Children shrieked and splashed in the water, and a couple on an anniversary staycation floated at the edge of the hotel pool, nursing their blended beverages.

Alea Britain had checked into Hotel Maya the night before and was planning to spend Friday jet skiing with friends. Nothing appeared out of the ordinary since Britain had arrived at the waterfront Hilton property overlooking the Long Beach skyline.

“I had no idea there was a strike,” she said. “I haven’t noticed anything.”

But a few hours later, it was unmistakable — drums, megaphones, striking workers marching to demand higher wages and better working conditions.

“Our fight is to keep a roof over our heads,” shouted union leader Ada Briceño, speaking for the 15,000 hotel employees striking for a new contract. “We are, right now, one paycheck away from homelessness. We are, right now, living in our cars.”

Forty days since the rolling strikes began, this had become the defining tableau of L.A.’s summer of labor — workers chanting in red T-shirts as guests, some appearing perplexed, others a bit sheepish, lug their suitcases past them and into the lobby.

The writers’ and actors’ strikes will take a while to reach consumers still enthralled by “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer,” blockbusters finished before the twin work stoppages in Hollywood. But the series of hotel walkouts, which began during the busy weekend before the Fourth of July, hit travelers right away.

This summer, tourists visiting Disneyland, the Anime Expo and the L.A. leg of Taylor Swift’s Eras tour have often been greeted outside their hotels by picketing workers represented by Unite Here Local 11. But because the strikes have happened in waves, targeting hotels in different regions on different days, some tourists, even those who see themselves as ardently pro-union, haven’t always known quite how to respond.

Hotel strikers have endured violent incidents involving security personnel at three hotels in L.A. and Orange counties, the union said in a complaint.

The union sent out a news release this week asking people to boycott three hotels where violence had flared against strikers, including Hotel Maya, where a picketer was recently punched in the head during a chaotic altercation at a wedding. But before that, the union had adopted a distinctly quieter stance, merely listing the hotels without contracts on its website and asking that people “not patronize” them.

Although some Southern California hotel customers did change their plans, others — especially those visiting from out of town — said they either didn’t know about the strike or had booked nonrefundable stays ahead of time. In online reviews for the hotels targeted for strikes, several guests vented frustrations with both hotel management and picketing employees in the contract dispute.

“If you want to have a peaceful vacation choose another location,” wrote a tourist who stayed at 1 Hotel West Hollywood in August.

“Pay your workers!” wrote another, who left a 2-star review for the Holiday Inn Los Angeles LAX Airport, noting that protesters showed up around 5 a.m. “I know that workers don’t want to do this and don’t want to disturb guests, but they’re left no choice.”

Another visitor, who stayed at the hotel while in town to see Swift, criticized what she called “abrupt behavior” from the strikers and complimented the hotel for blaring Swift’s music to drown out their chants.

“This is awesome customer service,” she wrote. (The hotel responded: “We truly appreciate your wonderful comments!”)

Emma Eblen was on her couch recovering from COVID-19 and scrolling through email when she spotted a subject line that said “Congrats!”

When she was finally convinced it wasn’t a scam, the 30-year-old began to shake with excitement and dialed her friend with the news: She’d won a pair of tickets to see Swift in L.A. through a giveaway hosted by Capital One. They immediately searched for hotels and chose the Los Angeles Airport Marriott because a chartered bus could pick them up there and take them to the stadium.

It was a bit odd that the hotel reservation was nonrefundable, she recalled thinking at the time, but for two nights at around $800, the friends decided it was their best bet. It wasn’t until a week before the trip, while searching a Facebook group for concertgoers, that the Olympia, Wash., resident learned of the strike.

“Oh, my God,” Eblen thought, her mind immediately jumping to her parents, both members of a theater union. “Crossing a picket is one of the worse things I could ever think of.”

But there were almost no options left on Airbnb, and she knew she couldn’t afford to eat the cost of the nonrefundable reservation. Winning the tickets had felt like a dream — she couldn’t stop thinking about her 15-year-old self crying along to “Teardrops on My Guitar” on the radio years earlier — but now she felt sick with guilt at even the thought of crossing a picket line.

In the end, it never came to that; although other hotels in the Marriott chain were picketed, hers was not. Still, she said, she’d been awakened by 6 a.m. chants from picketers at a hotel across the street.

