Column: Publishers and media watchdogs are struggling with an onslaught of AI-written content

After 17 years as the publisher of short science fiction and fantasy stories at Clarkesworld, the online and print magazine he founded in 2006, Neil Clarke had become adept at winnowing out the occasional plagiarism case from the hundreds of submissions he receives every month.

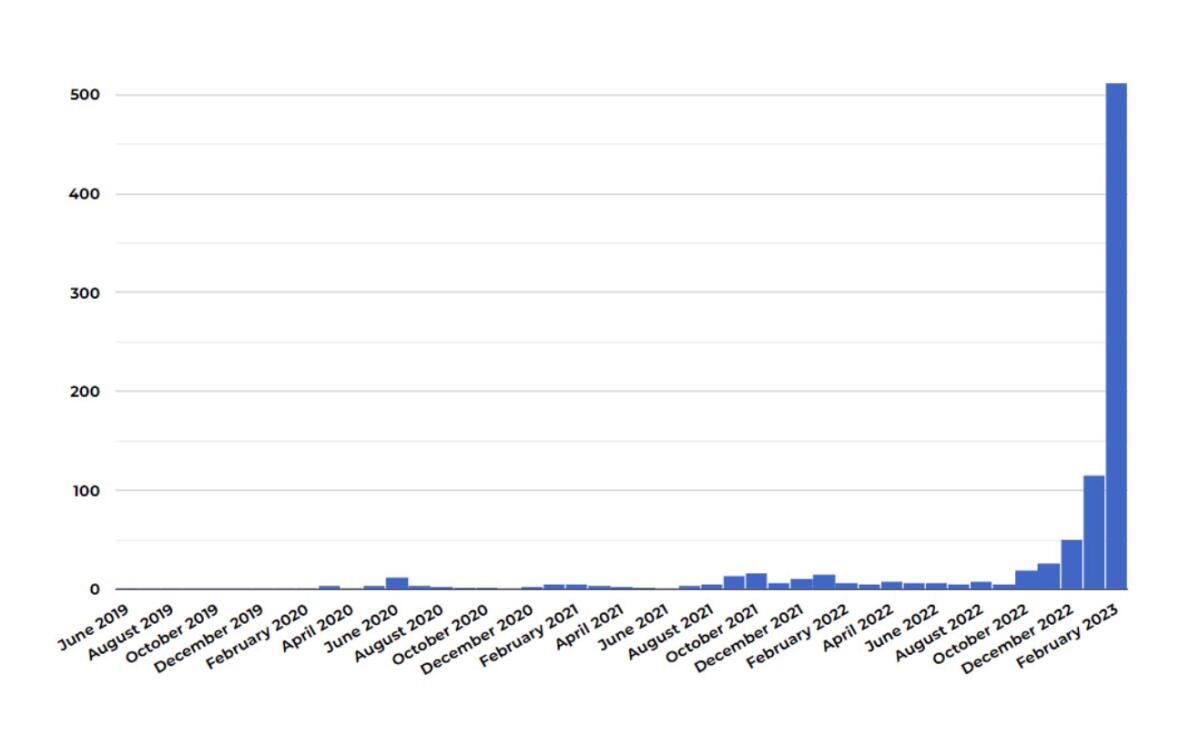

The problem ticked up during the pandemic’s lockdown phase, when workers confined at home were searching for ways to raise income. But it exploded in December, after San Francisco-based OpenAI publicly released its ChatGPT program, an especially sophisticated machine generator of prose.

Clarke reckons that of the 1,200 submissions he received this month, 500 were machine-written. He shut down submission acceptances until at least the end of the month, but he’s confident that if he hadn’t done so, the artificial pile would have reached parity with legitimate submissions by then — “and more than likely pass it,” he says.

This whole craze has taken over the world, and everyone’s in a frenzy.

— H. Holden Thorp, Science editor-in-chief

“We saw no reason to believe it was slowing,” says Clarke, 56. As he has done with plagiarists, he rejected the machine-generated content and permanently banned the submitters.

A veteran of the software industry, Clarke has developed rules of thumb that enable him to identify machine-written prose; he doesn’t share them, out of concern that simple tweaks would allow users to circumvent his standards. “They’d still be bad stories and they’d still get rejected, but it would be 10 times harder for us.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Regulatory systems have scarcely begun to contemplate the legal implications of programs that can trawl the web for raw material, including the prospect of widespread copyright infringement and fakery in prose and art.

