Column: Trump’s judges will keep moving the country to the far right for decades

Ryan D. Nelson is a model of a modern anti-regulation conservative and culture warrior. As a Justice Department lawyer under President George W. Bush, he oversaw that administration’s campaign to go easy on polluters and roll back environmental rules.

In a 2007 case, he argued that tuna should be labeled “dolphin-safe” even if caught in nets known to cause millions of dolphin deaths. In private practice, he filed a brief for seven states arguing that governments shouldn’t be forced to upgrade their buildings in conformance with the Americans With Disabilities Act if the changes would cost money. His argument in the first case was rejected by an appellate court, and in the second by the Supreme Court.

The court is out of step with the American people...The majority of Americans want Roe upheld, but the court might well go the other way. A majority of Americans would like to see some regulation of guns; the court may not do that.

— Former U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin

Nelson’s waffling about the human contribution to global warming at a Senate hearing on his nomination by President Trump to a top Interior Department post prompted Trump to withdraw his nomination in 2018.

Instead, Trump named him to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction over California and seven other Western states.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Republican Senate confirmed him, and he sits on that court today. In May, he was the author of a 2-1 majority opinion declaring unconstitutional California’s ban on the sale of semiautomatic weapons to those under 21.

The ruling, handed down on May 11, less than two weeks before an 18-year-old gunman used a similar weapon to slaughter 19 schoolchildren and two adults in Uvalde, Texas, evoked an America beleaguered by frontier lawlessness.

The California ban, he wrote, would leave young persons unable to protect themselves except with shotguns. As he wrote, “shotguns are outmatched by semiautomatic rifles .... Semiautomatic rifles are able to defeat modern body armor, have a much longer range than shotguns and are more effective in protecting roaming kids on large homesteads.”

Nelson, 48, is just one of a legion of youthful conservative judges appointed to lifetime terms by Trump in what may be the most far-reaching and radical remaking of the federal judiciary in American history.

