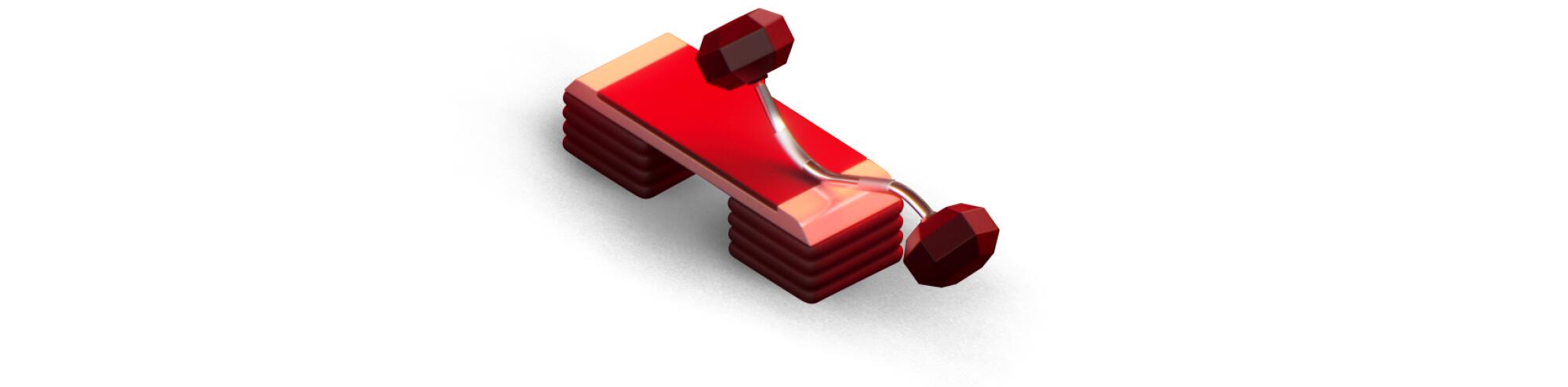

(Sean Dong / For The Times)

Arezu Aghaseyedjavadi signed up for her first Barry’s class in 2017, motivated to give the high-intensity workout a try after noticing how fit everyone seemed when she flew from San Francisco to Los Angeles for weekly work trips.

She lost 50 pounds in the first year and got hooked. More than 1,500 classes later, the venture capitalist, who now lives in Pasadena, pays about $500 a month for the boutique fitness chain’s top-level membership and has sweated it out at Barry’s around the world: all seven L.A.-area locations as well as studios in the Bay Area, San Diego, Austin, New York, Miami, Chicago, Boston, the United Kingdom, Dubai and Abu Dhabi — “I went there for 48 hours for a business meeting and I was like, ‘I want to get my Barry’s in,’” she said.

Aghaseyedjavadi was one of hundreds of Barry’s superfans who participated in a recent three-day bash to celebrate the brand’s 25th anniversary — a considerable milestone in the competitive, fad-of-the-moment world of health and fitness clubs, estimated to be a $98-billion global market.

To mark the occasion, the company rented a Hollywood film studio and set up free cold-plunge baths, facial stations, a Lululemon pop-up and zero-gravity Therabody Lounger chairs. Employees handed out packets of Liquid I.V. hydration powder and samples of Mosh, a line of protein bars by Maria Shriver and her son Patrick Schwarzenegger. The kickoff party, DJ’d by Diplo and attended by *NSYNC’s Lance Bass, stretched into the next morning.

The main event was a series of huge 225-person workout classes, for which the company trucked in $1 million worth of Woodway treadmills, 2,200 dumbbells and resistance bands, and a custom audiovisual system to replicate the neon-red, pulsating nightclub aesthetic that has become a staple of the Barry’s experience.

An hourlong adrenaline-racing workout in a windowless room with hundreds of panting strangers spaced inches apart was unfathomable a few years ago, when gyms and fitness studios abruptly closed at the start of the pandemic. In the chaotic months that followed, many — overwhelmed by ever-changing government mandates and unable to lure back COVID-anxious clients who’d switched to virtual or outdoor exercise programs — never reopened.

Founded in West Hollywood, Barry’s had become one of the most recognizable names in a crowded industry and was in the midst of an aggressive global expansion in early 2020. One hundred forty thousand people were attending a Barry’s class at least once a week, and the company planned to open 16 new locations by the end of the year, a 23% increase.

Instead, it halted operations at all 70 of its studios and laid off or furloughed two-thirds of its 1,300 employees.