The appearance of authenticity “will make generative AI appealing for malicious use where the truth is less important than the message it advances, such as disinformation campaigns and online harassment,” writes Alex Engler of the Brookings Institution.

The onslaught of machine-written material has become topic A in the periodical industry, because ChatGPT and similar programs known as chatbots have been shown to be capable of producing prose that mimics human writing to a surprising degree.

“Everyone’s talking about this, and a lot of people are focused on what this is going to mean for scientific publishing,” says H. Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the Science family of journals. “This whole craze has taken over the world, and everyone’s in a frenzy.”

AI sounds great, but it has never lived up to its promise. Don’t fall for the baloney.

Science has imposed the strictest policy on content generated by artificial intelligence tools such as chatbots among technical publishers: It’s forbidden, period.

The publications’ ban includes “text generated from AI, machine learning, or similar algorithmic tools” as well as “accompanying figures, images, or graphics.” AI programs cannot be listed as an author. Science warns that it will treat a violation of this policy as “scientific misconduct.”

Thorp further explained in an editorial that using programs such as ChatGPT would violate Science’s fundamental tenet that its authors must certify that their submitted work is “original.” That’s “enough to signal that text written by ChatGPT is not acceptable,” he wrote: “It is, after all, plagiarized from ChatGPT.”

That goes further than the rules laid down by Nature, which sits at the summit of prestige scientific journals along with Science. The Nature journals specify that language-generating programs can’t be credited as an author on a research paper, as has been tried on some published papers: “Any attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work,” Nature explains, “and AI tools cannot take such responsibility.”

But Nature allows researchers to use such tools in preparing their papers, as long as they “document this use in the methods or acknowledgements sections” or elsewhere in the text.

Thorp told me that Science chose to take a firmer stance to avoid repeating the difficulties that arose from the advent of Photoshop, which enables manipulation of images, in the 1990s.

“At the beginning, people did a lot of stuff with Photoshop on their images that we now think of as unacceptable,” he says. “When it first came along, we didn’t have a lot of rules about that, but now people like to go back to old papers and say, ‘Look what they did with Photoshop,’ We don’t want to repeat that.”

The Science journals will wait until the scientific community coalesces around standards for the acceptable use of AI programs before reconsidering their rules, Thorp says: “We’re starting out with a pretty strict set of rules. It’s a lot easier to loosen your guidelines later than to tighten them.”

Underlying the concerns about ChatGPT and its AI cousins, however, are what may be exaggerated impressions about how good they really are at replicating human thought.

What has been consistently overlooked, due in part to the power of hype, is how bad they are at intellectual processes that humans execute naturally and, generally, almost flawlessly.

Credulous media narratives about the “brilliance” of ChatGPT focus on these successes “without a serious look at the scope of the errors,” observe computer scientists Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis.

Helpfully, they’ve compiled a database of hundreds of sometimes risible flops by ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Bing and other language-generating programs: for example, their inability to perform simple arithmetic, to count to five, to understand the order of events in a narrative or to fathom that a person can have two parents — not to mention their tendency to fill gaps in their knowledge with fabrications.

One of our most accomplished experts in robots and AI explains why we expect too much from technology. He’s fighting the hype, one successful prediction at a time.

The heralds of AI assert that these shortcomings will eventually be solved, but when or even if that will happen is uncertain, given that the processes of human reasoning themselves are not well understood.

The glorification of ChatGPT’s supposed skills overlooks that the program and other chatbots essentially scrape the internet for existing content — blogs, social media, digitized old books, personal diatribes by ignoramuses and learned disquisitions by sages — and use algorithms to string together what they find in a way that mimics, but isn’t, sentience.

Human-generated content is their raw material, human designers “train” them where to find the content to respond to a query, human-written algorithms are their instruction set.

The result resembles a conjuror’s trick. The chatbots appear to be human because every line of output is a reflection of human input.

The astonishment that humans experience at the apparent sentience of chatbots isn’t a new phenomenon. It evokes what Joseph Weizenbaum, the inventor of Eliza, a 1960s-era natural language program that could replicate the responses of a psychotherapist to the plaints of a “patient,” noticed in the emotional reactions of users interacting with the program.

