Column: Businesses keep complaining about shoplifting, but wage theft is a bigger crime

Former Home Depot Chief Executive Bob Nardelli went on Fox Business the other day to warn that a surge in shoplifting by organized gangs showed that America was descending into “a lawless society.”

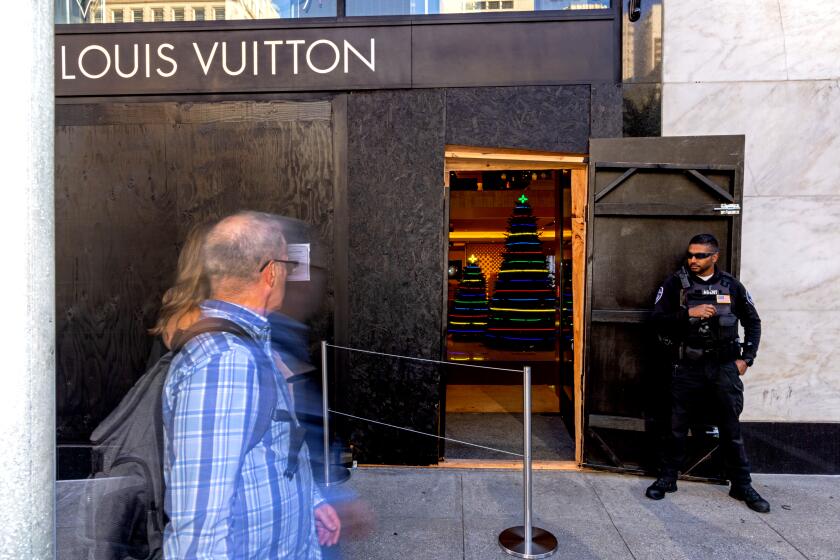

“We’ve got to get this back under control,” Nardelli intoned gloomily, after videos of smash-and-grab teams in retail stores had spooled behind him. “I fear where this is headed.”

There isn’t much to say about Nardelli’s sepulchral comments, other than that he has a hell of a nerve.

Selective reporting of retail theft incidents by retailers and skewed media coverage of retail theft (has) tended to focus on sensational incidents that feature violence or brazen daytime theft operations.

— National Retail Federation tells the truth about the shoplifting crisis

Back in June, Nardelli’s former company settled a class-action lawsuit with workers alleging widespread wage theft for $72.5 million.

More than 885,000 Home Depot workers were members of the various classes, including those who were locked in their stores off-the-clock following the day’s closing shift until a supervisor got around to letting them out. Home Depot didn’t admit to the allegations, and said it had settled merely to make the lawsuit go away.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Juxtaposing Nardelli’s remarks and the settlement points to the discordance in how we define “crime” in the workplace. On the one hand, sporadic robberies inflated by retail lobbyists and media via eye-catching reports; on the other, the pervasive shortchanging of hourly workers by their employers.

Estimates of the scale of both phenomena are all over the map, but run into billions of dollars a year. Yet it’s reasonable to conclude that, in terms of the direct impact on households, wage theft is the bigger deal.

Let’s take a look, starting with what retailers call “shrink.”

The term covers three categories of loss: First is “external theft,” such as individual shoplifting and organized retail crime exemplified by those mass invasions of shops by gangs. Then there’s internal theft — pilferage or embezzlement by employees. Finally, what retailers call process and control failures, such as paperwork glitches and other mixups that result in their losing track of inventory.

It’s the first category that gets all the attention, thanks to those video reports so popular on cable and local news shows, and to corporate executives trying to blame their inventory shortfalls on outside parties beyond their control, rather than breakdowns in their internal systems.

Hundreds of workers have died from extreme heat, but business lobbyists insist government rules aren’t necessary. Workers’ best hope for protection: unions.

A survey published last year by the National Retail Federation attributed 37% of all “shrink” to external theft, but more than 54% to those two internal categories.

Yet executives talk as though external theft is the whole ballgame. They lobby local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to pump up their efforts against it — and largely succeed.

As it happened, an independent study commissioned by the NRF itself acknowledged that the public’s perception of the scale of organized retail theft has been distorted by “selective reporting of retail theft incidents by retailers and skewed media coverage of retail theft,” which has “tended to focus on sensational incidents that feature violence or brazen daytime theft operations.”

Industry groups and politicians are sounding alarms over the thefts. But in some cases, the statistics they cite are inflated or flat-out wrong.

The panic inspired by these reports has gone on for years, as my colleague Sam Dean documented in 2021. Dean showed that retail groups’ estimate of $70 billion lost annually to organized thieves was conjured out of thin air. The NRF last year raised its estimate to $94.5 billion for 2021.

That feeds the claim commonly heard these days that the level of organized theft has reached “unprecedented levels” (to quote a recent report by ABC News). But it’s based on very misleading math.

As a percentage of total retail sales, “shrink” has barely budged. The NRF estimated it at 1.4% of retail sales in fiscal 2021, the latest year available. That’s exactly what it was in fiscal 2016. The percentage edged up to 1.6% in fiscal 2019 and 2020 before falling back down.

Total retail sales, however, have risen inexorably, according to the Census Bureau, from about $6.2 trillion in 2019 to $7.4 trillion in 2021 and $8.1 trillion in 2022. That means that retail theft will continue to reach “unprecedented” levels in absolute terms even if its percentage of total sales doesn’t change.

It’s not unusual for corporate leaders to play games with these figures to distract investors. Dick’s Sporting Goods, which is often cited as a victim of organized theft rings, said its gross profit for the second quarter of this year that ended July 30 fell “in large part to the impact of elevated inventory shrink, an increasingly serious issue impacting many retailers,” as CEO Lauren Hobart put it.