“We were peaking — I call it the era of opulence,” Chief Executive Joey Gonzalez — ripped, toasty tan and typically tank-topped — said in a recent interview at Soho House Holloway. He started taking Barry’s classes in 2003 when he was an aspiring actor, became an instructor the following year and has led the company since 2015.

“Barry’s was so successful, we were firing on all cylinders, fitness in general had never been more top of mind for consumers,” he continued. “It was the most unnatural experience in life to go from generating over $100 million of revenue per annum to zero dollars.”

Big-box gyms, the Thighmaster and step aerobics dominated the American fitness landscape when personal trainer Barry Jay and two investor partners, John and Rachel Mumford, leased a small storefront at the corner of La Cienega Boulevard and Holloway Drive in 1998.

Jay didn’t have a military background — he’d previously worked as an instructor at Gold’s Gym — but called his new business Barry’s Bootcamp to highlight the hardcore nature of the workout, which he designed to be far tougher than the high-reps-with-light-weights body-sculpting classes that were popular at the time.

He leaned into the name: His studio was decked out in camouflage wallpaper and reinforced netting, and members were given numbered silver dog tags when they joined. During class, which cost $15 each and alternated between heart-pumping intervals on the treadmill and strength training with dumbbells on the floor, he would holler orders to sprint faster and lift heavier while pacing the darkened room in cargo shorts.

The punishment for being late was stair climbs or push-ups. Once, when Jay caught a client eyeing the clock, he got on a step stool and detached it from the wall.

“I said, ‘Hang on, Sandy, let me help you out. Why don’t you hold the clock while you run, and now you won’t have to worry what time it is,’” he recalled recently.

Jay, now retired and living in Las Vegas, had flown into L.A. to be a special guest at the 25th anniversary festivities. Sitting serenely on a treadmill before the start of the first 225-person workout, the company’s largest class ever (the average Barry’s class can fit about 50 people), he attributed some of his brash behavior back then to personal issues he was dealing with as he struggled to maintain his sobriety while teaching 40 times a week.

A 2006 Times profile detailed his problems with cocaine and other drugs, describing Jay as “an addict waiting to happen, with a more-is-more personality that made him do everything to the extreme ... A few would leave class in tears.”

“I’m very soft now,” Jay, 60, said. “There was a lot of me that evolved with each and every year. But I will say it was all done in the spirit of the workout.”

Barry’s itself evolved, slowly phasing out the boot camp part of its name and the intimidating drill sergeant teaching style.

In its place, it pivoted to a workout-as-elite-lifestyle hook that helped launch the era of the modern boutique fitness studio. A class was no longer just a fat-burning sweat session — it was an all-encompassing, and expensive, health and wellness journey that became part of your identity.

Gonzalez was behind the glow-up. Still teaching Barry’s classes, he persuaded the company’s co-founders to let him invest his own money to open the company’s second location, in San Diego, in 2009.

Two years later, he took out a second mortgage on his home to bring Barry’s to New York City, unveiling an upscale studio that would serve as the brand’s blueprint going forward: a sleek small-format space stocked with high-end bath products and other luxe amenities; top-of-the-line exercise equipment; a Fuel Bar selling pricey made-to-order protein shakes; and an army of absurdly hot instructors.

“It is inspirational and it is aspirational,” Gonzalez, 46, said of the rebranded Barry’s. “It just felt like the right thing to do. I think we were entering a new era where millennials don’t necessarily respond to that type of punitive behavior.”

The hyper-curated vibe combined with the company’s 50-50 mix of cardio and lifting caught on among designer-athleisure-clad women, gay men and celebrities including Kim Kardashian and David Beckham. In 2019, a spandex-bodysuited Jennifer Lopez tried out to become a Barry’s instructor in an SNL skit (“How do you think you get this way? I haven’t had a carb since I was a baby!”).

Boutique brands hinge on cult status — for those who are there, they can’t imagine being anywhere else.

— Simeon Siegel, managing director at BMO Capital Markets

Rivals copied its high-energy format and feel, leading to an explosion of lookalike studios around the world selling their own take on premium high-intensity interval training (HIIT). There are now brands that combine rowing and weights, StairMaster and weights, climbing and weights, boxing and weights, spinning and weights, treadmill-rowing-and-weights, and so on, and major gym chains have introduced boot-camp-style workouts to their class schedules.

Whichever studio you choose, it’s a near-guarantee that the playlists will be heavy on Britney and Beyoncé, the walls selfie-ready and cheeky-hashtag-adorned, the core customer base made up of die-hard fanatics reverse-lunging and dead-lifting in branded merch.