“What I had not realized,” he wrote later, “is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

It’s true that ChatGPT is good enough at mimicry to fool even educated professionals at first glance. According to a team of researchers at the University of Chicago and Northwestern, four professional medical reviewers were able to correctly pick out 68% of ChatGPT-generated abstracts of published scientific papers from a pile of 25 genuine and chat-generated abstracts. (They also incorrectly identified 14% of genuine abstracts as machine-written.)

Nature reports that “ChatGPT can write presentable student essays, summarize research papers, answer questions well enough to pass medical exams and generate helpful computer code.”

But these are all fairly generic categories of writing, typically infused with rote language. “AI is not creative, but iterative,” says John Scalzi, the author of dozens of science fiction books and short stories who objected to the use by his publisher, Tor Books, of machine-generated art for the cover of a fellow author’s latest novel.

(Tor said in a published statement that it had not been aware that the cover art “may have been created by AI,” but said due to production schedules it had no choice but to move ahead with the cover once it learned about the source. The publishing house did say that it has “championed creators in the SFF [that is, science fiction and fantasy] community since our founding and will continue to do so.”)

The tech site CNET brought in an artificial intelligence bot to write financial articles, but the product turned out to be worthless and even unethical.

Of the prospect that machine-generated content will continue to improve, “I think it’s inevitable that it will reach a level of ‘good enough,’” Scalzi says. “I don’t think AI is going to create an enduring work of art akin to a ‘Blood Meridian’ or ‘How Stella Got Her Groove Back,’” he said, referring to novels by Cormac McCarthy and Terry McMillan, respectively.

At this moment, the undisclosed or poorly disclosed use of chatbots has been treated as a professional offense almost comparable to plagiarism. Two deans at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education and Human Development have been suspended after the school issued an email in response to the Feb. 13 shootings at Michigan State University calling on the Vanderbilt community to “come together” in “creating a safe and inclusive environment” on campus.

The email bore a small-print notice that it was a “paraphrase” from ChatGPT. The Michigan shooter killed three students and injured five.

To be fair, Vanderbilt’s ChatGPT email wasn’t all that distinguishable from what humans on the university’s staff might have produced themselves, an example of “thoughts and prayers” condolences following a public tragedy, which seem vacuous and robotic even when produced by creatures of flesh and blood.

Chatbot products have yet to penetrate elite echelons of creative writing or art. Clarke says that what’s driving the submission of machine-written stories to his magazine doesn’t seem to be aspirations to creative achievement but the quest for a quick buck.

“A lot are coming from ‘side hustle’ websites on the internet,” he says. “They’re misguided by people hawking these moneymaking schemes.”

Others fear that the ease of generating authentic-seeming but machine-generated prose and images will make the technology a tool for wrongdoing, much as cryptocurrencies have found their most reliable use cases in fraud and ransomware attacks.

That’s because these programs are not moral entities but instruments responsive to their users’ impulses and reliant on the source material they’re directed toward. Microsoft had to tweak its new ChatGPT-powered Bing search engine, for instance, when it responded weirdly, unnervingly, even insultingly to some users’ queries.

ChatGPT’s output is theoretically constrained by ethical “guardrails” devised by its developers, but easily evaded — “nothing more than lipstick on an amoral pig,” Marcus has observed.

“We now have the world’s most used chatbot,...glorified by the media, and yet with ethical guardrails that only sorta kinda work,” he adds. “There is little if any government regulation in place to do much about this. The possibilities are now endless for propaganda, troll farms, and rings of fake websites that degrade trust across the internet. It’s a disaster in the making.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Guitar heatmap AI image. I, _Sandra Glading_, am the copyright owner of the images/video/content that I am providing to you, Los Angeles Times Communications LLC, or I have permission from the copyright owner, _[not copyrighted - it's an AI-generated image]_, of the images/video/content to provide them to you, for publication in distribution platforms and channels affiliated with you. I grant you permission to use any and all images/video/content of __the musician heatmap___ for _Jon Healey_'s article/video/content on __the Yahoo News / McAfee partnership_. Please provide photo credit to __"courtesy of McAfee"___.](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/f4350ab/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1600x1070+0+65/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F60%2Fef%2F08cda72f447d9f64b22a287fa49c%2Fla-me-guitar-heatmap-ai-image.jpg)