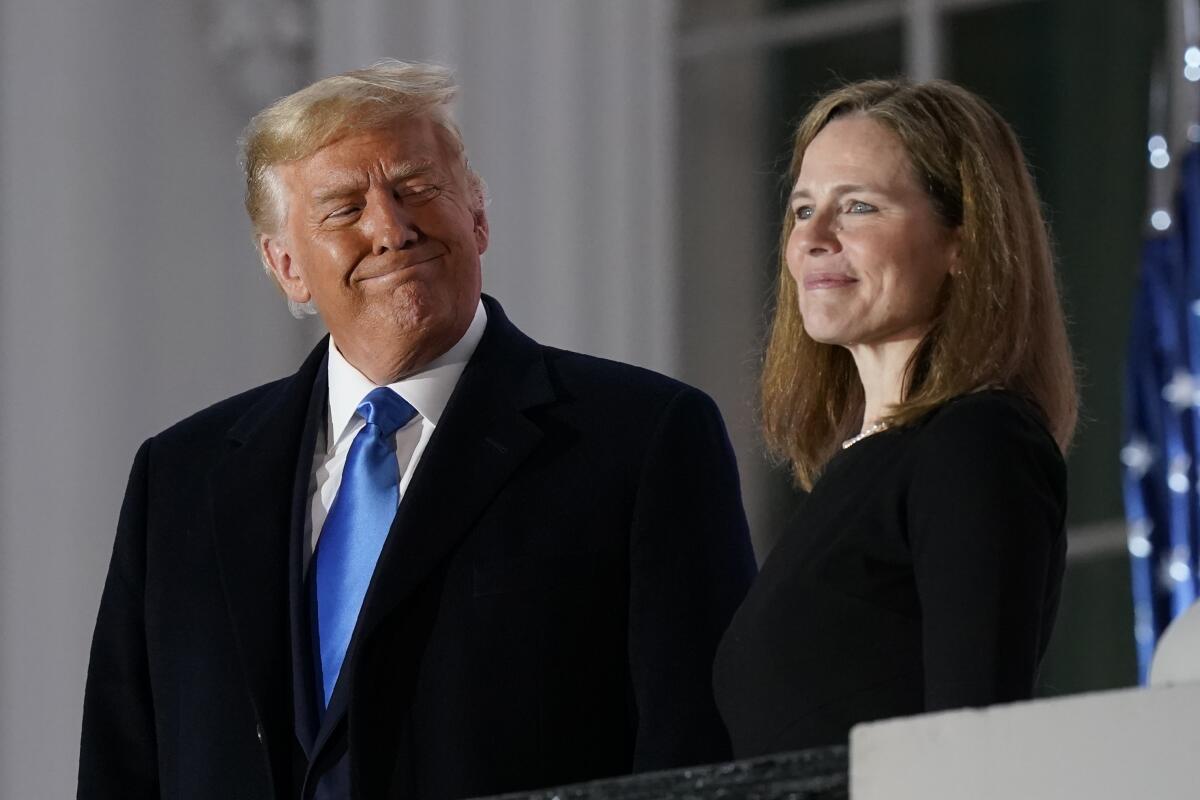

Trump was able in his sole term to fill 28% of the 816 federal judicial seats, including 30% of the appellate judgeships and three of the nine Supreme Court seats, giving the latter court a potent 6-3 conservative majority. In this effort he was abetted by a Republican Senate majority that refused to fill open seats under President Obama and hastened Trump’s appointees onto the bench.

The idea of imposing a term limit on Supreme Court justices is gaining traction.

The GOP’s blocking of Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court is the best-known example of Republican obstruction, but once it gained a Senate majority it slow-walked Obama’s nominations to the rest of the appellate bench, yielding a surfeit of vacancies for Trump to fill.

“Trump ran on changing the judiciary as a political point,” says Shira A. Scheindlin, a former federal judge in New York who is co-chair of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “He said, ‘I will appoint judges who will overturn [Roe vs. Wade]. I will appoint judges who will protect your guns.’ He said all along this was a political issue for him, and he did move at lightning speed.”

Indeed, despite opinion polls consistently showing that a strong majority of Americans want the Supreme Court to uphold Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 opinion guaranteeing abortion rights nationwide, the court appears poised to overturn the ruling, perhaps within days or weeks, in a case involving a draconian Mississippi antiabortion law.

A majority of Americans favor stricter gun safety regulations, but those are also threatened by a pending ruling on New York regulations.

Trump outsourced the naming and vetting of Supreme Court candidates to the Federalist Society, a conservative legal group founded during the Reagan presidency and funded by the Koch network, as legal reporter David A. Kaplan documented in his 2019 book about the Trump-era Supreme Court, “The Most Dangerous Branch.”

Trump’s goal was to move appellate courts, not only the Supreme Court, to the right. He succeeded in three circuits: the Philadelphia-based 3rd, flipped from a majority of Democratic appointees to Republicans; the New York-based 2nd, which also flipped from a Democratic to Republican majority; and the 9th, which covers California and eight other states and with 29 active judges is the largest appellate court in the country.

Biden has an opportunity to flip the 3rd Circuit back, though none of his appointees has yet been confirmed by the Senate. He has already flipped the 2nd, an important court that oversees a large share of business-related cases, back to a narrow Democratic majority.

Trump’s influence may be most notable at the 9th Circuit. At the end of the Obama administration, the court was split 18 to 7 in favor of Democratic appointees. Trump’s 10 appointments to the court reduced the Democratic majority to 16 to 13. Biden has appointed three new judges to the court, but all replaced Democratic appointees.

“Trump has effectively flipped the circuit,” 9th Circuit Judge Milan D. Smith Jr., an appointee of George W. Bush, told The Times in 2020.

The notion of expanding the Supreme Court has been gaining traction lately, thanks in part to the court’s distinct rightward tilt, its increasingly partisan character, and its apparent hostility to abortion rights.

