The Download: Why emojis are a no-brainer for digital communication

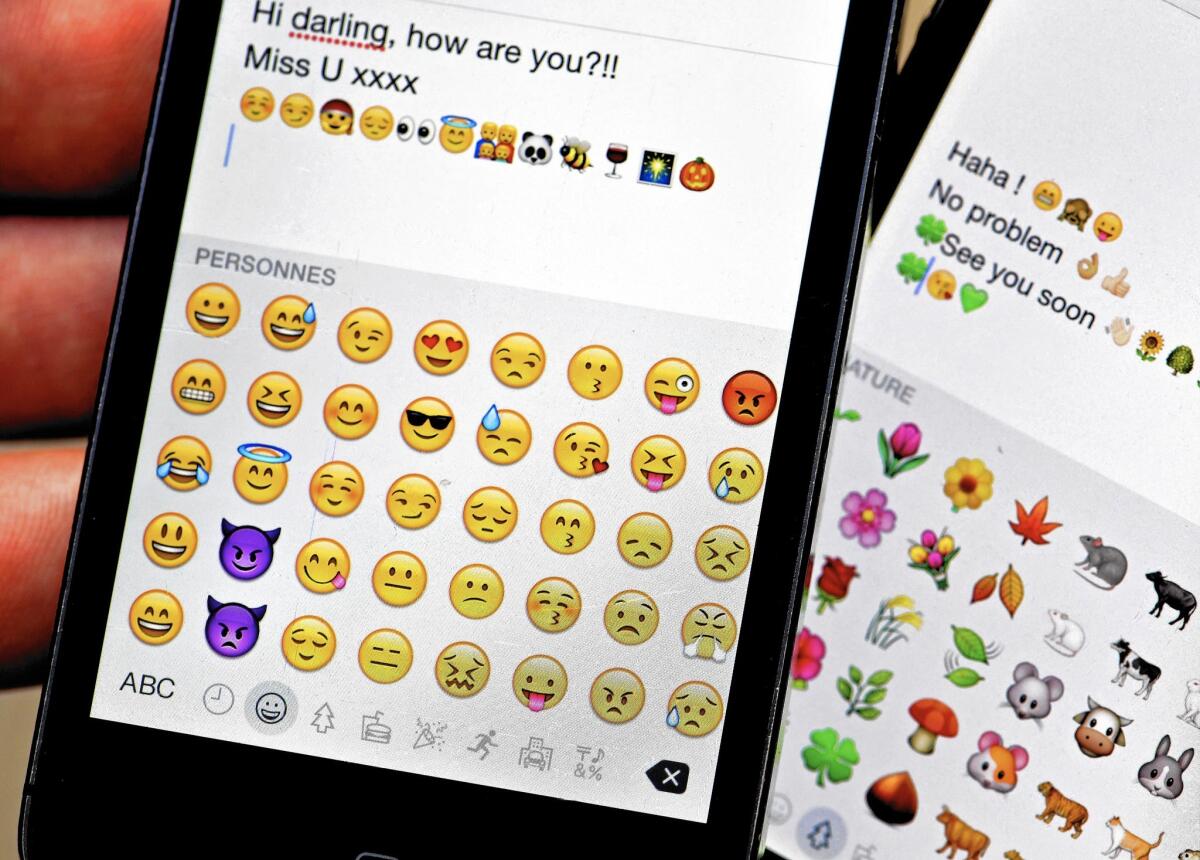

reporting from san francisco — When the Oxford English Dictionary declared an emoji its 2015 word of the year, it was a bit of a head-scratcher.

The emoji it singled out — an image of a laughing yellow face crying tears of joy — did not fit most people’s definition of a word. To some, it was even less of a word than shortlisted nominee “lumbersexual” (a young urban man who cultivates an appearance and style of dress suggestive of a rugged outdoor lifestyle).

But for linguists around the world, the announcement wasn’t about whether the Oxford English Dictionary had lost it. (It hadn’t — most linguists agree a word is a discrete unit that is meaningful; emoji fit that definition.) Rather, it was a recognition of the enormous effect yellow smiley faces and other colorful emojis representing food, animals and hand gestures have had on the way people talk online.

Don’t believe them? A 2015 study by Bangor University linguistics professor Vyv Evans found that 80% of smartphone users in Britain use emojis. When the research focused on people under 25, almost 100% of smartphone users text with emojis. According to a SwiftKey report, 74% of Americans use emojis every day.

Aside from widespread adoption of the icons, which began after Apple made emojis available on its iOS mobile operating system in 2011, with Android following in 2013, emojis have been one of the biggest communication breakthroughs since people took to the Internet.