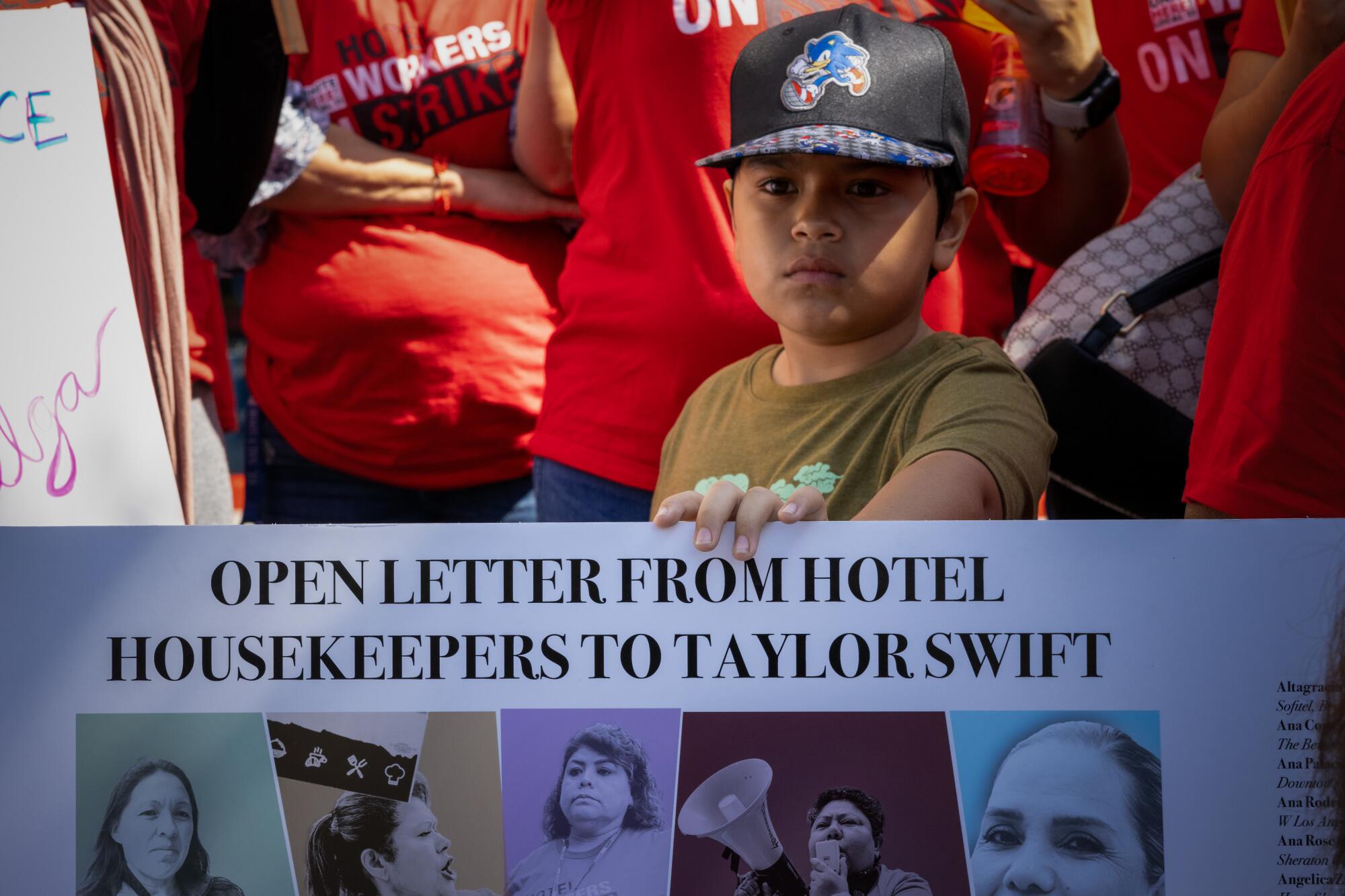

As part of its strategy, the union has targeted events expected to draw thousands to the region, including the annual meeting of the American Political Science Assn., and Swift herself.

