Column: Conservative attacks on abortion depend on a law that courts have snubbed for 150 years

Nothing reflects that show-stopping lyric “everything old is new again” like the tactics of the antiabortion movement — specifically, its reliance on a long-discredited 1873 law to eviscerate women’s healthcare rights in the modern age.

The law is the Comstock Act, which Congress passed during the post-Civil War period of puritan reaction at the behest of one of the outstanding bluenoses of American history.

The law drafted by Anthony Comstock, passed by Congress and signed by President Grant, outlawed the mailing of any “obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, print or other publication of an indecent character ... or any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion.” Penalties ranged up to 10 years.

The Comstock Act plainly forecloses mail-order abortion in the present.

— U.S. District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, citing a law from 1873

By any measure, the law is an antique. Yet it was cited in the April 7 ruling by Trump-appointed federal Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk reversing the Food and Drug Administration’s 20-year-old approval of the abortion drug mifepristone.

Kacsmaryk’s conclusion that the “plain text” of the act renders mailing the drug illegal was viewed kindly by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which temporarily stayed his ruling but observed that it may weigh in favor of the antiabortion activists who brought the case challenging the FDA.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

(The appellate court held a hearing in the case Wednesday in which the three GOP-appointed judges on the panel overtly favored the antiabortion side. The Comstock Act issue came up only once, briefly, but the FDA’s lawyer maintained only that issues other than the agency’s drug-approval process aren’t relevant.)

There are indications that antiabortion activists, if they prevail in this case, might try to exploit the Comstock Act to interfere with the shipment not only of mifepristone but of any drugs, equipment or paraphernalia that could be used for abortions.

A literal, 1870s-era reading of the act might even bar advertising or information about abortion, and could be used to restrict contraceptives.

The law went through numerous alterations on its way to enactment, however, and has been consistently narrowed over the subsequent 150 years by federal court rulings and congressional revisions. A Justice Department analysis last year drew on this history to declare that using the law as an antiabortion tactic runs directly counter to legal precedent.

The Comstock Act’s role in the case now before the federal courts warrants taking a closer look at its creator and its context.

As an anti-obscenity crusader, Comstock had the backing of wealthy patrons. They included Morris K. Jesup, a banker and philanthropist best known as a founder of the American Museum of Natural History, but who also co-founded the Committee for the Suppression of Vice, which Comstock chaired.

Trump-appointed judges in Texas are stripping all Americans of their rights to healthcare and safety. At last, the Biden administration is pushing back.

Another was Samuel Colgate, whose soap manufacturing company became the target of a years-long boycott launched by “freethinkers throughout the country,” according to Comstock biographers Heywood Broun and Margaret Leech.

Comstock first swam into public attention with a campaign against the spiritualist and women’s rights activist Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin. The pair had established the first Wall Street brokerage owned by women in 1870 (though it was bankrolled by Cornelius Vanderbilt, a lover of Tennessee and a devotee of the sisters’ spirit communications). Woodhull later ran for president on a platform that included free love.

Comstock brought a federal lawsuit against the sisters over reports they published in their weekly newspaper about a scandal involving the eminent clergyman Henry Ward Beecher, who was accused of an adulterous affair with a friend’s wife. In time, Beecher was exonerated in court and by his Congregational church elders, and the obscenity case against the sisters was dismissed.

The case, however, made Comstock’s name synonymous with “prudery, Puritanism and officious meddling,” according to Broun and Leech. Proving the adage that no publicity is bad publicity, Comstock would ride his renown to greater fame.