The company’s quarterly earnings report, however, explained that only about one-third of the decrease in its quarterly profit margin was due to “inventory shrink.” Most of the rest was due to larger discounts on merchandise — another issue “impacting many retailers” that had saddled themselves with excess inventory after misjudging consumer demand.

Republicans are bowing to industry lobbyist in loosening state child labor laws. The inevitable result will be a rise in child deaths in the workplace.

Another factor in the elevation of retail theft into an all-consuming “crisis” is partisanship. Nardelli’s comments are a perfect example. He used his Fox Business appearance to blame the problem on — no surprise here, given the forum — President Biden.

“We have a crushing inflation and a crippling interest rate in this economic environment that this administration has put us under,” he said.

Nardelli, who is also a former CEO of Chrysler, also groused about unions seeking higher pay, in case you were wondering where he’s coming from.

Nardelli was especially exercised by the recent contract settlement between United Parcel Service and the Teamsters, which he said was going to “inflate inflation.... When wages are going up, package costs will go up.” He mentioned a contract provision requiring UPS to equip its trucks with air-conditioning. “That’s going to be another increase because of fuel costs,” he said.

Better, in the Nardelli and Fox world, to have drivers broiling to death in their trucks to keep your delivery costs low.

That brings us to the other side of the coin on workplace crime, wage theft. That’s been estimated as high as $50 billion a year by the Economic Policy Institute, which extrapolated from a 2008 survey of low-wage front-line workers in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York.

Employers use a multitude of methods to steal wages. They may pay workers less than the legal minimum wage, fail to pay overtime, deny workers legal meal breaks or rest periods, divert workers’ tips, or require them to work off-the-clock to prepare for their shifts or to perform duties after their shifts have ended.

A glaring new technique is the misclassification of workers as “independent contractors” rather than employees, thus sticking the workers with expenses that would be covered for employees. Uber, Lyft and other gig companies have perfected this practice and made it the bedrock of their business model. But it’s properly regarded as wage theft.

In 2019, when the gig companies drafted Proposition 22 to overturn a California law mandating that their drivers and delivery workers be treated as employees, they claimed that it would guarantee an hourly pay scale of 120% of the state’s minimum wage.

That came to $15.60 an hour in 2019, based on the state minimum wage of $13, and $18.60 this year, when the minimum wage is $15.50.

As Ken Jacobs and Michael Reich of the UC Berkeley Labor Center determined, however, the loopholes written into the measure — exemptions for driver waiting time, underpayments for gas, vehicle wear and tear and insurance, and the cost of Social Security and Medicare taxes — reduced the actual hourly compensation for Uber and Lyft drivers to an average of $5.64 an hour.

The Fed has ignored how corporate profits drove inflation. That left PepsiCo, Tyson Foods and Procter & Gamble free to jack up prices and blame it on the pandemic and Ukraine war.

The flash mob shoplifting sprees obviously are concentrated in the retail sector, but wage theft can be perpetrated by any business, large or small.

It’s not uncommon for accusations to be laid against franchise businesses. But Amazon, which operates only a handful of retail stores, last year settled wage-theft allegations by warehouse workers in Oregon for $18 million and paid $61.7 million in 2021 to settle a Federal Trade Commission accusation that it stiffed gig-based delivery drivers.

The FTC alleged that Amazon cut the hourly pay originally promised the drivers without giving them adequate notice and diverted tips that customers paid, which the company had said would flow 100% to the drivers. The $61.7 million was “the full amount that Amazon allegedly withheld from drivers,” the FTC said. After the FTC opened its investigation, Amazon restored the original pay scale.

Other big companies that have settled wage-theft claims including Walmart, which led the roster of settlements with $1.4 billion in payments from 2000 to 2018, followed by FedEx, at more than $500 million, according to the advocacy organization Good Jobs First.

Other legal settlements involved companies not commonly thought of as employers of low-income workers, such as Bank of America ($382 million in 2000-18 penalties according to the Good Jobs First survey), Wells Fargo ($205.4 million) and JPMorgan Chase ($160.5 million). These firms’ marquee workers tend to be well-paid professionals, but they’re supported by legions of back-office clerks and other workers paid by the hour.

Billions of dollars a year are returned to cheated workers, but it’s at best a smidgen of what they’ve lost. Wage theft is a flagrant violation of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, but enforcement has been systematically hampered by the business lobby in Congress.

Indeed, the aggressive actions by former Labor Department official David Weil to protect the wages of working people from thievery that led last year to the Senate rejection of his nomination by Biden to return to the agency’s Wage and Hour Division.

As I wrote after Weil was forced to withdraw his name from consideration, he had come under ferocious attack by business interests and Republicans from the start, because they knew of his commitment to enforcing the labor laws on the books and the court rulings that have upheld them.

The division’s budget had been “flatlined for more than a decade,” Weil told me then, not even counting the impact of inflation.

Measuring the Wage and Hour Division’s workforce in the past against its payroll today and considering the vastly greater number of workers and workplaces within its jurisdiction, Weil estimated that the division in 1940 had 64 times the capacity that it has now to investigate violations.

Compare that with the enthusiasm that officials in Washington and state governments muster to fight flash-mob robberies with more police, focused investigations and tighter laws. If you’re a big business, your exaggerated complaints get heard at the highest levels. If you’re a working man or woman being nickel-and-dimed by unscrupulous employers, you’re on your own.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.