Scooter start-up promised to serve a whole city. Then it cut out two poor areas

Like 11 other dockless e-scooter companies, Scoot Networks was eager to obtain a coveted permit to do business in San Francisco. In its application, the start-up promised it would “serve more of San Francisco than other operators who will focus on the busiest and most lucrative neighborhoods.”

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, which judged companies in part on their “approach to providing service to low-income residents,” deemed Scoot worthy of one of the two slots in its pilot program, calling it “a safe, equitable and accountable scooter share service.”

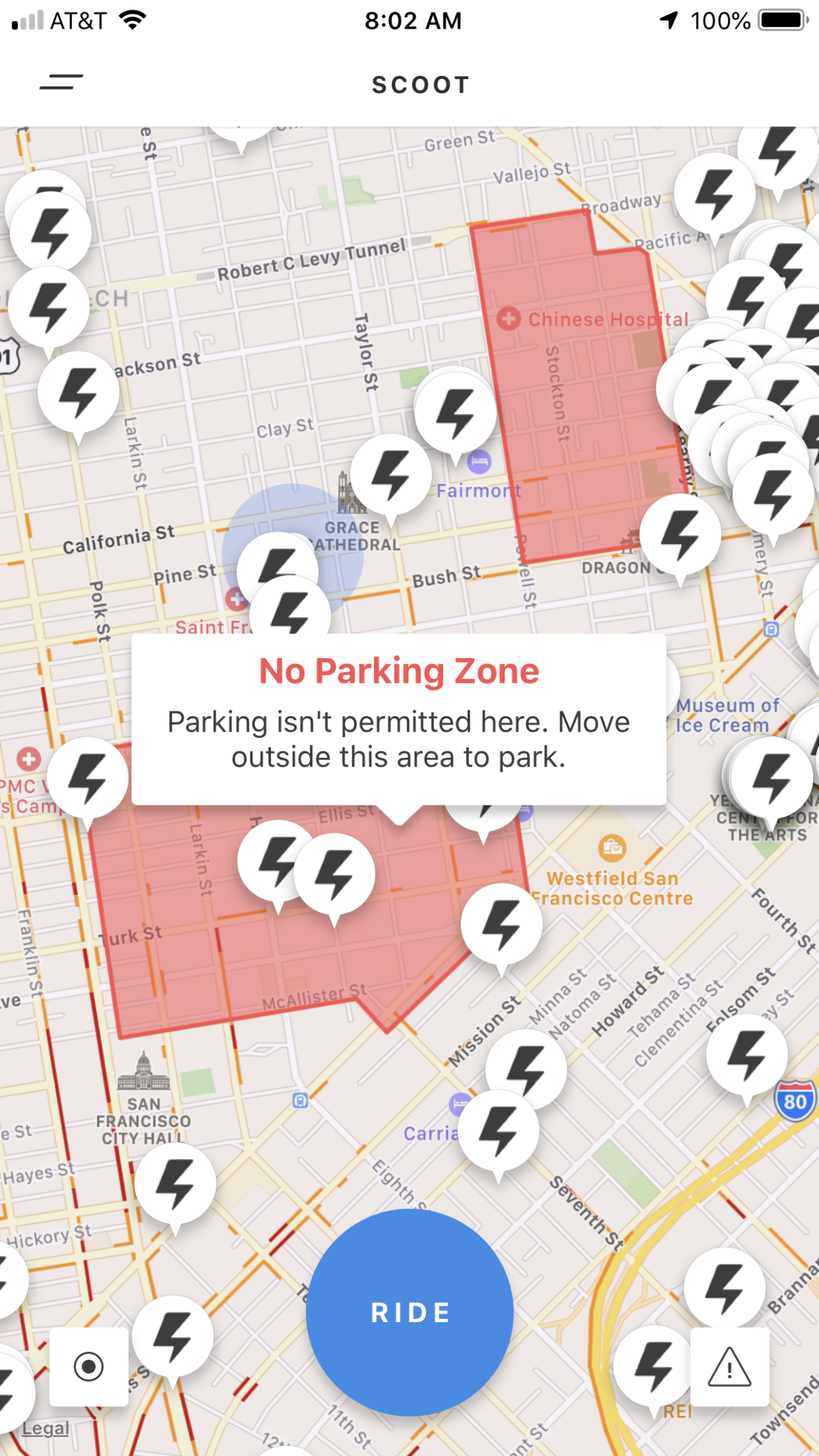

But that doesn’t mean San Franciscans can rent Scoot rides in all parts of San Francisco. The company has drawn a red line around the centrally located but poverty-ravished Tenderloin and in parts of nearby Chinatown, preventing customers from dropping off scooters there.

The start-up, acquired in June by Santa Monica-based Bird, says its no-parking zones are “in compliance with the kick scooter pilot program” overseen by SFMTA.

But the Tenderloin, which is home to a large homeless population, and Chinatown are two of the seven “communities of concern” that Scoot pledged to prioritize serving as a condition of joining the pilot program.

