Ring tapped a network of influencers to promote its cameras. They were LAPD officers

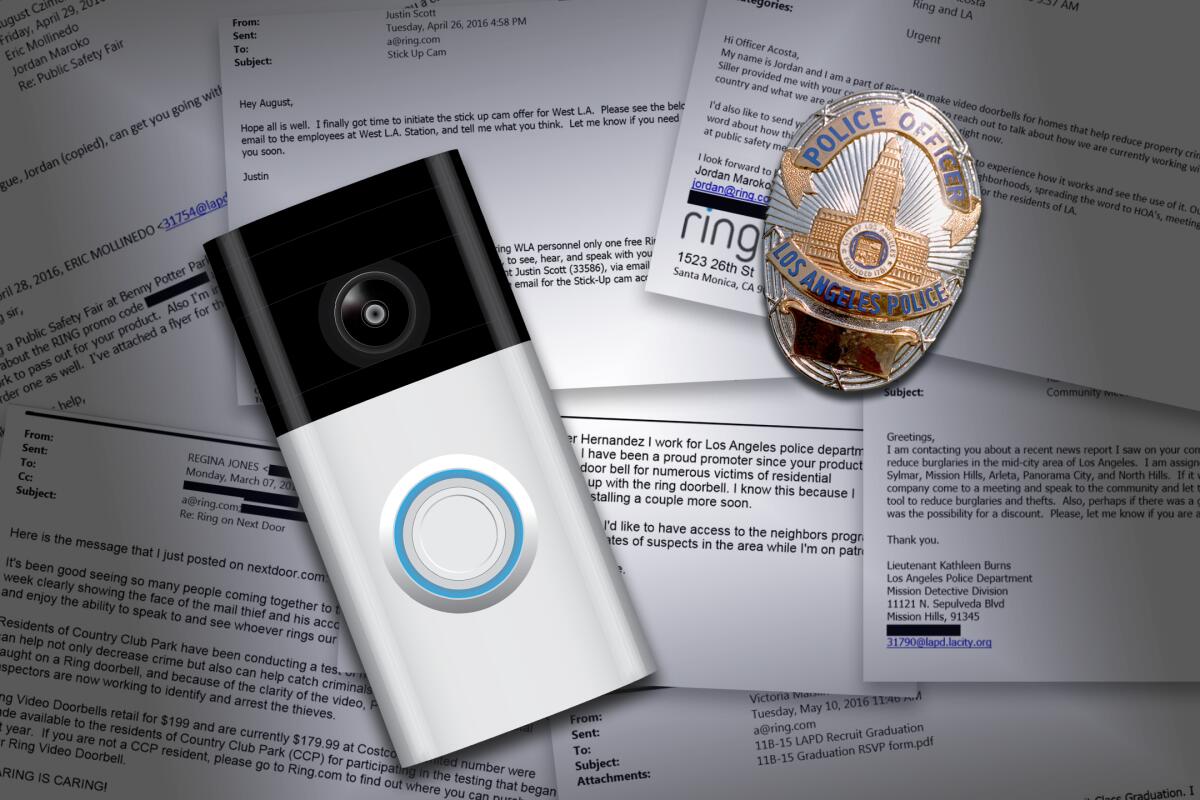

In a bid to bolster its claims as a crime-fighting tool, Ring deployed a tactic popular in the business world: influencer marketing. It selected a cadre of brand ambassadors, rewarded them with free gadgets and discount codes, and urged them to use their connections to promote the Santa Monica security camera startup via word of mouth.

In this case, the brand ambassadors were Los Angeles Police Department officers.

“You are killing it, by the way. Your code has 14 uses, eleven more and I will be sending you every device that we sell,” a Ring employee wrote to one officer in a 2016 email. “Do you have any community meetings or crime prevention fairs coming up?”

Ring provided at least 100 LAPD officers with one or more free devices or discount codes and encouraged them to recommend the company’s web-connected doorbells and security cameras, emails reviewed by The Times reveal. In more than 15 cases, emails show that officers who received free gadgets or discounts promoted Ring products to fellow police officers or members of the public.

For Ring, turning police into brand ambassadors helped spur the adoption of Ring doorbells while lending credibility to the company’s claims that it was an effective crime-reduction solution.

In return, participating officers got tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of free and discounted electronics and helped establish a network of personal surveillance cameras that the LAPD could tap into with much less red tape than the typical means of obtaining video.

The practice, privacy and criminal justice experts warn, raises the question of whether LAPD officers were serving the public in their interactions with Ring, or if they were serving a private business and themselves.

LAPD rules restrict the acceptance of gifts that could be seen as an attempt to influence the actions of officers. After a preliminary review of the emails, the department said officers did not appear to have violated agency rules.

An agency spokesperson said that although accepting free devices and personally recommending those products to community members did not violate the LAPD code of ethics, a paid endorsement would run afoul of agency rules.

“Of course, each situation is looked at on a case by case basis,” Det. Meghan Aguilar, a spokesperson for the LAPD, said in a statement. “If there is something brought to the department’s attention which appears to be misconduct, it will be referred to Professional Standards Bureau for investigation.”

It’s unclear whether LAPD officers disclosed their arrangements with Ring to the public or fellow officers.

Ring ended its law enforcement ambassador program, called Pillar, in 2019 and now works directly with community organizations, said Emma Daniels, a spokesperson for Ring, which Amazon acquired in 2018.

“Ring stopped donating to law enforcement and encouraging police to promote our products years ago,” Daniels said in a statement. “As Ring has grown, our practices have evolved, and we are always looking for ways to better serve our customers and their communities.”

The Times reached out to each officer named in this story directly or through the union and the Police Department and did not receive any response by the time of publication.

Tony Cheng, an assistant professor at UC Irvine’s Department of Criminology, Law and Society, warned that the public probably would be unable to make a distinction between a personal recommendation from an officer who received a free or discounted Ring product and a paid endorsement. “That seems to be splitting hairs,” Cheng said.

The practice, he said, is a cause for concern both substantively and symbolically — freebies from private companies could give officers motives other than public service, and they could give the public the impression that recommendations from officers can’t be trusted.

“We don’t want to be put in the position to have to question or be skeptical about the quality of public safety advice that they’re giving out in meetings, for example, which could be compromised by these private partnerships,” Cheng said.

Courting officers

The brand ambassador model is simple. Give free merchandise to influential individuals, and turn them into a low-cost marketing team.

Some brands court celebrities with huge followings; others look to people who aren’t necessarily famous yet have influence in their own communities. A makeup artist with a social media presence might receive swag for posting about new eye shadow palettes. A runner might get free shoes for talking about footwear on Facebook. And stylish Instagram users might land freebies if their feed has the right look.

It’s less common, however, for public servants to participate in the brand ambassador model.

Ring began its outreach to the LAPD during a period of growth. Founded in the Pacific Palisades garage of Jamie Siminoff in 2012, Ring was proving wrong critics who had doubted the startup during an appearance on the TV show “Shark Tank.” As e-commerce took off and concerns about porch theft rose with it, consumers embraced Ring and other video doorbells. By 2016, the company had an estimated $155 million in sales, commanding 80% of the global video doorbell market. It was valued at $460 million and had amassed $209 million in venture capital funding, and Siminoff, at the time, was eyeing a potential initial public offering of stock.

But Ring wasn’t profitable. The company was also having trouble proving definitively that its products helped reduce crime in neighborhoods — a marketing promise it sought to validate by working with the LAPD, among other police departments.

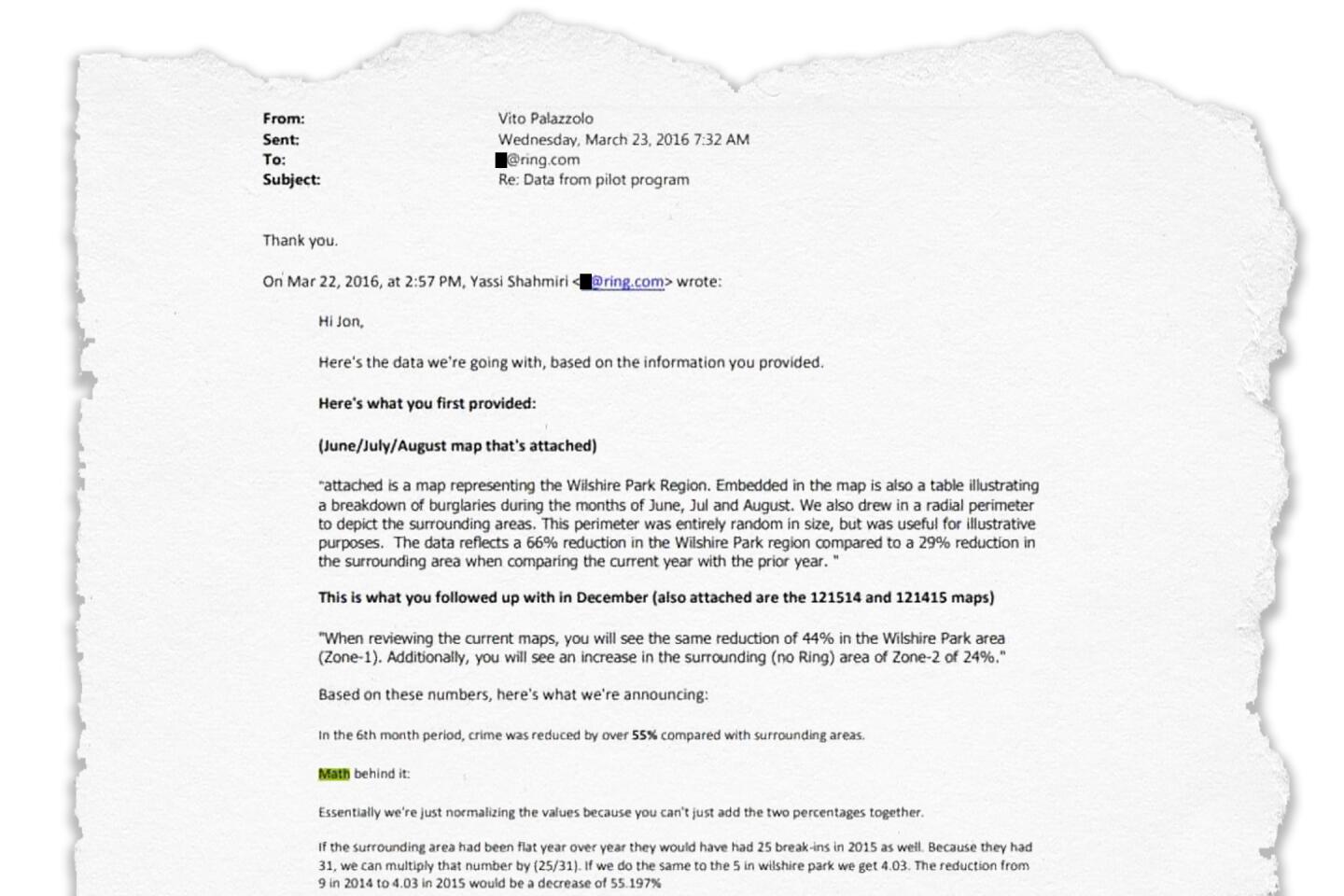

Emails from 2016 reviewed by The Times and released via a public records request show that Ring deployed a standard playbook as it approached officers across LAPD stations.

