Meet David Sacks, Gavin Newsom’s loudest critic in Silicon Valley

The millionaires and billionaires of California’s tech industry have become reliable donors to Democratic politicians in recent decades, and most cash flowing from Silicon Valley into 2021’s recall race has gone to oppose the recall and support Gov. Gavin Newsom.

But a handful of tech investors and entrepreneurs rank among the top donors to the recall cause, alongside Orange County conservative organizations and real estate moguls from across the state.

The largest pro-recall tech donors have stayed quiet about their support and did not respond to requests for comment from The Times. Some, such as Accel Partners co-founder Dixon Doll and Doug Leone of Sequoia Capital, are longtime backers of Republican candidates and causes.

Others have less of a track record of mixing it up in politics. The investor and SPAC billionaire Chamath Palihapitiya donated $100,000 to the signature-gathering effort in January, then publicly flirted with the idea of running to replace Newsom, only to back away from the idea by early February — and largely drop the topic altogether in the months since. Justin Kan, the founder of Twitch who now runs the fund Goat Capital, threw a little over $36,000 into pro-recall PACs this year but has also stayed mum in public.

But one boldface name from the venture capitalist class has not only poured his own money into the cause but also used his many platforms — from tweets and blog posts to television appearances and multiple podcasts — to beat the drum for replacing Newsom, even as the campaign appears to be flagging in the polls and most of his allies in Silicon Valley have fallen away.

For David Sacks, it’s just the latest in a long series of assaults on the establishment.

The 49-year-old venture capitalist made his first fortune as a member of the “PayPal Mafia” — the group of entrepreneurs and executives, including Peter Thiel, Elon Musk and Reid Hoffman, who launched the payments processing company and sold it to EBay — before going on to start and run a number of successful software companies and co-found a VC fund, Craft Ventures, which now has $2 billion under management.

By late August, Sacks and his wife, Jacqueline, had together donated $90,000 to pro-recall committees. On Sept. 2, after a new poll showed the recall effort struggling with 58% of likely voters opposing it, Sacks donated an additional $50,000 to the campaign.

Sacks did not respond to requests to speak with The Times for this article, but he has voiced his thoughts on the recall push in numerous public statements. Despite having donated over $58,000 to Newsom’s election campaign in 2017, he believes the governor has failed to rise to the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and to address issues such as crime, homelessness, fire management and the promotion of business in the state.

Earlier in the summer, on the podcast he co-hosts with Palihapitiya and two fellow venture capitalists, Jason Calacanis and David Friedberg, Sacks said that no clear replacement for Newsom had emerged but that he thought the two Republican Kevins — Faulconer, a former San Diego mayor, and Kiley, an Assembly member from Placer County — could be good options.

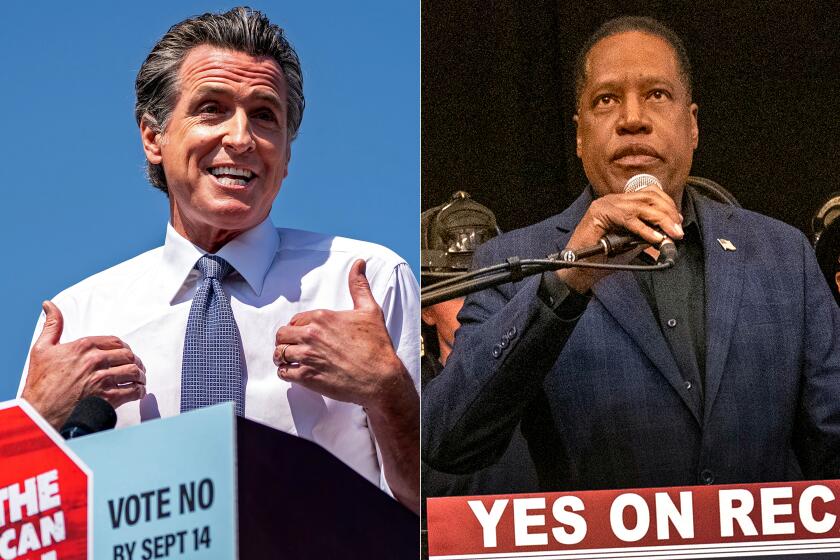

Now that polls have talk radio host Larry Elder as the leading replacement candidate, Sacks has made clear that he believes a successful recall, regardless of the new governor, is a necessary symbolic gesture to send a message to the state’s political class.

Silicon Valley has always had its share of Republicans and libertarians, with the PayPal network making up its center of gravity in recent years. But since the pandemic, this group has been increasingly energized around the idea that California is fatally broken. Some big investors and founders have relocated their companies and/or personal residences to Texas or Florida, while others, such as Sacks, have dug into statewide and local politics in the Bay Area.

This isn’t Sacks’ first brush with politics. He got his start in the arena during his school days at Stanford, where Sacks wrote and edited for the Stanford Review, the conservative publication started by friend and mentor Thiel in 1987. The Review was animated by the campus culture wars of the 1980s and ’90s, opposing political correctness, defending the Western canon from attempts to diversify it and ringing the alarm bell about alleged feminist overreach.