In an October 2018 document, SFMTA laid out the criteria to qualify as one of these focus communities. They included: “Concentration of households with low-income, concentration of residents who identify with a race other than white, private vehicle ownership, concentration of affordable and public housing developments, and Muni routes heavily used by persons of color and low-income transit riders.” The other communities include Western Addition, the Mission, Bayview, Outer Mission/Excelsior and Visitacion Valley.

In evaluating applications for the pilot program, SFMTA specifically scored the companies on whether they included an “approach to providing service to low-income residents, including diverse payment options and fare discounts,” and whether they would serve areas “beyond the downtown core” and be committed to ensuring “availability of scooters in underserved areas.” Scoot and Skip beat out a bevy of better-funded rivals, including Bird and Lime, with the agency praising them for track records that “demonstrated not only a commitment to meet the terms of the permit, but a high level of capability to operating a safe, equitable and accountable scooter share service.”

But as of April, both Skip and Scoot customers were found to be predominantly white men who have a household income of $100,000 or more, according to an SFMTA survey. Additionally, Scoot had only 68 customers enroll in its low-income program while Skip had just 78. The survey, meant to evaluate the scooter pilot program to determine whether to increase the number of scooters each company can operate, concluded that both companies needed to increase outreach in underrepresented communities. Both companies were required to add 150 riders to their low-income programs in order to receive permits for additional scooters.

Mobility companies have long pitched themselves as a means to democratize access to affordable transportation options. Scooter companies in particular have made the argument to city regulators and the media that the affordable, low-friction option of hopping onto a scooter would enable riders in underserved communities and so-called transit deserts to gain access to city centers or public transportation. Scoot’s stated mission is “Transportation for everyone.” The companies have raised this prospect to push back against fleet-size caps, saying that lower caps would make it difficult to serve disadvantaged areas. In their applications, Skip said it would allot 20% of its fleet to communities of concern, while Scoot said its reach would extend “much further” into the Tenderloin and Bayview if it received all the permits it wanted.

“With our requested 1,250 powered scooter permits, and eventually 2,500 or more, Scoot will serve more of San Francisco than other operators who will focus on the busiest and most lucrative neighborhoods,” Scoot wrote in its application. “A smaller fleet would be spread too thinly to sustainably serve both the busy northeast and important but less busy neighborhoods south and west.”

Some city regulators have been responsive to such appeals. In Los Angeles, as part of a yearlong permit, the city’s Department of Transportation allowed companies to deploy an additional 2,500 scooters in disadvantaged communities, on top of the 3,000 scooters permitted for the whole city.

Asked about the no-parking zones, a Scoot spokesperson told The Times in a statement: “Scoot works closely with the SFMTA to ensure we are meeting the needs of the community. We are in compliance with the current kick scooter pilot program and are exceeding in areas such as Community Plan members.”

SFMTA media relations officer Ben Barnett said the agency is aware of the situation and is looking for a solution with the company, but added that the agency did not currently dictate how companies serve these designated communities of concern.

“They are required to maintain 20% of their scooters in [the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s] Communities of Concern at all times — a target which they have consistently met,” Barnett said. “The rest of our Pilot permit was not prescriptive about service area and it is up to our two permittees to decide which parts of the City to serve, so while we can encourage them to serve certain neighborhoods, it’s ultimately up to them.”

Between December and March, more than 60,000 scooter rides started or ended in communities of concern, according to the SFMTA. That represents 52% of all trips made in those months.

As part of the yearlong pilot program, Scoot is authorized to operate only 625 scooters and Skip operates 800 scooters. The SFMTA is now accepting applications from other scooter companies seeking to launch in San Francisco, potentially upping the number of scooters each company is allowed to operate from anywhere between 1,000 and 2,500. The agency did not respond to questions about whether this would reflect poorly upon Scoot’s ability to get a permit in the future.

Bird, Scoot’s parent company, also has no-parking zones in parts of Los Angeles. This was in part a response to cities’ bans on the scooters as well as community complaints. In San Francisco, where Bird does not operate under its own brand, its app shows Scoot’s service areas.

Despite its ambitious request for permits, Scoot did not initially end up using them all. In April, in an evaluation of the pilot program, SFMTA criticized Scoot for falling short of its rhetoric. “Scoot deployed a fleet size much smaller than the permitted 625 during the first four months of the Pilot, with commensurate low ridership numbers,” the agency wrote. “Scoot must work to deploy an adequate fleet to service their entire service area, including Communities of Concern. Finally, both permittees should work to ensure that scooters are available and utilized beyond the downtown core.”

More to Read

Updates

6:10 p.m. Aug. 16, 2019: Following publication of this story, Scoot publicly responded to The Times’ report, saying community leaders in the Tenderloin and Chinatown asked for the no-parking zones, and made a minor change to the way the no-parking zones display on its map. Coverage of that response is here.