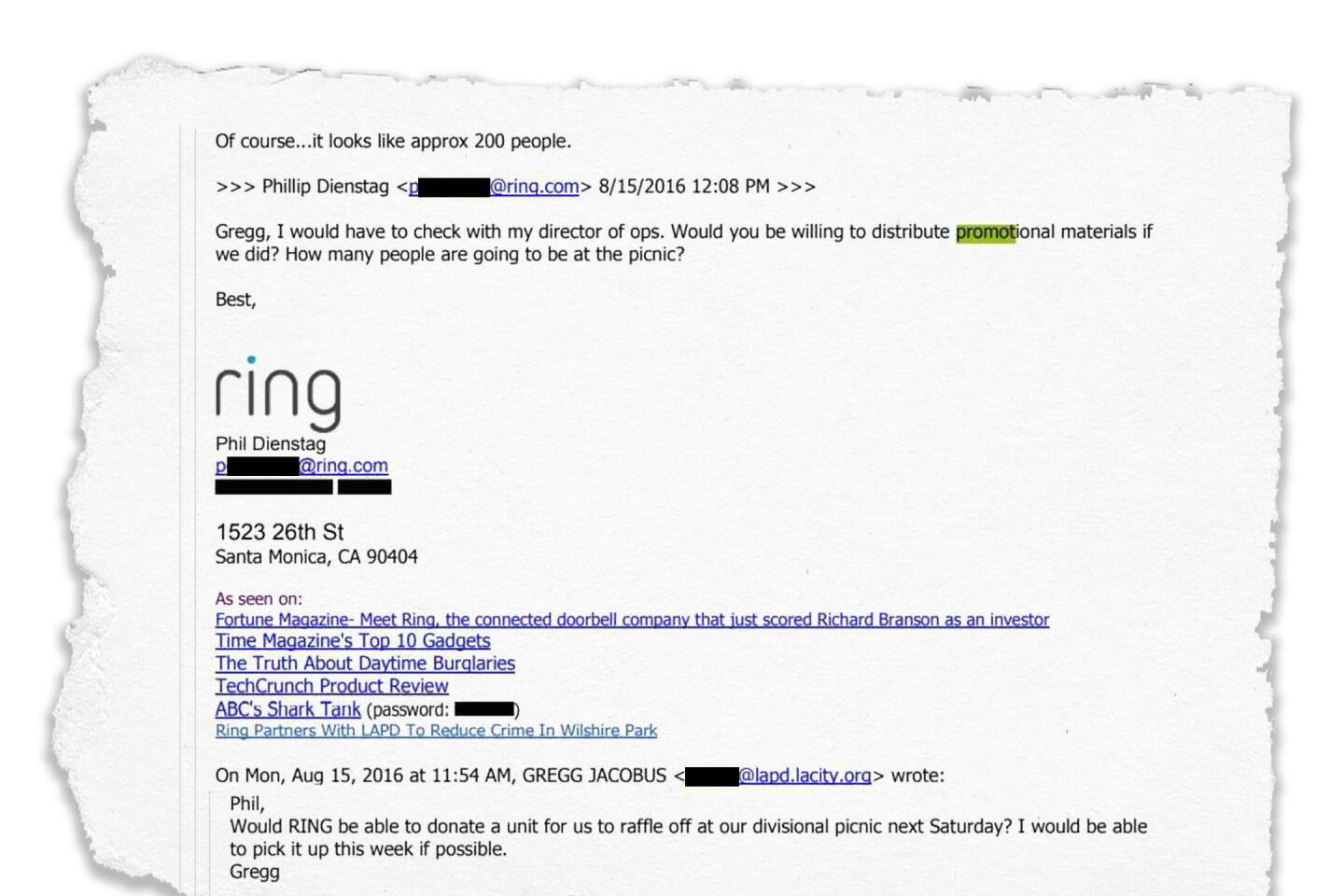

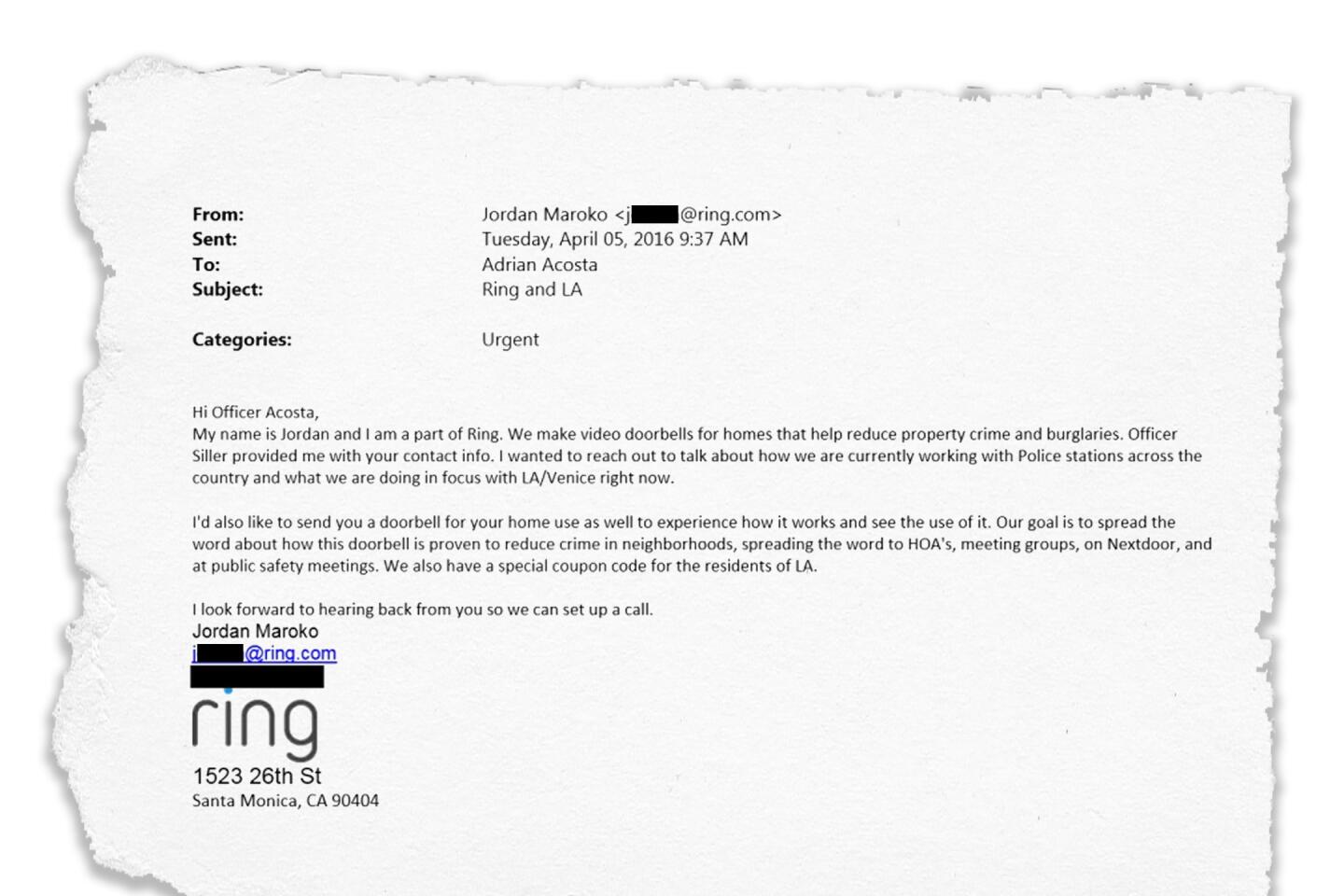

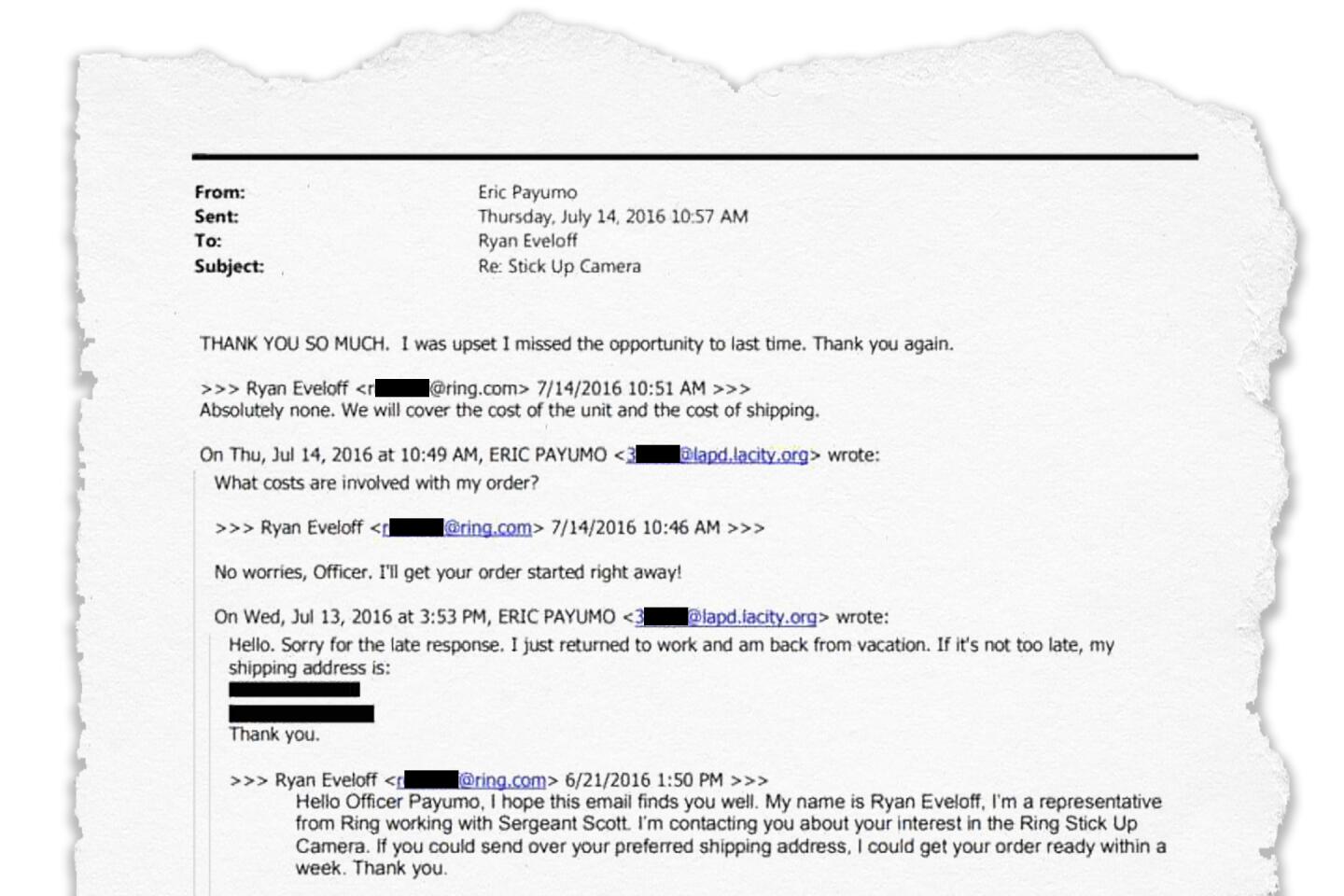

Often, Ring would make contact with an officer at an event or through introductions from fellow police. Then came a follow-up, with a request for a phone call to discuss ways to “reduce crime” in their neighborhoods. Finally, Ring thanked the officer for the call and said a free product was on its way.

In at least 24 cases, Ring emailed a discount code and encouraged an officer to share it with colleagues, prominent local individuals such as heads of neighborhood associations and residents of the communities they police.

Ring’s goal when sending free devices to officers was to let them experience it so they could “spread the word about how this doorbell is proven to reduce crime in neighborhoods, spreading the word to [homeowner associations], meeting groups, on Nextdoor, and at public safety meetings,” one email from the company read.

The LAPD’s code of ethics prohibits officers from accepting “any gifts, gratuities or favors of any kind which might reasonably be interpreted as an attempt to influence their actions with respect to City business” or using “their position to secure directly or indirectly unwarranted privileges or exemptions for themselves or others.”

The LAPD said using discount codes is “generally not in conflict with our Code of Ethics.” Aguilar also said recommending ways for community members to protect themselves is among the responsibilities of senior lead officers or officers in community relations positions — titles held by some of the officers named in this story who accepted free or discounted devices.