In a plea to the pop icon, whose out-of-town fans boost hotel prices in the cities she visits, the union borrowed the name of one of her albums. “Speak Now!” their letter reads, “stand with hotel workers and postpone your concerts.”

As L.A.’s hospitality industry welcomes Taylor Swift’s Eras tour and the business it will bring, striking hotel workers called on the pop star to join their cause.

A few days after releasing the public letter to Swift, whose six sold-out concerts went on as planned, the union again drew headlines, filing a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board highlighting what it called a pattern of violent incidents and property destruction at picket lines. It specifically listed the three hotels it has now asked people to boycott — Hotel Maya, Fairmont Miramar in Santa Monica and Laguna Cliffs Marriott Resort & Spa in Dana Point.

In late July at the Dana Point hotel, Maria Hernandez, who works as an assistant server at the hotel’s Knife Modern Steak restaurant, said she spotted celebrity chef John Tesar, who runs the restaurant, walking toward the picket line. She began recording on her cellphone as he walked toward her and flipped her off.

“Take your union, and shove it up your,” he says, punctuating his delivery with an expletive and then hurling an insult at her in Spanish. “You’re a bad person. You’re a lazy pendeja.”

After that, Hernandez said, he snatched a drumstick out of her hands. She told him she knew who he was and that what he was doing wasn’t right, she said, and he then told her that he would recognize her when she came back to work.

“I was afraid,” she said, “that I would get into trouble or get fired.”

In an interview, Tesar said that while staying at the hotel during a vacation with his three children — 12, 5 and 2 — protesters had jeered at, filmed and made hand gestures toward him and his children, calling him a “terrible person.” In the days since then, he said, he’s received several death threats and been called a racist.

The former “Top Chef” contestant acknowledged that, after a protester flipped him off on the last morning of his stay, he used a metal spoon to break the picketer’s drum.

“I was protecting my children,” he said. “I’m anything but a racist. … I’m a New Yorker, I’m sorry, I speak in profanities. I’m a chef. We curse in the kitchen. I apologize if it offended anybody.”

After Maisha Hudson and Shawn Parker got engaged, the bride-to-be reached out to a wedding planner she knew from her college sorority, who sent over a list of potential venues.

Intent on a waterfront view, the Inglewood couple picked Hotel Maya, and in January, six months before the strike began, the couple signed a contract and put down a deposit to reserve their August date, according to interviews with Maisha Hudson-Parker, as she’s now known, and her wedding planner, Deborah Croom.

It wasn’t until Aug. 1, four days before her ceremony, the bride said, that she learned from the hotel that there might be strikers there on the day of her wedding. With friends and relatives flying in from across the country, shifting to a different location on short notice felt impossible — friends had scrambled to move a wedding in 72 hours last year, she said, and ended up paying $70,000.

Hotel managers apologized for the inconvenience, Hudson-Parker said, but assured her she wouldn’t be able to hear anything because the picketers often gathered in the front of the hotel, not at the back of the property near the water, where the ceremony would take place.

Not long after sunrise on her wedding day, she woke to the sound of bullhorns, and the hotel offered to move the ceremony into an indoor ballroom. But it would have been a tight squeeze for her 226 guests, the bride said, and she’d picked the venue specifically for the outdoor view of the water.

Instead, the hotel put up mobile metal fencing to block the outdoor ceremony area from a publicly accessible pathway along the shoreline. Before the ceremony, the bride said, a few of her guests asked the striking workers if they’d mind pausing their picket for 30 minutes so the couple could exchange vows in quiet. They refused, she said, leaving her and many of her guests — among them union members and supporters — in an unenviable position.

The bride said she’d donated water bottles during the Los Angeles teachers’ strike and had friends in the writers’ strike. Croom said she spent much of the day thinking of her parents, who were union members — her mother a teacher, her father working in the shipyards — and heard their voices in her head: “You should never cross the picket line.” But by the time they learned the venue was one of the locations to be picketed, both women said, payments had already been finalized and guests were preparing to fly out.

On the afternoon of the ceremony, as guests mingled in the outdoor plaza decorated with bouquets of burnt orange and crimson flowers, smooth music crooning from the speakers competed with the sound of drums and picketers chanting, “Hotel Maya, escucha, estamos en la lucha.” (Hotel Maya, listen, we are in the fight.)

