Column: Nikki Haley is as bad on abortion and health as any other Republican

Nikki Haley blocked the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act while she was governor of South Carolina. Her policies on abortion rights are execrable. Her home state has one of the nation’s worse records in the nation on maternal health — indeed, on health generally.

Since Haley says she’s staying in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, despite coming in second to Donald Trump in the New Hampshire primary, there’s no time like the present to examine her positions on the all-important issue of healthcare.

A thousand political takes have bloomed in newspapers and on the airwaves since Haley expressed her determination to keep running. Too many of them deal with whether she really has a chance to beat Trump and what Trump says or thinks about her or what she thinks of Trump.

It’s easy and lazy to expand Medicaid because all you’re doing is giving people money to buy them time.

— Nikki Haley

It’s much more important to contemplate what a Haley presidency would mean to Americans confronting those thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to, especially among low-income Americans and women of childbearing age. The general answer is that it’s ugly.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

South Carolina ranks 37th in healthcare performance among all states, a ranking by the Commonwealth Fund based on reproductive care and women’s health, access and affordability of healthcare, premature deaths from preventable and treatable causes, and other factors.

Let’s dive in.

We can start with the most important healthcare issue on the partisan landscape: abortion. South Carolina’s rules on abortion are among the most restrictive in the nation. The rules were implemented under a law passed after she left the governorship, but she never specifically disavowed them either.

The state bans most abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, a time when many women don’t know they’re pregnant. Women seeking abortions must be offered antiabortion counseling and wait 24 hours afterward. Minors can’t receive abortions without the approval of a parent or legal guardian.

Abortions must be performed by physicians, which bars the involvement of midwives and other healthcare professionals. Medication abortions — that is, via pills — must be administered by physicians in person, not via telehealth sessions or through the mail.

The state prohibits even private health insurance plans offered through Obamacare to include abortion coverage except in narrow circumstances. Haley signed that law as governor. Its Medicaid program doesn’t cover abortion.

During the GOP candidate debates, Haley has tried to dodge questions about her abortion policies, or at least shroud them in a miasma of verbiage. “We need to stop demonizing this issue,” she said during the Aug. 23 GOP debate in Milwaukee. “Unelected justices didn’t need to decide something this personal, because it’s personal for every woman and man.”

But she implicitly praised the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned the national right to abortion established in the 1973 ruling in Roe vs. Wade.

Dobbs placed abortion legislating in the hands of state lawmakers. “Now, it’s been put in the hands of the people,” Haley said during the debate. “That’s great.”

But that circumvented the reality that even in states where voters have backed abortion rights by wide margins at the ballot box, such as Ohio, legislators have been attempting to reimpose abortion restrictions despite the votes.

Haley has said that as president she would sign a national abortion ban if it reached her desk. She tries to leaven that determination by arguing that Congress would be unlikely to pass one.

It’s proper to note that abortion restrictions and indicators of maternal and infant health more generally tend to go hand in hand. That seems to be the case in South Carolina, which persistently has ranked low among states on maternal and infant health.

The state had the ninth-worst maternal death rate in the country in 2019-21, according to the Commonwealth Fund — 35.3 deaths per 100,000 live births. (California’s rate of 9.6 was the best in the country; the U.S. average was 32.9.) The state’s rate was lower while Haley was governor, running between about 26 and 28 per 100,000 births, but was consistently worse than the U.S. average by eight to nine percentage points throughout her tenure.

Iowa and Nebraska reject U.S. money for a summer children’s food program even though the federal government is picking up the tab.