The LAPD doesn’t bar armed, off-duty officers from drinking alcohol despite repeated problems.

Although it’s common for community members to ask officers for recommendations, Cheng, the UC Irvine professor, argues it’s up to the officer to “exercise restraint, according to the code of ethics.” Officers could recommend security systems broadly, said Cheng, who reviewed some of the emails and pointed out that officers didn’t just answer questions about recommendations, but proactively steered the public toward Ring.

Ring quickly made inroads in the department, communicating with at least 125 officers in 2016.

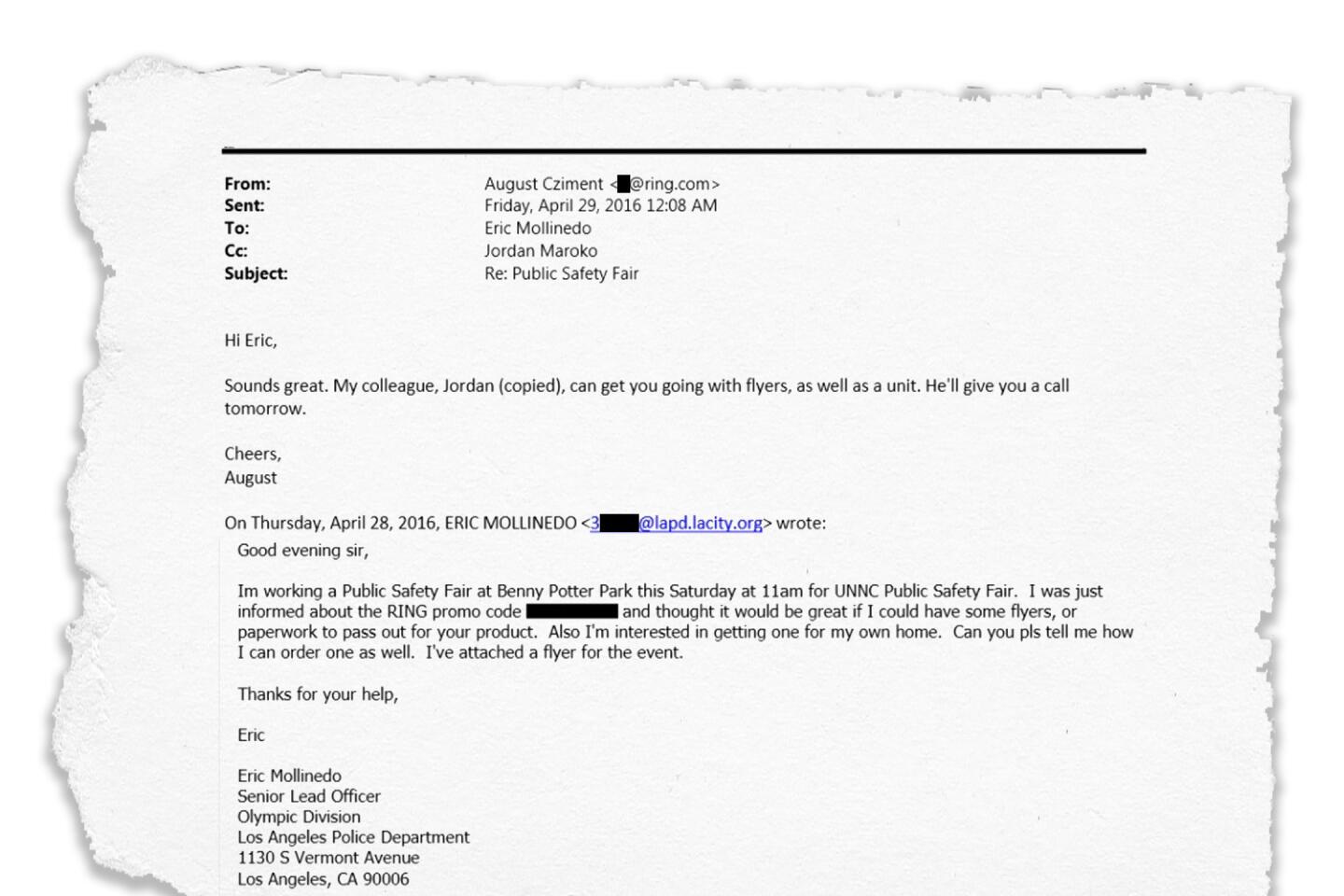

In April of that year, after hearing about arrangements Ring made with other members of the LAPD, Officer Eric Mollinedo from the Olympic division emailed Ring’s director of operations, August Cziment, asking for promo codes as well as information about receiving a unit for his home. Mollinedo said he’d be staffing a booth at a public safety fair. Cziment said Ring would get him “going with flyers, as well as a unit.” Ring also provided Mollinedo a coupon code and encouraged him to distribute it to his colleagues.

After the fair, Mollinedo emailed Ring to let the company know the event was a success. “Was a good day today at the Public Safety fair ... talked up Ring and had (5) officers/reserve officers purchase them!”

In at least 10 cases, officers invited Ring to community events or offered to schedule meetings at their stations primarily for the purpose of allowing company representatives to talk up products and hand out discount codes.