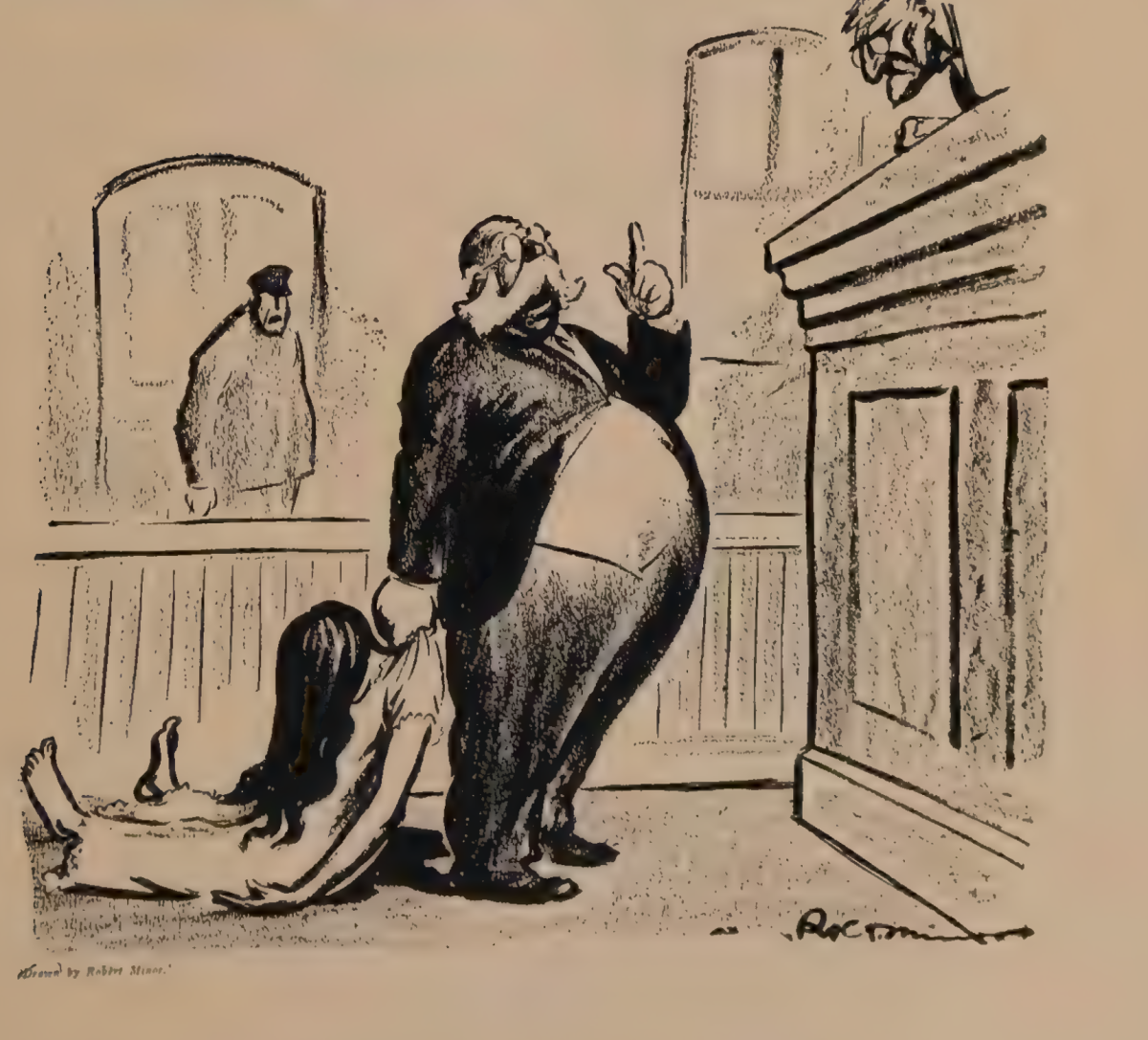

Due to his aggressive and often theatrical attacks on booksellers and publishers, Comstock also became a figure of public ridicule. He drew brickbats from none other than George Bernard Shaw after trying to shut down a New York production of Shaw’s “Mrs. Warren’s Profession.”

In that play, Shaw depicted prostitution not as a moral failing but — as he wrote in his preface to the work — a result of “underpaying, undervaluing, and overworking women so shamefully that the poorest of them are forced to resort to prostitution to keep body and soul together.”

