Proposition 30 has voters deciding on a tax for zero-emission vehicles. What you need to know

On its face, Proposition 30 is simple enough: Raise taxes on the richest Californians. Pull in $30 billion to $90 billion over the next 20 years. Use 80% of the money to subsidize electric vehicles and charging stations, and 20% for wildfire suppression and prevention.

The fight for votes has prompted plenty of sloganeering and a gusher of spending.

Supporters say Proposition 30 is essential to address climate change. Opponents say it’s not.

Opponents say higher taxes will chase wealthy, job-producing people from the state. Supporters say the rich can afford it, and there’s no proof high-income earners are fleeing the state.

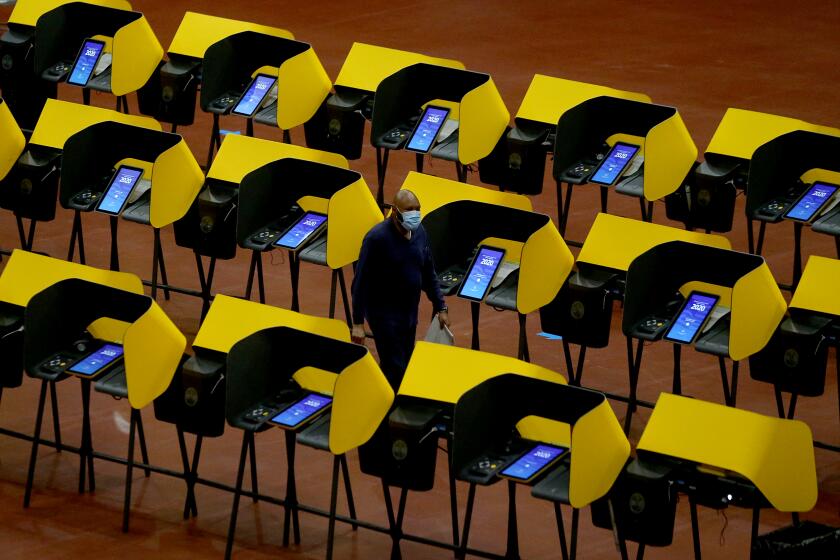

California’s November election will feature seven statewide ballot measures.

But nothing in California politics is simple, and Proposition 30 has sparked furious debate and heavy campaigning funded with more than $60 million in political donations. Most is being spent on mailers, TV commercials and social media campaigns that tend to wrap the issue in slogans and emotion.

Not sure how to vote on the issue and want to learn more about what’s at stake? Here’s what you should know:

Aren’t electric vehicles and charging stations heavily subsidized already?

Yes. The California Air Resources Board says the state has spent $6.5 billion thus far on emissions reduction programs for cars, trucks and other forms of transportation. The state’s new budget adds $10 billion over the next five years. Those figures don’t include federal subsidies for electric vehicles, also known as EVs.

Why would more money be needed?

Supporters say rampant wildfires are an early warning of greater disaster to come if climate issues are not addressed. Because transportation accounts for 40% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, it’s essential to switch as fast as possible to electric vehicles and to meet new California rules intended to phase out sales of new gasoline- and diesel-powered cars and light trucks by 2035. More money will help, they contend.

Furthermore, revenue from the state’s cap-and-trade carbon credit market, a major funder of emissions reduction programs, has proved erratic and unpredictable. California’s cap-and-trade program requires companies to buy permits to release greenhouse gas emissions and created a market for trading pollution credits, which essentially lets large carbon emitters buy and sell unused credits with the aim of keeping everyone at or below a certain total.

Electric vehicle buyers also sometimes have to wait months for rebates. Proposition 30 would reduce the uncertainty, supporters say.

Opponents of Proposition 30 say the $16.5 billion in past and future spending should be enough.

California’s electric car rebate program is designed to steer consumers toward clean, environmentally friendly vehicles. Unfortunately for buyers, it’s confusing, unpredictable and underfunded.