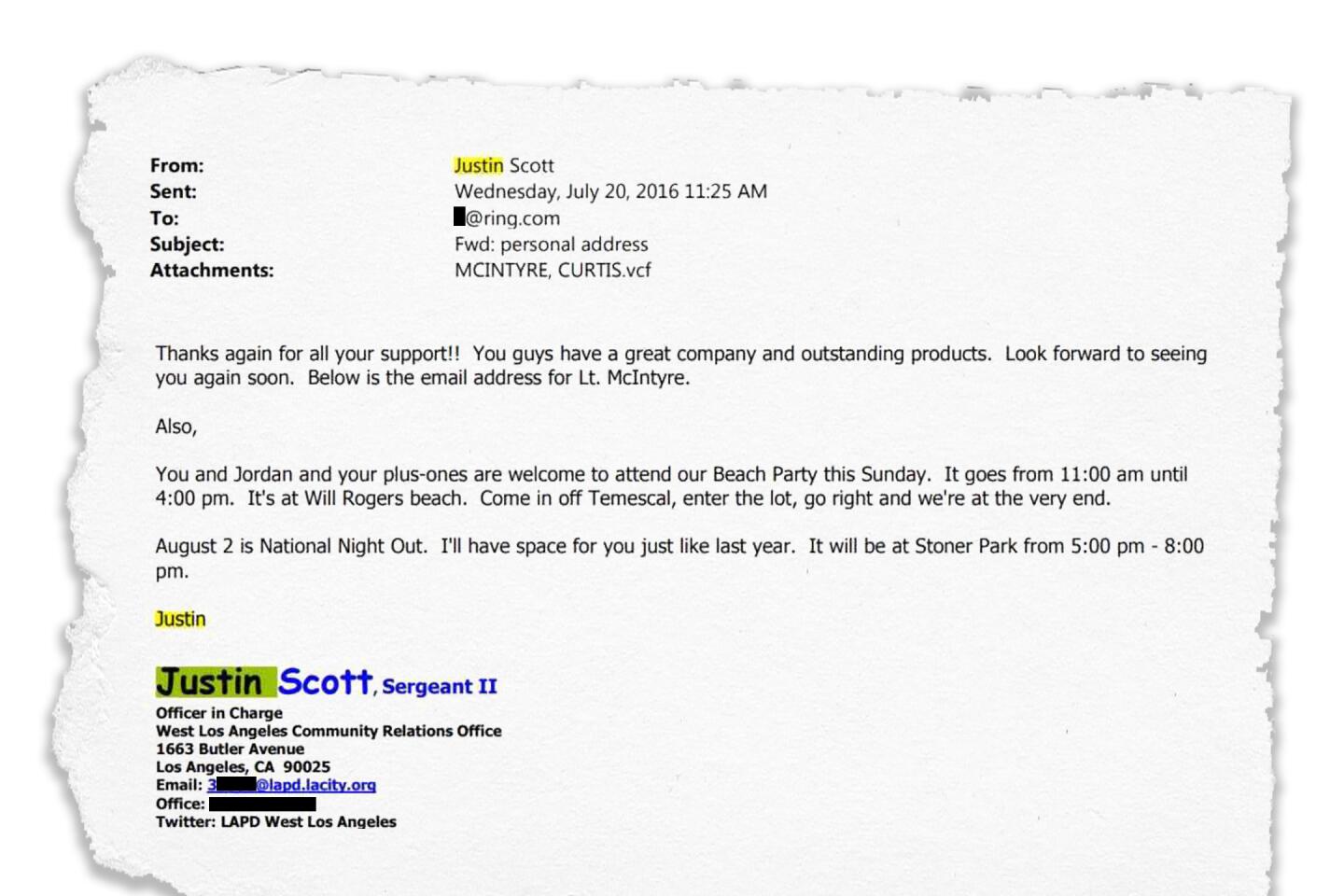

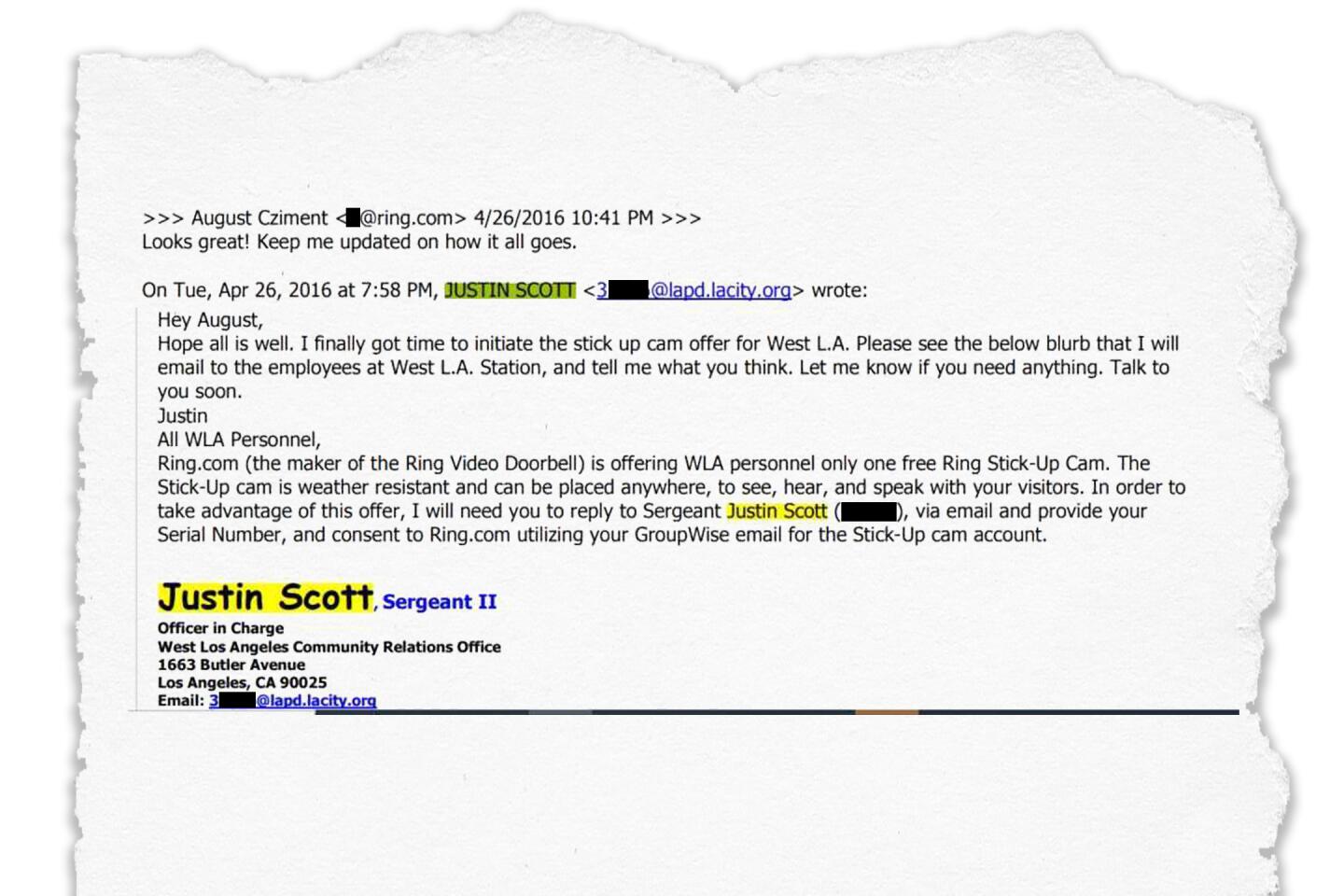

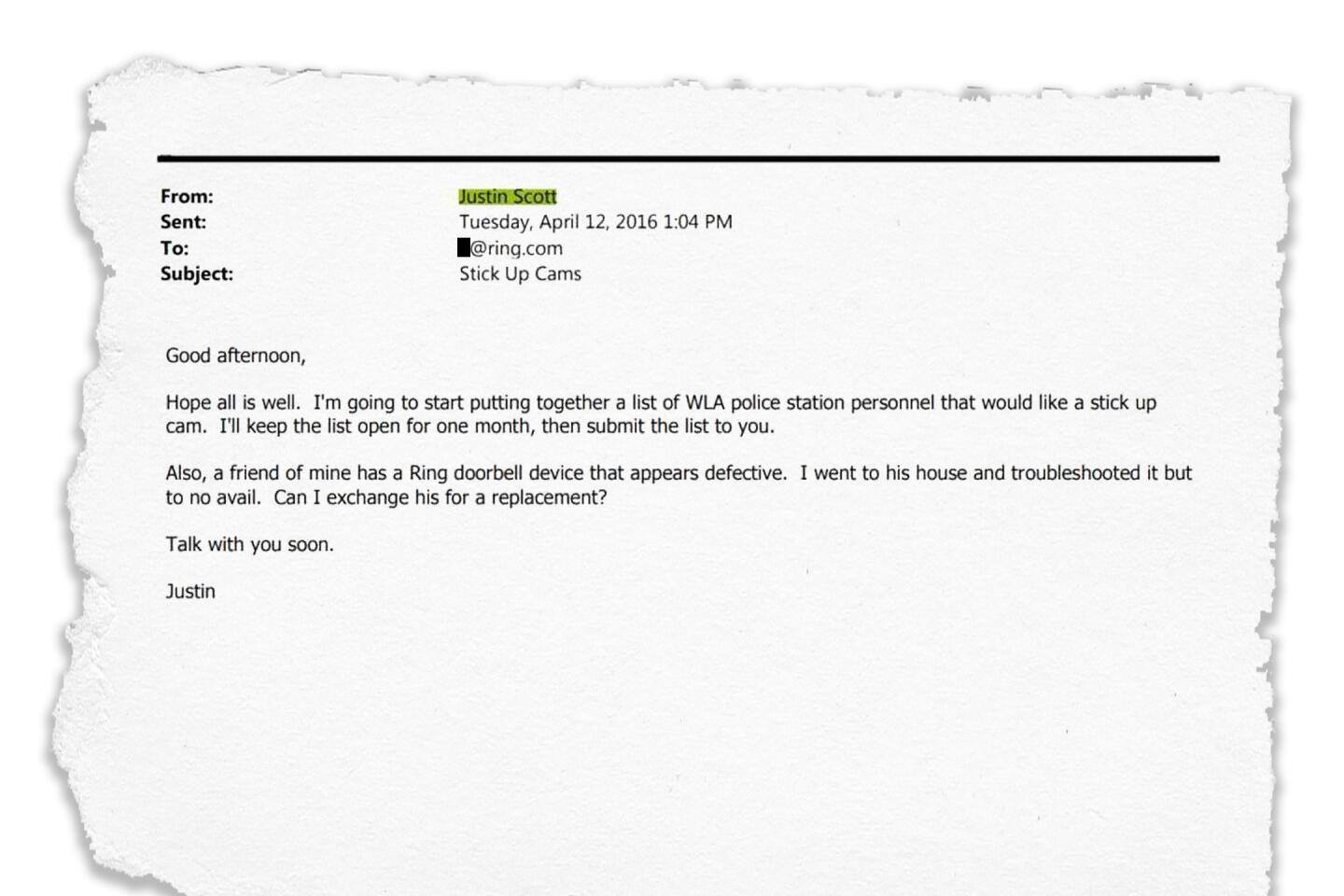

That same month, Sgt. Justin Scott exchanged a series of emails with Cziment about an offer for a free stick-up camera. Ring asked him to share the offer with his entire West L.A. station. Scott agreed, saying he’d keep the option to sign up for the free camera open for a month, and in that same message asked whether he could get a replacement for a friend’s Ring device “that appears defective.”

Later that month, Scott ran promotional language by the company before sending it to fellow officers, emailing Cziment a block of text about the stick-up camera offer for his approval. Cziment replied, “Looks great! Keep me updated on how it all goes.”

Of the 60 officers who responded to Scott’s email asking for a free stick-up camera, four asked whether they could also receive the Ring doorbell that the company gave out for free months prior because they had missed the opportunity at that time. At least three others asked for free stick-up cameras for other officers who didn’t sign up in time. One asked for discounts for family members.

At the time, the device retailed for $199, amounting to a conservative estimate of at least $12,000 in free hardware doled out at just one station.