“Boutique brands hinge on cult status — for those who are there, they can’t imagine being anywhere else,” said Simeon Siegel, managing director at BMO Capital Markets. “People are proud to describe their experiences — they don’t just say they worked out; they tell you where they went.”

Despite the higher price point compared with traditional gyms — a single Barry’s class in L.A. now costs $34, and classes were shortened a few years ago to 50 minutes from an hour — “boutique fitness enthusiasts willingly pay a premium,” an October report by Research and Markets said.

“The boutique fitness industry is experiencing remarkable growth, with the global market projected to reach a staggering $79.66 billion by the end of 2029, as compared to $48 billion in 2022,” the data analysis firm said. It attributed the surge in popularity to factors including a sense of community, small class sizes and the trendy, meticulously cultivated atmosphere.

During the pandemic, many fitness operators simply unplugged their cardio machines, locked their doors and waited it out. Barry’s closed all of its Red Rooms in the U.S. on March 16, 2020, but Gonzalez wanted to find ways to keep the business going.

The next morning, he led a live full-body workout over Instagram that drew more than 20,000 participants, a precursor to the Barry’s At-Home virtual group classes that the chain would begin to offer a few weeks later. To help quarantined customers build their personal workout stations, and to make some money during the shutdown, Barry’s sold its branded weights, exercise benches, mats and resistance bands online.

Fitness really got the short end of the stick. There seemed to be support for so many different industries, but nothing for fitness.

— Joey Gonzalez, Barry’s CEO

Many iterations would follow: There was Barry’s X, an app-based workout for clients to do on their own. It debuted Barry’s Outdoors, its silent-disco strength classes held in parking lots, on rooftops and in the parking garage of the deserted Beverly Center; clients worked out in masks spaced six feet apart, wore wireless headphones to hear the instructors and had to wait in between rounds while employees sanitized each station. In New York, Barry’s reopened a couple of its studios as “open gyms” where people could work out with a remote instructor’s voice piped in through speakers.

When the company was finally given the green light to turn on its red lights again, it held indoor classes at 25% or 50% capacity.

“This was no fault of ours, so it was really challenging to process, internalize and problem-solve,” Gonzalez said of that strange time. “Fitness really got the short end of the stick. There seemed to be support for so many different industries, but nothing for fitness.”

Due to its size, Barry’s was not eligible for PPP loans. But it did receive incentives from Miami Mayor Francis Suarez and moved its headquarters to the city, where Gonzalez lives, in 2021.

Barry’s, with financial backing from private equity firms North Castle Partners and LightBay Capital, has been in rebuilding mode ever since the most stringent government restrictions were lifted. Today it has 84 studios in 14 countries, just shy of where it had planned to be at the end of 2020, and employs 1,400 people, its largest workforce to date.

Its pace of expansion has been slower and more deliberate than that of franchise giants such as Orangetheory Fitness (more than 1,500 studios in 25 countries) and Xponential Fitness, a group that owns CycleBar, Row House and several other boutique brands. More than half of Barry’s studios are corporate-owned.

Revenue and attendance were up about one-third last year compared with 2022, the year Barry’s became profitable again. Roughly 20% of its clients take three or more classes a week, and 3 million people have tried the Barry’s workout since its inception. Just over half of its clients are 28 to 45 years old, about two-thirds of them female, the company said.

Now Barry’s is looking to double the size of its portfolio in the next five years, and making big investments in the L.A. market, where it already has a significant presence.

Next month Barry’s will close its original West Hollywood studio, a run-down outlier at more than a quarter-century old, and move into a gleaming 21,000-square-foot space a few blocks away. It’s bringing a concept called Ride X Lift to the new studio — the low-impact workout combines spinning and weights and is designed for people who dread the tread. There are also studios coming to Santa Monica, Studio City and Newport Beach in the first half of the year.

The pandemic led to a forced consolidation toward larger, well-capitalized fitness brands, but it’s still an extremely fragmented industry with a lot of players and high attrition rates, Siegel of BMO said.

“The best fitness products that are not winning on price are winning because of an emotional connection that is as strong as the physical one,” he said.

It has also become a more expensive business to run, so the pressure is on to get notoriously fickle customers in the door and convert them into fervent regulars like Aghaseyedjavadi.

“One time I did three classes in one day: a 6 a.m. and a 7 a.m., then I went to work, then there was traffic in L.A. so I was like, ‘Let me just go do a Barry’s at night,’” she said.

“It was the same instructor from the morning. He saw me and was like, ‘You’re back?’ I was like, ‘Should I do a fourth class?’ And he’s like, ‘No, please go home.’”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.