By many measures, downtown Los Angeles’ newest apartment tower is over the top with such gilded flourishes as stone tiles from Spain lining the elevator cabs and hand-troweled Italian plaster on interior walls. Hummingbirds have somehow found the fruit-laden trees decorating the outdoor lounge on the 41st floor.

For Stuart Morkun, the developer who oversaw construction of the recently completed Figueroa Eight skyscraper, it was the porte cochere, where residents leave their cars with valets, that really stood out. The travertine used to build it was mined from the same quarry outside of Rome that supplied stone for the Colosseum, New York City’s Lincoln Center and the Getty Museum.

“That’s when I knew we were crazy,” he said.

The decision by Mitsui Fudosan America, the Japanese real estate company that owns Figueroa Eight, to spend as much as $350 million to build an ultra high-end residential tower in downtown L.A. might at first seem to be a risky gamble.

After all, L.A’.s homelessness crisis is on stark display on many downtown streets, and glitzy office towers looming nearby are dealing with low occupancy and falling values as law firms, financial service companies and other businesses that filled them before the pandemic have reduced space or departed altogether.

In fact, the decision to go big on Figueroa Eight, which opened last month, reflects an unusual disconnect playing out in the neighborhood: While downtown as a place to work still struggles to find its footing post-lockdown, downtown as a residential center is thriving. It boasts a large stock of housing in fancy new high-rises and converted historic buildings at rents that are well below those on the popular Westside.

The developers of Figueroa Eight declined to say how many of its 438 units they’ve rented out so far, but said leases are on track with projections and that the tower is attracting strong interest.

Downtown’s urban feel drew attorney Leslie A. Ridings, an L.A. native who enjoyed living in New York while he attended college.

“Downtown Los Angeles is kind of the only game in town, right?” said Ridings, who lives in a high-rise at 8th and Olive streets. “It’s the only ‘city’ in the city. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we’ve got.”

Downtown has about 90,000 residents, a slightly higher population than Santa Monica or Santa Barbara, said Jessica Lall, head of real estate brokerage CBRE’s downtown office. They live in 47,000 residential units, most of which are apartments rented at market rates.

But for a variety of reasons, most of L.A.’s downtown residents don’t work there. It is an unusual reality not seen in many other big cities that decouples the apartment market from the fate of the millions of square feet of offices for rent in the area because residential landlords do not rely on office workers to fill their units.

The pandemic has had a dramatic, far-reaching effect on downtown that exposed the dual realities of its real estate. Office buildings emptied first by government decree and later by choice as remote work grew acceptable to corporate America. Apartment occupancy downtown took a dip early in the pandemic and then bounced back as tenants decided it was an acceptable place to live even if they worked elsewhere.

The successes and struggles of Brookfield, a Canadian real estate company that owns residential and office properties downtown, illustrate this stark divide. Little more than 15% of the tenants in downtown apartments owned by Brookfield worked in nearby office buildings before the COVID-19 pandemic, managing director Mike Greene said, and the percentage today is about the same. Occupancy in Brookfield’s nearly 2,400 downtown units fell to nearly 80% early in the pandemic, he said, but soon rebounded to about 95%, where it remains.

Office landlords only dream of such occupancy figures. CBRE reported that just 65% of downtown office space was spoken for in the first quarter of this year. Brookfield, meanwhile, which also owns offices through a separate entity, is among downtown landlords that have defaulted on office building loans in recent months and lost their properties to their lenders.

Property owners and retail businesses such as shops and restaurants have lamented the loss of office workers on the streets, as well as the swelling number of homeless people since the pandemic began. The disappearance of workers and the businesses they supported threatened to undo decades of work by developers and city officials to build downtown’s financial district into a residential destination.

Business leaders in the early 2000s were painfully aware that downtown L.A. lacked the vibrancy of other big cities because it had so few residents, but was stuck in a chicken-and-egg situation: People didn’t want to live there because it lacked restaurants, grocery stores and other typical city-life amenities, but merchants didn’t want to set up shop because few lived there.

The stalemate began to break around 2000 with an ordinance that made it easier to redevelop obsolete office buildings into housing.