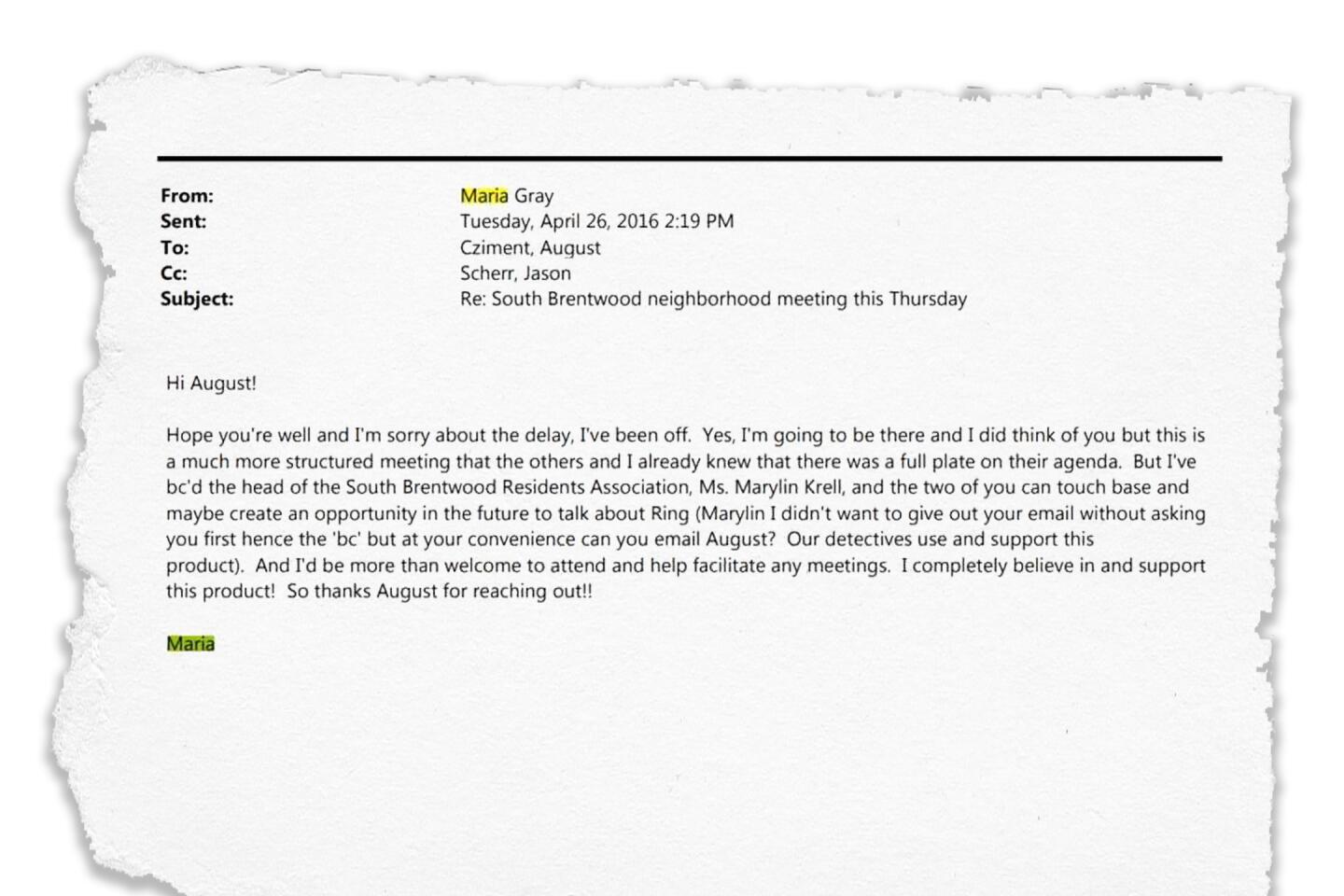

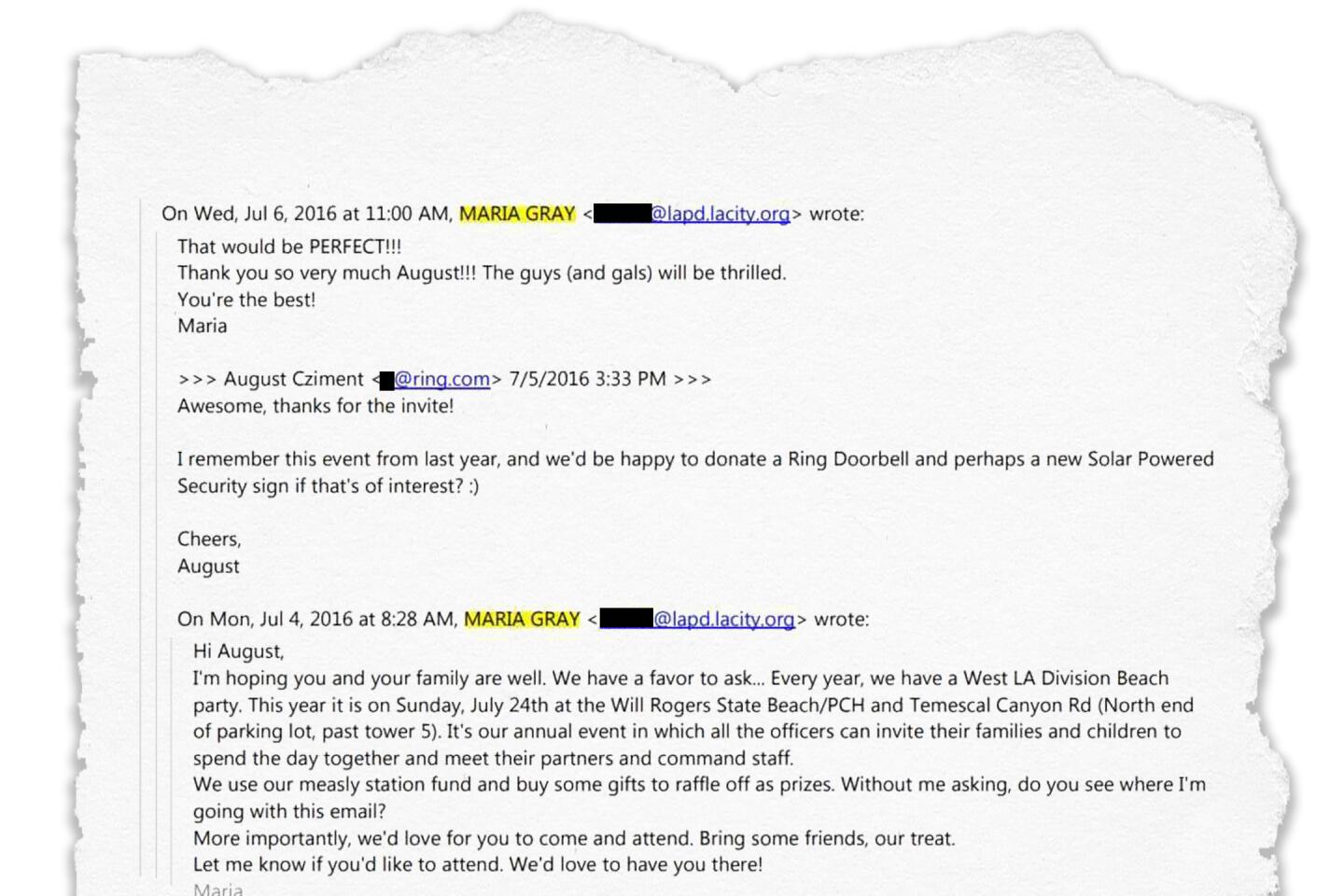

Requests for freebies kept coming. In one case, Officer Maria Gray, who was among the West L.A. police to receive a free stick-up camera, emailed Cziment to invite him to a station family picnic.

“We have a favor to ask.... Every year, we have a West LA Division Beach party.... We use our measly station fund and buy some gifts to raffle off as prizes. Without me asking, do you see where I’m going with this email? More importantly, we’d love for you to come and attend. Bring some friends, our treat.”

Cziment wrote: “We’d be happy to donate a Ring Doorbell and perhaps a new Solar Powered Security sign if that’s of interest? :)”

