected in an Assembly district that stretches to the east of San Francisco Bay. She will replace former Assembly Member Jim Frazier, who resigned in December. Wilson, a Democrat, will probably take office next week and becomes the front-runner in November’s contest for a full two-year term.

In a district with more than 300,000 registered voters, the unofficial tally shows that Wilson was elected with fewer than 27,000 votes. And while some observers may point out that Wilson was running unopposed, that’s not enough to explain the voter apathy.

Tuesday also saw a special election in Los Angeles County to fill the seat left vacant by former Assembly Member Autumn Burke in representing communities from Inglewood to Venice. Even fewer voters showed up than for the race up north — less than 22,000 votes tallied as of Thursday — and none of the four Democratic hopefuls secured a majority, forcing a runoff in June.

The results were a little better in San Diego County, where early returns show less than 14% of voters cast ballots in the special election to complete the term of former Assembly Member Lorena Gonzalez. Here, too, a runoff election will be held between the top two candidates, both Democrats.

And a runoff is in the cards in the Central Valley to replace Nunes, who resigned in January. The race between a half-dozen candidates for a brief stint in the House of Representatives looks to have drawn the highest turnout of Tuesday’s special elections — almost 64,000 votes in early returns. But that’s still only about 15% of the district’s registered voters.

Why hold so many special elections?

The election to replace Nunes merits special mention because the Republican firebrand, who resigned to run former President Trump‘s social media company, could have saved taxpayers some money if he had simply chosen to delay his departure by about nine weeks. Under California election law, that would have made a special election optional.

That might have been the most practical course of events, given the big changes made to Central Valley congressional districts by the California Citizens Redistricting Commission.

Nunes’ seat will largely disappear, with his home drawn into a new district with House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and many of his other communities scattered across other districts, some that will favor Democrats. The top vote-getter in Tuesday’s special election, former state Assembly GOP Leader Connie Conway, has acknowledged she’d largely be a caretaker for a district that will vanish after November’s regularly scheduled election.

The three legislative contests, however, were unavoidable.

State law gives requires a special election unless a legislative vacancy occurs after the formal filing period for the next election. Not that everyone thinks that’s a good idea, especially given that special election costs are almost entirely borne by local governments.