Couldn’t the Legislature fix the carbon credit issue on its own?

Yes. But that’s true for many propositions that make their way to voters. The Legislature did renew the cap-and-trade system with some reforms, but could do more to strengthen the program and smooth out funding, according to climate economist Danny Cullenward.

Cullenward, who takes no position on Proposition 30, said fears of revenue shortfalls from the cap-and-trade program later in the decade are “entirely credible.” He said state policymakers “could take significant steps to minimize these risks, but I do not see any signs that any such steps are being seriously considered.”

Proposition 30 critics note that the state’s tax system is notoriously erratic too, depending heavily on capital gains income that rises and falls with the stock market and the general economy. The highest earners provide a lopsided portion of the state’s personal income tax revenue, so when they do well, the state does well. When their investments tank, so does the state’s revenue.

Aren’t new electric vehicles a luxury that people without disposable income cannot afford?

The measure requires 50% of funding go to lower-income car buyers and to charging stations in lower-income neighborhoods.

So who would pay?

California residents with annual income over $2 million would see their top marginal state income tax rate rise by 1.75 percentage points, from 13.3% to 15.05%, on their income above $2 million. The tax increase would disappear by January 2043, or earlier if California is able to significantly drop its statewide greenhouse gas emissions.

Who are the measure’s biggest supporters?

Climate activists, climate-concerned politicians, the California Democratic Party and the ride-hailing company Lyft.

Lyft?

Under a state law passed last year, 90% of miles logged by Uber and Lyft drivers in California must be in electric vehicles by 2030.

Today the vast majority of ride-hailing cars are owned or leased by individuals who contract with Lyft and Uber. Lyft, which helped write Proposition 30 and has contributed $45 million to the “yes” campaign, wants state help to meet that mandate — more state money to encourage Lyft drivers to buy EVs and to fund a larger network of public chargers.

Uber, which has kept a low profile on Proposition 30, told The Times via email the company “was not involved in the drafting of Prop. 30, and we have no association with the campaign.”

Several labor unions are active as well — for and against. The International Brotherhood of Electric Workers likes the fact that Proposition 30 would probably create thousands of jobs for electricians. But the California Federation of Teachers and the California Teachers Assn. have come out strong against the measure.

Why teachers?

The proposition sets up a trust fund for the money and bars the Legislature from touching it. But because it’s not part of the state’s general fund, teachers see it as a way to work around the state constitutional mandate that a certain portion of new general fund spending go to schools. They worry that c more such carve-outs will be created to get around the requirements for education funding.

Who else is against it?

Rich people. The California Republican Party. Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Newsom is bucking his own party to fight the measure. He calls it “fiscally irresponsible” and “a Trojan horse that puts corporate welfare over the fiscal welfare of our entire state.”

Those lining up to donate money to shoot the measure down include venture capitalists Bruce Dunlevie, Michael Moritz and David Marquardt, former Well Fargo Chief Executive Richard Kovacevich, and former Oakland Athletics owner Lewis Wolff. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings recently gave the “No on 30” campaign $1 million.

What’s wrong with taxing the rich?

Nothing, according to supporters such as Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland): “Our high-income earners, frankly, they can afford these things.”

The danger, opponents say, is that raising what’s already the highest top marginal tax rate in the country will reflect negatively on California’s business environment and could chase wealthy people to other states.

Much research has been done on migration in and out of California. Most show that it’s lower-income people who tend to be moving out of the state. As for rich people fleeing California in a big way, “I don’t think that’s happening yet,” said California budget expert Patrick Murphy of the Opportunity Institute. But amid great economic uncertainty and another tax hike, “we might be nearing that point.”

An analysis of the ballot measure by the Legislative Analyst’s Office concluded that “some taxpayers probably would take steps to reduce the amount of income taxes they owe,” which could reduce state tax revenue overall and affect programs outside Proposition 30.

“The degree to which this would happen and how much the state might lose as a result is unknown,” the analysis stated.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.