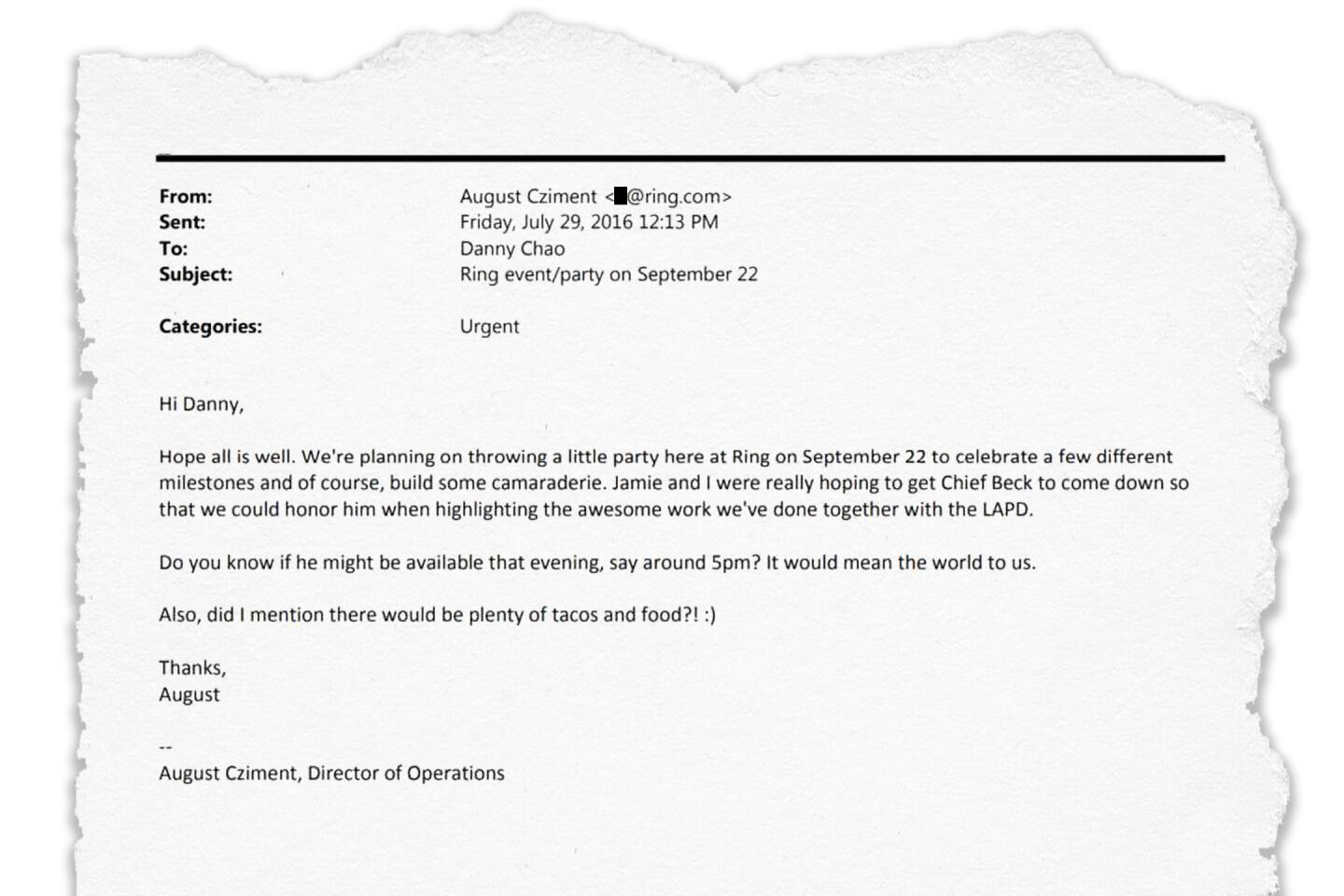

Police invitations also extended to the top of the company: Siminoff, Ring’s chief executive, attended a 2016 police academy graduation as a guest of then-LAPD Chief Charlie Beck.

Marketing to the community

Ring also encouraged officers to promote its products to residents of the communities they policed. The goal was to “spread the word about how this doorbell is proven to reduce crime in neighborhoods,” read one email from Ring offering a free device for an officer to try in his home.

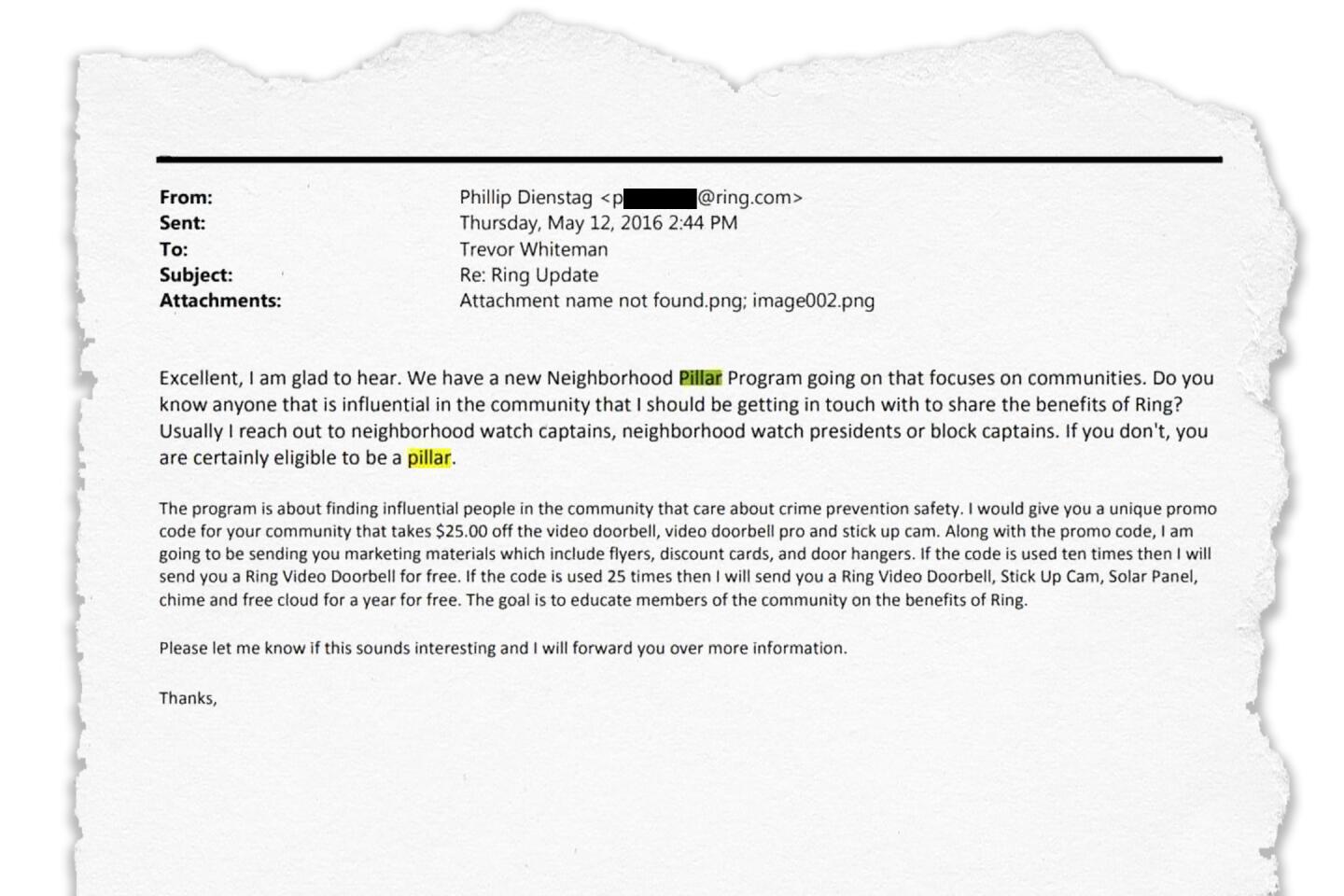

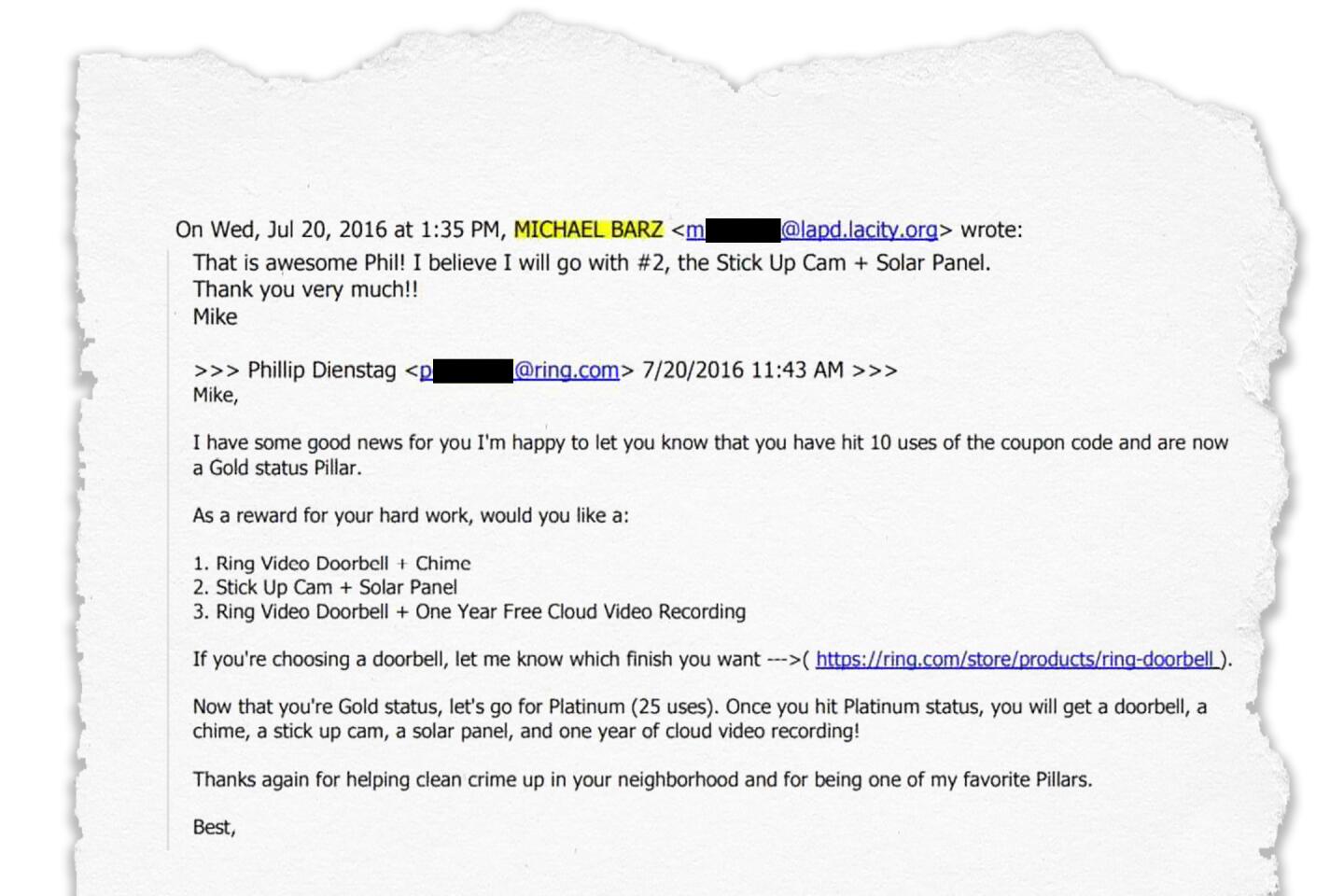

Ring asked officers to help with its “Neighborhood Pillar” program, enlisting its LAPD contacts to “educate members of the community on the benefits of Ring” by handing out promo codes and fliers to so-called pillars — “influential people in the community that care about crime prevention safety.” For every 10 uses of the code, the pillar would get a free Ring device.

Community members Ring considered “influential” included neighborhood watch captains or presidents, one email showed. If the officers didn’t know anyone who fit the bill, Ring invited the officers to take on the role of the pillar.