Look at it this way, Evans said: There are estimates that as much as 70% of the meaning we derive from a face-to-face encounter with someone comes from non-verbal cues: facial expressions, intonation, body language, pitch. Which means words account for only around 30% of what we communicate.

As an example, he noted the huge difference in meaning between saying “I love you” as a statement with a falling intonation as opposed to “I love you?”

Move this online, where emails, text messages and instant messages mostly allow us to communicate with words, and you can see how messages can lose their meaning or be misinterpreted. Evans even has a term for it: the Angry Jerk Phenomenon.

“You’ll recognize it instantly,” he said. “You get an email from someone who you know to be calm and sane, and they come across as a completely angry jerk. When you press the send button on a message, the instant it is sent, you lose control over how it’s interpreted.”

A December report from Bloomberg found that 8 trillion text messages are sent each year. That’s a lot of opportunities for a message to be misinterpreted.

Cue the emoji.

Emojis originated in Japan in the late 1990s, when wireless carriers created sets of digital stickers people could use in text messages.

Elsewhere, people had long used emoticons — visual expressions strung together using symbols such as parentheses, dashes and colons, like :) to denote a smiley face. Where text took the empathy out of messages, emojis and emoticons put it back in.

But emojis quickly surpassed emoticon use for two key reasons: There’s a lot more that people can communicate with emojis. (“I can make an emoji that’s a whale or a penguin,” said Internet language expert Gretchen McCulloch. “I don’t even know how I would do that with emoticons.”)

SIGN UP for the free California Inc. business newsletter >>

And once emojis were incorporated into Unicode — an international system that standardizes characters across different operating systems so when you type “:-)” into your iPhone or Android phone, the symbols automatically turn into a yellow smiley face — they became accessible and easy to use.

Add to that the belief that “humans as a collective species are programmed to use visual communication” (that’s from linguist Neil Cohn, whose own research focuses on how people have a biological inclination to draw things), and emojis became a no-brainer for digital communication.

Language experts note that the real innovation behind emojis lies in their ability to help people online say what they mean, so when they write “What the heck?” they can signify with an accompanying laughing emoji or an angry-faced emoji whether their statement is an expression of amusement or outrage.

And try as people might, emojis aren’t here to replace language. Many streams of emojis easily can get lost in translation.

For instance, a group of 800 people pooled their efforts to translate Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” into emojis. The translated epic is titled “Emoji Dick.” Its famous opening line, “Call me Ishmael,” is communicated through five emojis: a telephone, a man’s head, a sailboat, a whale and a hand gesturing “OK!”

Which might make sense, but only if you know what you’re looking for, McCulloch said.

“For example, Domino’s Pizza tweeted a pizza emoji, then some space, then a person emoji, a cloud emoji and a burger emoji,” she said. “And somebody retweeted that with the caption: ‘I fart burgers as I run to my one true love, pizza.’ Clearly that’s not what Domino’s meant by it, but that is what it could mean.”

Things that are quickly adopted have a tendency to quickly go away. But the way emojis fit so seamlessly into the way we communicate and their ongoing ubiquity gives linguists the belief that they aren’t going anywhere any time soon.

The Unicode Consortium, which is made up of the major software developing stakeholders such as Apple, Facebook, Google and IBM, continues to process applications for new emojis. Anyone can submit a request for free by heading to the Unicode website and writing a detailed proposal for the emoji. The process in which the Unicode technical committee decides if an emoji will see the light of day can take up to two years. The consortium receives around 100 proposals a year, and approval rates vary year to year.

There are currently 74 new emojis shortlisted for 2016, including a dancing man, a croissant and pancakes.

Anyone can also create his or her own sticker sets and upload them to the Google Play or iTunes App Store, bypassing the Unicode process, as the Finnish government did when it launched 30 Finland-themed stickers that could be downloaded and used in text conversations.

One of them is a heavy-metal headbanger. Another is a naked man and woman in a sauna. But these stickers are different than emojis. Stickers have to be downloaded, and when people send them, they are sending an image. Emojis are made up of Unicode characters, and are standardized across operating systems.

“Digital communication is here to stay,” Evans said. “We’re all virtually connected, and we’re in the midst of a digital revolution. For it to be as successful as spoken language, it needs this kind of system to complement and support the messages coming from text.”

The system might grow to include an emoji for every facial expression, gesture, food or flag. Or, as Cohn, the linguist, hopes, as the system matures, people will want fewer, but more useful emojis.

“Why isn’t there an emoji of someone with a face that has rolling eyes?” he said. “That would be really useful.”

Twitter: @traceylien

MORE BUSINESS COVERAGE

U.S. cruise lines look for growth in China’s waters

‘Kung Fu Panda 3’ is expected to fortify DreamWorks Animation’s ties to China

Lazarus: When collectors call, demand proof of your debt