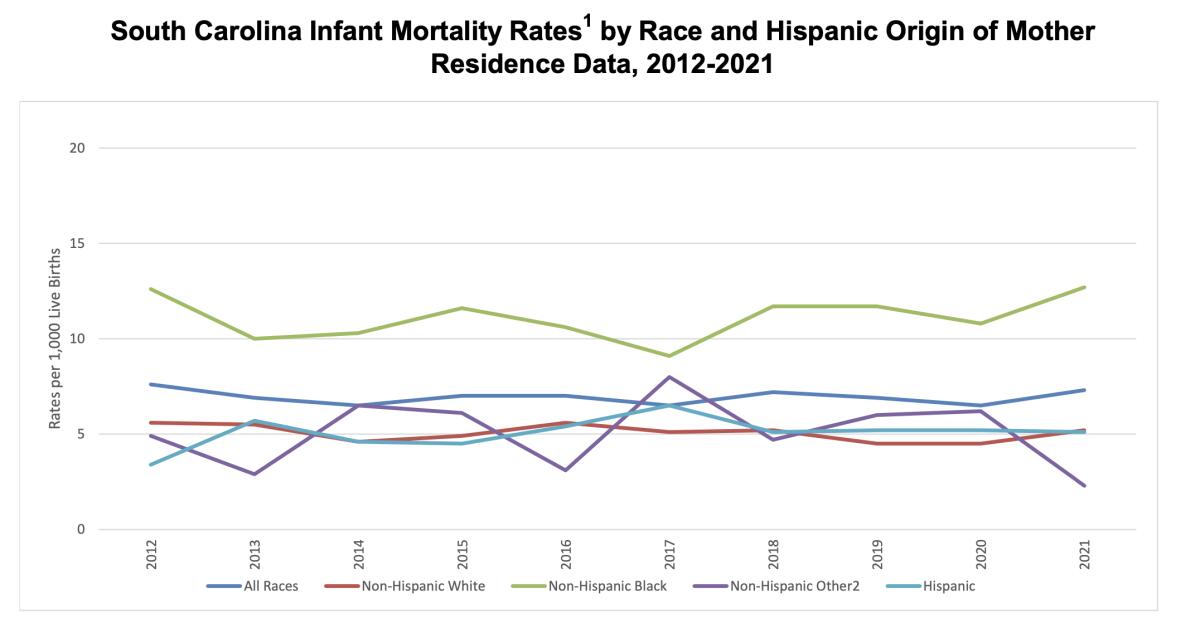

South Carolina also had the fifth-worst infant mortality rate in the country in 2021, at 7.26 deaths per 1,000 live births — better than only Mississippi, Arkansas, Alaska and Alabama — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The rate fluctuated between 6.4 and 7.5 while she was governor. Tellingly, the rate among Black infants, 12.7 per 1,000 live births, is more than twice that of white children, 5.2.

Now let’s turn to the Affordable Care Act, which was enacted in 2010, just as Haley took office as governor. Haley opposed Obamacare virtually from the outset, and gleefully. In July 2014, when a federal appeals court blocked Obamacare premium subsidies in states, such as South Carolina, that had not created their own ACA exchanges but left that task to the federal government, she celebrated.

“This is a huge blow to Obamacare as we know it,” she wrote on Facebook. “The way I see it, this allows the Supreme Court a redo. We can only hope!” (Her reference was to the 2012 Supreme Court decision that ruled the ACA constitutional.) The Supreme Court overturned the appeals court’s subsidy decision in 2015.

Haley flatly refused to expand Medicaid in South Carolina under the ACA. The state remains one of the 10, all Republican-controlled, that still haven’t expanded Medicaid. The consequences to its residents are marked. South Carolina’s health uninsured rate, 14.9%, was the 10th worst in the country, according to the Commonwealth Fund, below the national average of 12.1%. All the 10 worst states except Nevada are non-expansion states.

South Carolina also had the second-highest percentage of residents with medical debts recorded by credit bureaus in 2021, at 22.3%. Only West Virginia, with 24%, was worse. The failure to expand Medicaid undoubtedly plays a role in this record, for the program would relieve lower-income households of many medical bills.

Asked at a New Hampshire town hall broadcast in May about her refusal to expand the program, Haley responded with a word salad about job creation programs her state had sponsored, rather than on addressing the healthcare needs of lower-income residents.

“We focused on lifting up everybody, not just a certain amount,” she said. She said the job program she sponsored found work for 35,000 residents. What she didn’t say was that this figure was a fraction of the number of residents locked out of Medicaid eligibility. This “coverage gap,” as the independent healthcare research organization KFF defines it, is 166,000 in South Carolina. The Urban Institute placed the figure at 196,000 in a 2018 survey.

Haley doubled down on her opposition to Medicaid expansion during that New Hampshire town hall. “It’s easy and lazy to expand Medicaid,” she said, “because all you’re doing is giving people money to buy them time.”

Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley all want to repeal Obamacare. Their plan to replace it is not having any plan at all.

How penny-wise and plain foolish was her Medicaid policy as governor? Under the Affordable Care Act, the federal government paid 100% of the cost of expansion from 2014 through 2016. From 2017 on, the match was reduced bit by bit until it reached a permanent level of 90% in 2020. Even that is well above the federal match rate for traditional Medicaid, which is 69.67% for South Carolina.

In other words, Haley’s refusal to expand Medicaid was based not on empirical effects, for there is no disputing that Medicaid eligibility improves health outcomes for enrollees.

It was not based on state finances, for the residual state match even today is more than compensated by gains in the economic vitality of enrollees and the fiscal health of local hospitals that are economically dependent on Medicaid reimbursements. The only remaining rationale is ideological — Haley’s policy hewed close to the furthest-right position of the Republican Party.

In 2021, four years after Haley left office, her state was forced to come to terms with the consequences of its inattention to maternal health. A legislative panel detailed the toll on South Carolina mothers — finding that 62% of maternal deaths were pregnancy-related and 68% were preventable. The maternal mortality rate was 2.4 times higher for Black and other women of color than for white women (42.3 per 100,000 live births for Black and other women of color, compared with 18.0 for white women).

The state enacted one of the most important recommendations of the study panel, which was for Medicaid to cover 12 postpartum months rather than the existing cutoff at 60 days. The change went into effect in 2022. In this respect, at least, South Carolina joined 46 other states in extending Medicaid coverage for new mothers.

But Haley’s legacy lives on, in wretched figures on infant and maternal mortality and uninsured rates. She may be representing herself on the stump as new blood with a fresh outlook in comparison with Donald Trump, but her policies impose the same old GOP-style cruelty on Americans whose lives could be improved by a government that cares.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.