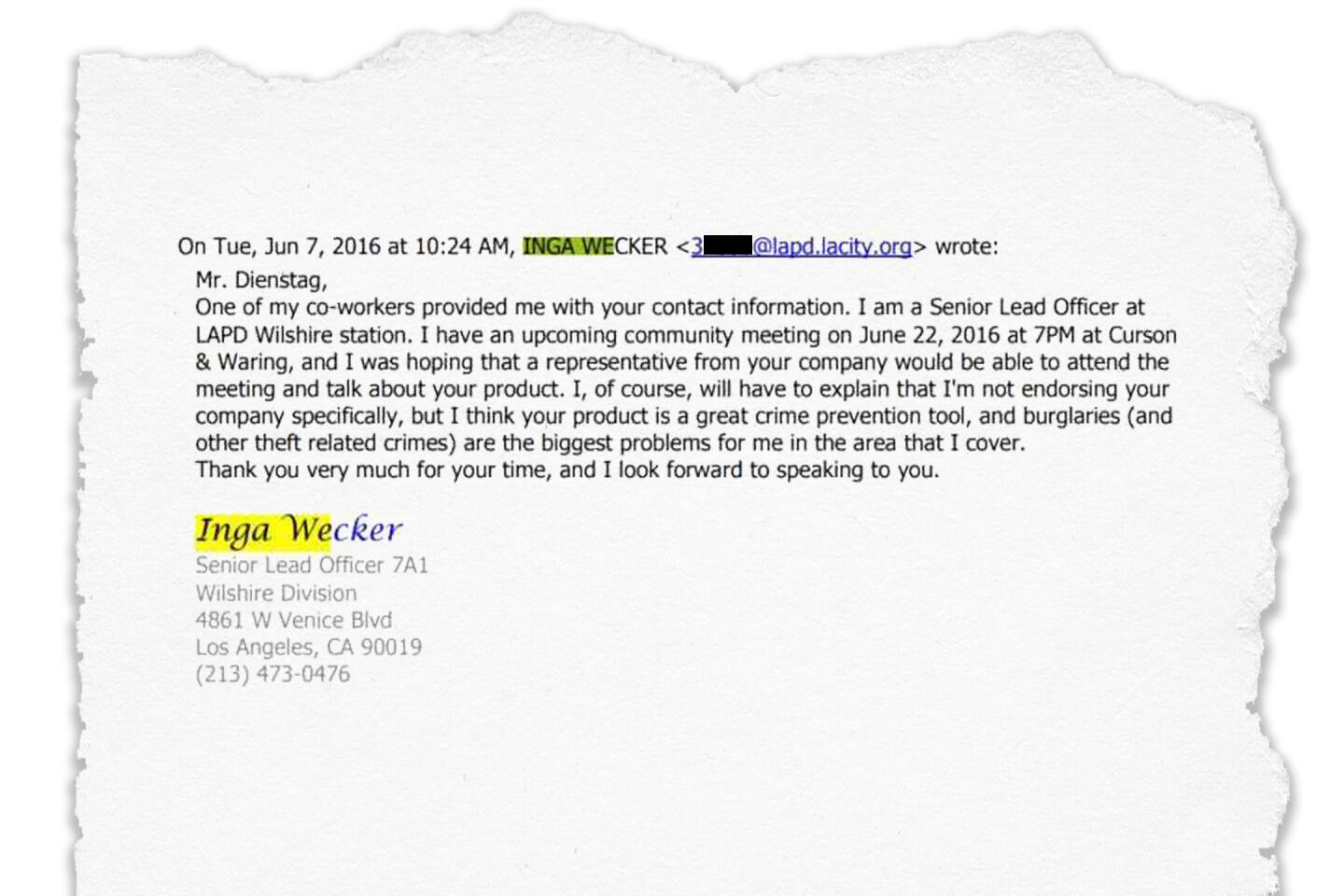

Only occasionally did officers express caution about actively endorsing a product.

In an April 2016 email, Officer Evening Wight said a sergeant in her station had given her permission to share a Ring promo code, but “she cautioned me to word the email so that it won’t appear that we are endorsing the product, merely offering it as an option among others for home security.”

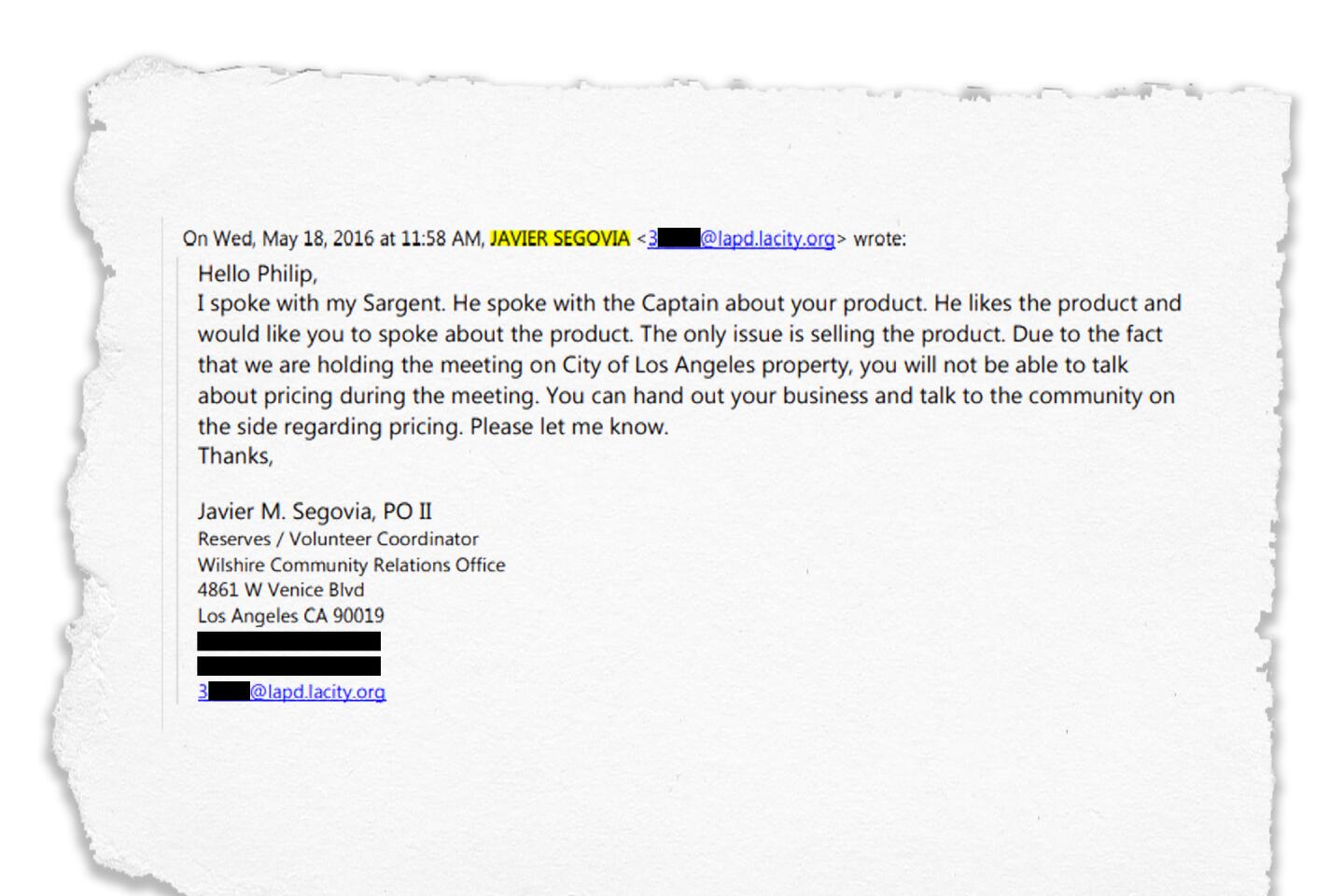

In a May 2016 email, Officer Javier Segovia said his sergeant and captain wanted Ring representative Phillip Dienstag to talk about Ring at a community meeting. But Segovia — who according to the emails had days prior received and installed a free Ring doorbell — advised that because the meeting was going to be held on city property, the company would not be able to discuss “pricing during the meeting.” Instead, he wrote in the email, Dienstag would be able to “talk to the community on the side regarding pricing.”

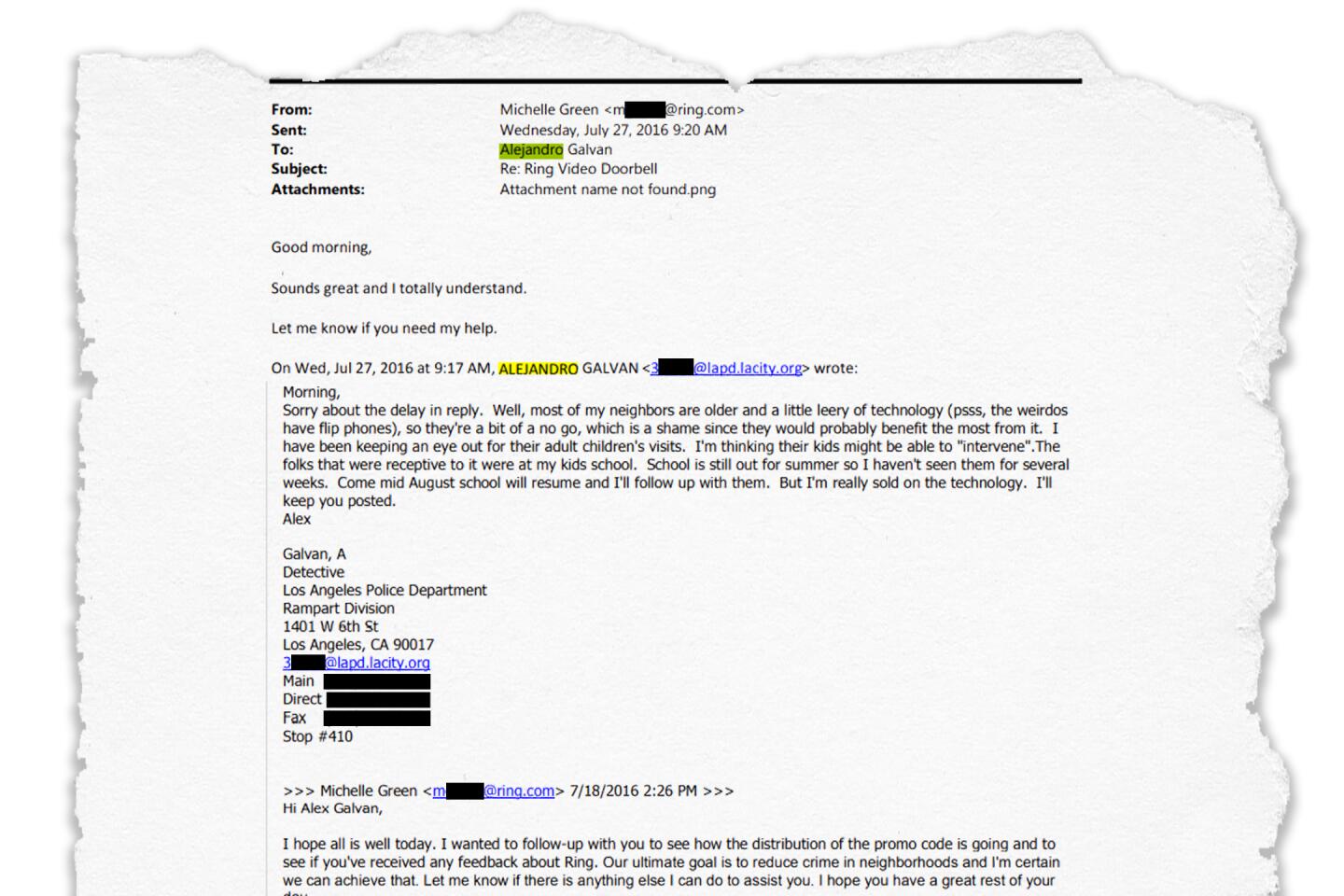

Others went further in endorsing Ring to community members. Officer Alejandro Galvan said he was keeping an eye on his older neighbors, who were “leery” of technology, to see when their adult children would visit so he could talk them into persuading their parents to use a Ring device.