Los Angeles is sitting at the vanguard of two trends: increasingly expensive housing and an increasing amount of cross-union solidarity.

Frustrated, wedding guests began to record videos of the picketers gathered on the other side of the fencing. “They’re trying to mess up her wedding,” one guest says in a recording shared with The Times.

Another clip shows a moment of commotion, as the mobile fencing gets hoisted into the air and people rush toward it from both sides. On the other side of the fence, a man in a black shirt — described by the union in a tweet as a hotel guest — runs up to a picketer and pummels him on the side of the head.

Carlos Cheverri Canalés, the worker who was punched, said in an interview that he thinks he lost consciousness briefly because the next thing he remembered was waking up to shouts. Recently hired as a line cook in the hotel’s lounge, he said he didn’t yet have health insurance and was worried about medical bills.

“I was punched in the head,” he said, “for trying to have a voice.”

Another worker on the picket line that day, David Ventura, said he saw security guards, at the direction of a nearby manager, abruptly lift the chain link fencing, ramming it toward the workers. Worried that people might get knocked over, the bellman said he rushed forward to help his co-workers.

“I was trying to take care of my people,” he said. “It would behoove the owners to do right by us at the bargaining table.”

In a statement, the Long Beach Police Department — whose officers arrived at the scene and eventually escorted the bride, in her flowing, ivory-colored gown, into the ceremony area — said that four demonstrators were injured by a man who also destroyed a speaker. Police said the suspect, whom the bride said she didn’t know, fled before police arrived.

At one point, the bride said, she had tears in her eyes and asked a protester to please respect her wedding. “He yelled at me,” Hudson-Parker said, “and told me I should have known this was coming.”

The ceremony started an hour and a half late, which squeezed the timeline for photos and cost her the time to dance with some of her elderly guests who left once it got dark.

What’s happening now feels different. There’s a level of cross-union support across radically different workplaces, along with a knowledge of one another’s respective struggles, that I’ve never seen, or frankly ever thought possible.

The hotel has apologized, Hudson-Parker said, acknowledging it wasn’t properly prepared. The hotel’s director of human resources did not respond to requests for comment, and two other executives declined to comment. In an email about the incident to elected officials, Heather Rozman, president of the Hotel Assn. of Los Angeles, wrote that “guests had to be protected by both hotel security and Long Beach Police because of threats leading up to the wedding ceremony.”

Asked about the incident, a union spokesperson contended that workers were fully within their rights to protest by the wedding and that guests frustrated or inconvenienced by the strike should focus their blame on management.

“It’s the hotel’s responsibility,” spokesperson Maria Hernandez said.

During the protest at the hotel almost a week later, picketers unfurled a bold red banner reading “Boycott.”

As the workers marched in circles, volunteers from the National Lawyers Guild’s legal observers program, called as a precaution by the union after the wedding altercation, meandered through the crowd with notebooks. Off to the side, several hotel managers and executives watched.

Jesus Grimaldo, 79, who has worked at Hotel Maya for nearly four decades, addressed the crowd in Spanish. His health is failing — he’s a cancer survivor twice over and recently had a heart attack — but he can’t afford to retire, he said, because his $20-an-hour wage is too low. He supports his wife, as well as his daughter and grandchild, who live with them.

“What we are asking for,” he said, “is fair and just.”

A few guests observed from the lobby.

One of them, Christopher Ricci, who was in town for a convention put on by Kawai Pianos, owns a small piano store in Rhode Island. The brief boost in profits sparked by people’s COVID-19 lockdown-era hobbies had long ago disappeared, he said, and business was again on the decline.

“I feel empathy for them,” he said of the striking workers. “The way things are with inflation, you’ve got to try to pay people what they deserve.”

Earlier in the day, Cecilia Morones, part of the pair celebrating their anniversary with a staycation, said although she hadn’t known about the strike before arriving, she’d noticed some details that didn’t seem on par with other Hilton-brand hotels she’s stayed at in the past — the room was a bit dusty, the hot tub seemed over-chlorinated and the staff had been brusque.

She was considering mentioning something at checkout, she said, but for now she was trying to enjoy her vacation.

“It’s my anniversary,” she said, “do I really want to spend time talking to the manager?”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.