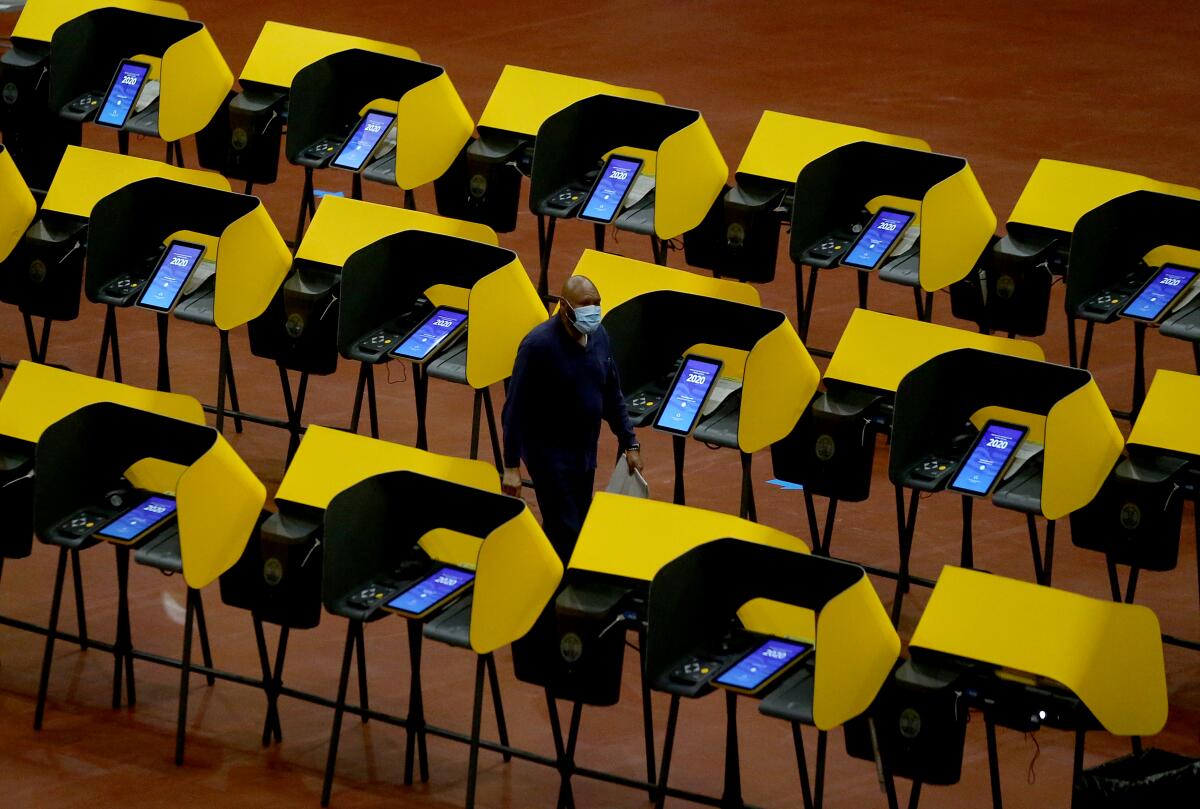

And though low turnout in special elections might have been expected in years gone by, with voters perhaps too busy to swing by a polling place, it’s important to remember that every voter now can cast a ballot from home. The pandemic led to a sweeping change in state law that now requires ballots to be mailed to every active voter.

The sharp uptick in recent years of special elections in California — there have been 22 just since the spring of 2018 — has led to calls for a change. The most talked-about idea would require the governor to appoint an interim lawmaker if the vacancy occurred in the home stretch of the lawmaker’s term in office. But in 2014, a bill to do that fizzled in the state Capitol, largely killed by legislators who had won office through — wait for it — a special election.

There will be one more stand-alone special election this year, when San Francisco voters head to the polls on April 19 for a runoff to fill the Assembly seat formerly held by City Atty. David Chiu.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

NFTs: the next thing in campaign cash?

It was probably bound to happen that political campaigns would be drawn into the realm of cryptocurrency. And so California’s campaign watchdog agency has offered some early thoughts about when and how one of the hottest digital assets should be treated as a financial boost to a candidate’s election.

Last week, California’s Fair Political Practices Commission issued a six-page opinion on how campaigns should report the profits from selling non-fungible tokens, widely known as NFTs.

The question was raised by Teddy Kapur, a candidate for Los Angeles city attorney. The Democrat’s campaign has told state officials that it wants to hire a vendor to create NFTs and sell the items to help Kapur best a seven-candidate field in the June 7 election. But unlike some NFT transactions, the Kapur campaign told state regulators that it will sell the tokens for a fixed price and that it won’t have any financial stake in the “trading or reselling” of the Kapur tokens.

The short answer from FPPC officials seems to be: the sale of NFTs are allowable as long as existing contribution rules are followed. In the opinion letter signed by FPPC Chairman Richard Miaidich, Kapur’s campaign was told the items should be treated the same way as food or souvenirs offered to anyone who buys a ticket to attend a political fundraising event.

Token sales, Miadich wrote, “are reportable contributions and the individuals that purchase NFTs are the source of those contributions.”

Spring recess in Sacramento

Legislators adjourned Thursday for a one-week spring recess after weighing in on scores of bills in policy committees this week. They will reconvene on April 18 for a rush of work, with all fiscal bills (also known as proposed laws that would cost money) having to clear their first big policy committee deadline by the end of the month.

Next week, The Times will take a closer look at some of those bills. We’ll also be tracking tax payments as April 15 approaches with an eye on the potential size of another multibillion-dollar state budget surplus.

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.