“(Psss, the weirdos have flip phones),” Galvan wrote. “I’m thinking their kids might be able to ‘intervene.’”

In an email connecting Cziment with the head of the South Brentwood Residents Assn. at Ring’s request, Gray — the officer who had invited Ring to the station family picnic — asked whether the neighborhood group could find a way to work with the company. “Our detectives use and support this product,” she said. “And I’d be more than welcome to attend and help facilitate any meetings. I completely believe in and support this product!”

Focus on the app

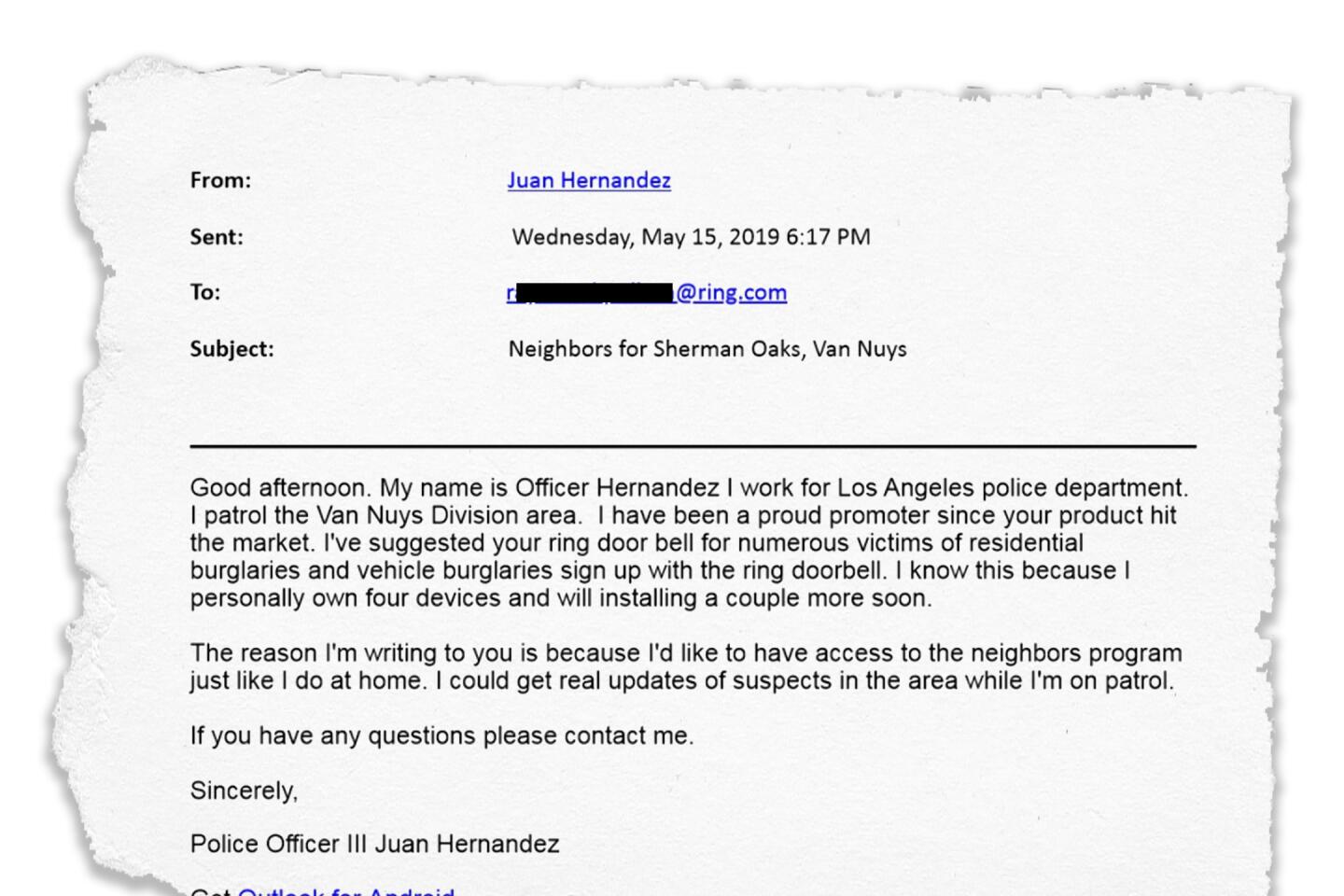

By 2019, the brand ambassador model had evolved. Ring no longer encouraged officers to promote its products with the promise of free or discounted merchandise. Instead, there was a new incentive for officers: growing the network of surveillance devices that they could access more easily than typical security cameras.

Ring at the time was trying to grow its app, called Neighbors. For consumers, the service works much like the community message board NextDoor but with an even greater focus on crime. Residents can share and comment on suspicious or suspected activity in their communities and also post footage from their own cameras.

For law enforcement organizations, the app is an investigative tool. The app is given to law enforcement and public safety agencies free of charge, according to Ring’s website. Officers get crime alerts sent to their inbox, and they can batch download or send mass requests to users for footage directly through the app. It featured an interactive map of all Ring devices in the area; Ring says it discontinued that service in 2019. In response to specific police data requests, consumers can consent to sharing their footage with investigators.

The LAPD began using Neighbors in May 2019, emails reviewed by The Times show.

Aguilar said the LAPD and Ring do not have a formal contract. Terms for similar partnerships in other parts of the country show that as part of the agreement to use the law enforcement portal, officers have been required to “encourage adoption of the platform/app,” in their communities, Motherboard reported.

Emails to LAPD officers show Ring leaned on the brand ambassador model to grow its app. After installing the law enforcement portal, Ring instructed officers to ask community members to join the platform because it “grows in value with each resident that downloads the app.”

Law enforcement stood to benefit from promoting the service.

Obtaining surveillance footage can be a cumbersome process. It can require knocking on doors and asking for permission from the owners of individual cameras, or at times seeking a warrant — which brings a level of transparency and judicial oversight. Using Ring’s vast network, officers could instead request and obtain footage with a few clicks. Emails to Ring show LAPD officers requested access to the company’s investigative tool as soon as it was available to them, praised it and quickly put it to use.

“No more going door to door to look for cameras and asking for footage,” Ring’s instructional video shared with police departments states.

In June 2020, some Ring users received an email notifying them that LAPD Det. Gerry Chamberlain was seeking video recordings from the Black Lives Matter protests, emails disclosed via a public records request filed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation show. During the protests, the notification read, individuals were injured and property was damaged and police were trying to find out who was responsible.

LAPD detectives investigating crimes that occurred during last summer’s George Floyd protests sought out video footage from private residents who own Amazon Ring cameras, according to partially redacted police emails obtained through a public records request.

It was not immediately clear how many users received that notification, where exactly the LAPD was seeking video recordings, and how much material the agency ultimately obtained. By requesting video recordings directly from users, the LAPD avoided the multi-step process of securing a warrant or a subpoena to obtain footage from the vast network of personally owned cameras.

The LAPD said it keeps no record of when and how often officers make requests of Ring users.

After The Times reached out to Ring for comment on this story, the company announced that it changed its policies and now requires police to make requests for video from users in a public forum. “This way, anyone interested in knowing more about how their police agency is using Request for Assistance posts can simply visit the agency’s profile and see the post history,” the blog post read.

In response to The Times’ public records request, the LAPD said that it would be “unduly burdensome” to try to determine how often its officers requested or received video from Ring cameras.

Consumers have embraced doorbell cameras as a useful tool for both home security and convenience. But Heidi Boghosian, a lawyer and former executive director of the National Lawyers Guild, warns of the dangers posed by this private surveillance apparatus, including a potential chilling effect on constitutionally protected freedoms.

“It has so much room for civil liberties violations,” she said.

Experts and activists have for years expressed concerns about the disproportionate effects of surveillance technology on people of color, and further reductions in transparency, she said, could lead to dragnet-style approaches and mass privacy violations.

“When you have the escalation of people’s fears of property or violent crime, it changes the way they interpret ordinary actions of someone walking down the street or ringing their doorbell,” she said, “And that can [lead to] communities of color [being] falsely accused of crimes.”

The lack of transparency is further cause for concern, Electronic Frontier Foundation policy analyst Matthew Guariglia said, because Ring and police departments could be using fear to sell more devices and expand their surveillance powers. In a letter sent to the California attorney general last week, the Electronic Frontier Foundation asked the state Department of Justice to investigate Ring’s relationship with the 145 police departments across California with which it has partnered.

“These partnerships and these relationships blur the boundaries so that people no longer know if they have a real reason to be afraid in their neighborhood or if the police who come to their door and recommend they adopt the Ring or subsidize the cost of Ring just benefit from that relationship,” Guariglia said.

Times staff writer Kevin Rector contributed to this report.

More to Read

Updates

11:45 a.m. June 17, 2021: This story was updated to note that Ring said it stopped providing law enforcement clients with an interactive map of Ring devices in 2019.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.