The revival of downtown

The relocation of the Lakers, Clippers and Kings pro sports teams to the new downtown arena then known as Staples Center brought thousands of sports and music fans and led a wave of development south of the financial district.

Decades of efforts to add rail service and thousands of apartments and condominiums helped create a more vibrant downtown that was taking on the flavor of other big cities before the pandemic.

The revival of downtown has persisted for several reasons. One is that it boasts a large amount of fairly new housing — a result of downtown being zoned for dense development, which means the path to construction approval can be easier than it is in other parts of the city.

A city-approved development plan calls for downtown to accommodate 20% of the city’s projected housing growth between now and 2040, Lall said. Downtown has already accounted for nearly 30% of all new multifamily units built in Los Angeles since 2004, according to CBRE.

Part of downtown’s appeal is also its price, at least compared with the Westside’s choice rental markets.

“If you compare Santa Monica and Marina del Rey, it’s 38% more expensive to live there than it is to live downtown,” Lall said.

And as downtown apartment landlords hustle to get their buildings, leased they can be generous with move-in incentives, such as periods of free rent and moving allowances for signing a lease.

Figueroa Eight is clad in brushed aluminum, stainless steel and lightly tinted glass. Other deluxe high-rises such as Brookfield’s nearby Beaudry and Atelier apartment towers are also wrapped in metal and glass with tall tinted windows.

“I think Figueroa Eight is a very nice building, of quality, which is also good for our city,” said architect Richard Keating, who is not involved with the building. “Often in places where the weather is benign, you end up building cheaper buildings because you don’t have to defend against the winter in Chicago or New York. So then we get high-rises built with stucco, which I frankly think there should be a law against.”