In the publication’s “Rape Issue,” Sacks wrote in defense of a Stanford senior accused of rape, opining that the victim had not resisted and that statutory rape itself was a phony crime, “a moral directive left on the books by pre-sexual revolution crustaceans.” He and Thiel also found a cause celebre in Keith Rabois, a Stanford law student who had stood outside the home of a lecturer and screamed a homophobic slur followed by “Hope you die of AIDS!”

From Ron Conway and Marissa Mayer to Doug Leone and David Sacks, these are the biggest tech industry donors to California’s gubernatorial recall race, for and against.

Rabois, who went on to work at PayPal and is now a general partner at Founders Fund, the VC firm that Thiel co-founded in 2005, did not face any disciplinary consequences, but he was publicly reprimanded by school officials. Sacks and Thiel framed the school’s response to Rabois as an outrageous example of censorship, and they included the episode and their takes on campus rape in a book they co-wrote after Sacks’ graduation in 1994, “The Diversity Myth: Multiculturalism and Political Intolerance on Campus.”

When journalists who were digging into Thiel as he emerged as a major Trump supporter in 2016 found the book’s segment on date rape, which the authors liken to “seductions that were later regretted,” Thiel and Sacks apologized. Sacks told tech journalist Kara Swisher that “this is college journalism written over 20 years ago. It does not represent who I am or what I believe today. I’m embarrassed by some of my former views and regret writing them.”

When the book was published, however, Thiel and Sacks both went on the conservative opinion circuit, following the path from campus conservative to commentator blazed by William F. Buckley Jr. and Dinesh D’Souza before them. Sacks and Thiel mocked the idea of Indigenous Peoples’ Day in the pages of the Wall Street Journal, wrote against affirmative action in Stanford Magazine and appeared on Buckley’s “Firing Line” to discuss the ills of multiculturalism in January 1996.

Sacks stayed close with the Stanford Review set over the years, joining Thiel, Rabois and other alumni at PayPal, building out a business network that has built or invested in a disproportionate share of the leading companies in Silicon Valley: Tesla, SpaceX, Yelp, YouTube, Square, Palantir, Facebook, LinkedIn, Airbnb and Uber, among others, are all linked to the group.

But as Max Chafkin, a features editor and tech reporter at Bloomberg Businessweek, notes in his forthcoming book on Thiel and his network, “The Contrarian,” the politics came first.

“It’s important to say that the genesis of the PayPal mafia is a political network, not a business network: It’s the Stanford Review,” Chafkin said. “This political project has been integral to the development of the tech industry as it exists today.”

Chafkin sees the campus politics laid out by Sacks and Thiel at work across the industry, including PayPal’s original mission (Thiel told Wired in 2001 that he saw anonymous electronic money transfers as a key to geopolitical liberation “and the erosion of the nation-state”), Facebook’s long-standing laissez-faire approach to speech on its platform and Uber’s dismissive approach to labor law and taxi regulation.

The success of the group’s businesses has served to strengthen its political clout, as well. “It’s a club, and being part of that club is valuable, and part of membership in that club is political affinity,” Chafkin said.

In the last five years, as the group’s wealth has grown and state and federal regulators are starting to look more closely at the business practices of the major tech companies they’ve helped create, the PayPal mafiosi have grown more vocal in their politics — and started flexing their bank accounts.

Sacks’ political donation history is small compared with Thiel’s, who donated around $1.5 million to support Trump in 2016 and is putting $10 million behind the campaigns of two Republican proteges running for Senate in 2022 — Ohio’s J.D. Vance, who worked at Thiel’s Mithril Capital and started a new fund in 2019 with money from Thiel and other investors, and Arizona’s Blake Masters, who followed Thiel’s path through Stanford undergrad and law school and runs Thiel Capital, another of the billionaire’s investment firms.

Until 2016, Sacks was a reliable Republican donor, pitching in roughly $80,000 to candidates and party committees over the course of the last 20 years. In 2016, he gave $28,000 to the Democratic National Committee and over $5,000 to Hillary Clinton’s campaign, followed by 2017’s whopping $58,400 to Gavin Newsom and a $10,000 donation to the Democratic midterm fund in 2018.

But the pandemic seemingly brought an end to his Democratic support. Besides the recall effort, Sacks has also paid into and promoted the efforts to recall members of the San Francisco school board, San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin and Boudin’s L.A. County counterpart, George Gascón, and has donated to a statewide political committee, Govern for California, that has backed a number of Republican candidates for state seats in recent election cycles.

In 2021, Sacks finds himself standing athwart history in Silicon Valley without his fellow PayPal dons. Thiel officially moved to Los Angeles and multiple other mansions throughout the globe in 2018 and has been focusing on federal races.

Rabois spent most of 2020 rabble-rousing against California’s COVID-19 restrictions and hyping up freewheeling Miami as the new destination for tech. He made good on his promise in December with the purchase of a $29-million house on San Marco Island in Miami Beach.

Although Sacks may be alone in California politics this round, that doesn’t mean he’s out of the club. Just a few months after Rabois moved to Florida, property records show, he gained two new neighbors on the artificial islets of Miami Beach: Thiel and Sacks.