Even the mention of prostitution and brothel-keeping offended Comstock’s sensibilities, though he never attended or even read the play.

“Comstockery is the world’s standing joke at the expense of the United States,” Shaw commented. “Europe likes to hear of such things. It confirms the deep-seated conviction of the old world that America is a provincial place, a second-rate country town civilization after all.”

(“I never heard of him in my life,” Comstock said of Shaw, according to the newspapers. “Never saw one of his books, so he can’t be much.”)

Comstock’s main targets in drafting his law were obscenity and pornography. He was also an antiabortion crusader, so he threw a ban on the mailing of drugs or materials used for abortion into the draft as a secondary matter.

Congress passed the law in March 1873, acting hastily and without extended discussion, in part because it was distracted by the Credit Mobilier case, a scandal that embroiled numerous representatives and senators in accusations of bribery by railroad investors.

The law Congress originally passed referred to “unlawful” abortions, but that qualification disappeared from a restatement of the law in 1948.

Almost immediately after the law’s passage, Comstock was appointed a special agent of the post office, which allowed him to step up his campaigns against obscenity and abortion.

By capitulating to antiabortion forces and showing its cowardice, Walgreens abandons its own customers and its corporate principles.

Judges and juries ruling on anti-obscenity complaints brought by Comstock often were flying blind, for the material in question could not be mentioned or displayed in court during those oversensitive times. Therefore, they had to rely on prosecutors’ descriptions of what was so offensive.

Any hint of nudity in a picture displayed in a shop window, even in a classical artistic context, was likely to attract a Comstock demand for its removal or lead to a prosecution.

Looking back on his career just before his death in 1915, Comstock boasted of having “convicted persons enough to fill a passenger train of 61 coaches,” and having “destroyed 160 tons of obscene literature.” Among his targets were some volumes deemed classics of European literature even then, including Bocaccio’s “Decameron.”

“Many of these stories,” he wrote, “are little better than histories of brothels and prostitutes, in these lust-cursed nations.” The result of exposure to such material was “a putting of vile thoughts and suggestions into the minds of the young, sowing the seeds of lust.”

However, “Comstock had no great luck among the so-called abortionists,” Broun and Leech found, achieving a lower percentage of convictions than against accused pornographers. When he did win a case, judges tended to levy small fines and no jail time.

As time passed, the environment in which the Comstock Act was passed came to seem almost quaint. Courts eventually overturned the provisions related to written and published works on 1st Amendment grounds. Congress removed the restrictions on mailing contraceptives in 1971.

Further court rulings established that the strictures on the shipping of abortion-related materials required that the senders intended that the recipient would use them unlawfully — that is, for abortions where that procedure was illegal.

That issue never came up after the Supreme Court’s Roe vs. Wade ruling in 1973 made abortion legal nationwide. Even after the court overturned Roe vs. Wade with its decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization last year, the Justice Department noted in its analysis, since mifepristone has nonabortion uses and since even states with the strictest antiabortion laws allowed the procedure to save the life of the mother, it would be almost impossible to establish that a sender intended that it be used unlawfully. In other words, the Comstock Act was effectively unenforceable.

As I’ve reported before, court rulings in 1915, 1930, 1933, 1936, 1938, 1944 and 1962, and congressional revisions in 1945, 1955, 1958, 1971 and 1994, relegated the original language of the Comstock Act to the dustbin.

The U.S. Postal Service has accepted the narrowed interpretations in its own administrative proceedings and presented its position explicitly to Congress, which never objected.

Judge Kacsmaryk willfully ignored all those years of statutory evolution in ruling that “the Comstock Act plainly forecloses mail-order abortion in the present.”

It might have been safe to assume that not even the most obdurate antiabortion conservatives could expect to resurrect the act and turn the clock back to the Comstockian world of 1873.

That might not be a safe assumption anymore, since the case appears destined for Supreme Court review. Since the current Supreme Court has shown no compunctions about disrespecting precedents of long standing, when it comes to women’s healthcare we may yet find ourselves transported back to the 19th century.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.