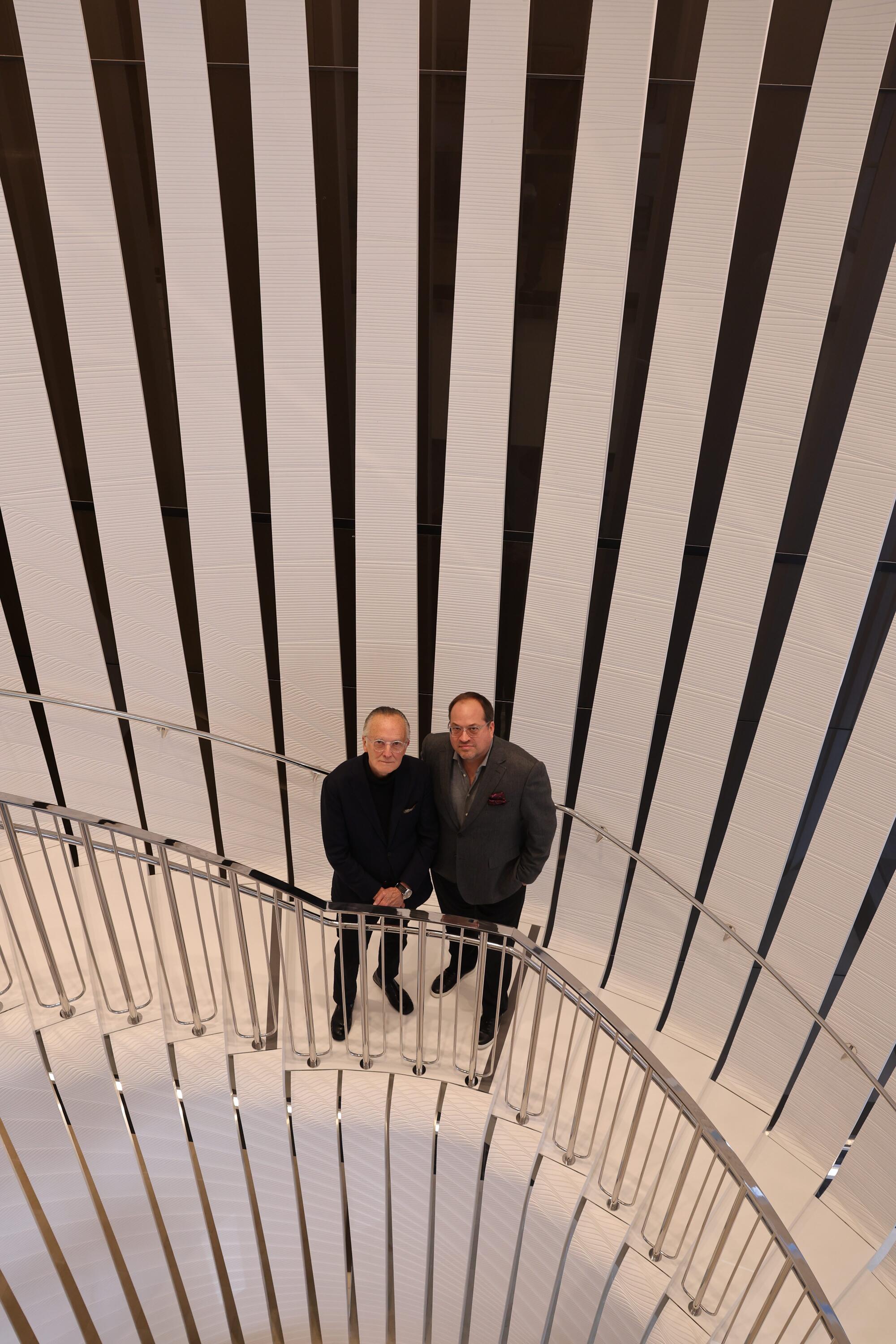

The building’s L.A.-based architect, Scott Johnson of Johnson Fain, has worked in Japan and says there is a different mindset in the country about real estate development.

“So much of American construction is more speculative in nature,” he said, where developers focus on limiting construction costs, filling a building with tenants and then selling it. “The Japanese are fundamentally not like that” and hold property long-term.

Upmarket apartment complexes have dramatically ramped up their amenities such as dog runs, golf simulators and maid service in recent years to attract and retain tenants. And coming out of the pandemic lockdown, Mitsui Fudosan America and other landlords have pivoted to making their buildings friendly to tenants who work from home.

There is dedicated co-working space for people who want to work outside their apartments without leaving the building and other lounging spots such as poolside cabanas and outdoor spaces where tenants can set up a laptop.

“People’s day-to-day surroundings are becoming more important,” Morkun said, now that they’re not spending every workday away from home.

shoot pool in the common area of Figueroa Eight.

Luxury apartment landlords are also going beyond offering tenants alternative spaces to work by trying to give them the chance to drop their memberships in gyms and social clubs such as SoHo House because the building has alternatives for working out and entertaining. That may encourage them to spend more on rent, Morkun said.

Figueroa Eight’s indoor and outdoor “fitness studio” includes free classes and a hot-yoga room. Socializing zones include a poolside lounge with an outdoor bar, fire pits, grilling stations and the 41st-floor Sky Lounge with entertaining areas including a bar and dining room looking out on the skyline. There is also an outdoor hammock garden if you prefer to relax alone.

The Beaudry has a bocce ball court, putting green, golf simulator and poker game room among its tenant lures.

Tenants’ top desires are pretty simple, though, Morkun said. His company’s research showed “what people care about are pets, parking, a fitness center and storage in their units.”

Landlords are bending over backward to accommodate pets. Morkun claims his building has downtown’s largest dog run, which tenants may want to use late at night instead of taking their pooches down to the sidewalk.

“Either you solve the Fido problem or everyone is going to walk away saying, ‘It’s a beautiful building and we’d love to live here, but ....’”

The completion of Figueroa Eight marks the end of a construction boom, landlords said, which could help keep occupancy high in existing buildings.

Over the last decade, an average of more than 2,000 new apartment units have hit the downtown market each year, Brookfield’s Greene said. But with the recent delivery of the Beaudry and Figueroa Eight, “the delivery pipeline sort of falls off a cliff.”

With construction costs and interest rates deemed high by developers, he said, “we don’t expect new projects breaking ground in a meaningful way until something shifts.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.