Two of the new appointees rattled their colleagues with their obliviousness to traditional court decorum. One, Lawrence VanDyke, a former solicitor general in Nevada and Montana, earned an unusual “not qualified” rating from the American Bar Assn., which found him to be “arrogant, lazy, an ideologue, and lacking in knowledge of the day-to-day practice, including procedural rules.”

Trump’s appointments have produced a string of rulings promoting partisan political and ideological positions. Many of these affect “a whole slew of issues on which the vast majority of Americans are either much more centrist or liberal on than the court is,” says Jake Faleschini of the progressive advocacy group Alliance for Justice.

During the pandemic, Trump-appointed judges often overturned state and local regulations aimed at limiting potential super-spreader gatherings such as indoor religious services. They kept alive a lawsuit filed by Texas and other red states to declare the Affordable Care Act unconstitutional (an argument ultimately rejected by the Supreme Court).

Trump-appointed district and appeals judges have upheld numerous state restrictions on abortion rights, including defunding of women’s health clinics. That’s against the backdrop of a pending Supreme Court decision in which the three judges appointed by Trump are widely expected to be part of a conservative majority overturning Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 decision that guaranteed the right to abortion nationwide.

Trump judges have voted to narrow the access of prison inmates and business employees to healthcare and disability benefits. They have turned a blind eye to state regulations aimed at undermining voting rights and overturned anti-discrimination laws designed to protect LGBTQ rights.

When it comes to another front-burner issue — gun control — Trump judges have been all-in on expanding gun rights and overturning state and local firearm regulations. That’s a particular concern for California, which has enacted some of the strictest gun control laws in the nation, and has achieved one of the lowest rates of firearm deaths in the country as a result.

Republicans demand instant action to protect Supreme Court justices. Let’s tie that to an assault weapons ban.

As my colleague Anita Chabria has observed, federal judges, especially those appointed by Trump, may represent the gravest threat to the safety of California residents. Nelson’s ruling overturning the state’s ban on semiautomatic weapons was only one sign of a tsunami to come.

In 2020, writing for a 2-1 majority of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, Trump appointee Kenneth K. Lee overturned California’s ban on large-capacity magazines, or LCMs, holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition, as an infringement of the 2nd Amendment right to bear arms.

Like his colleague Nelson, Lee invoked “the right to defend hearth and home” against a putative phalanx of marauders.

“The ban makes it criminal for Californians to own magazines that come standard in Glocks, Berettas, and other handguns that are staples of self-defense,” Lee wrote. “Its scope is so sweeping that half of all magazines in America are now unlawful to own in California .... Many Californians may find solace in the security of a handgun equipped with an LCM: those who live in rural areas where the local sheriff may be miles away, law-abiding citizens trapped in high-crime areas ... and many more who rely on their firearms to protect themselves and their families.”

The likelihood that Trump’s stamp on the federal judiciary will persist doesn’t derive only from the sheer number of his appointees occupying the bench.

Trump also picked relatively young judges, whose judicial careers might last for three or four decades or more. The average age of Trump’s appointees to the appellate circuits was 47, five years younger than those selected by Obama, Scheindlin observed in an article last year.

“Six of those were in their 30s, and 20 were under 45,” Scheindlin wrote. “By contrast, of the 55 appellate judges picked by Obama — in eight years, not four — none were in their 30s and only six were younger than 45.”

Perhaps inevitably, Trump’s younger nominees came to the bench without significant judicial experience or even lawyerly seasoning. One example is Kathryn Kimball Mizelle, a federal judge in Orlando, who issued a widely ridiculed ruling striking down the federal mask mandate for airlines and other public transportation on April 18. The Biden administration is appealing the ruling.

Mizelle was appointed in 2020 at the age of 33 by Trump after he had already lost reelection, becoming one of the youngest appointees to the federal bench in history. She was confirmed on a party-line vote despite being deemed unqualified by the American Bar Assn., in part because, having graduated from law school in 2012, she did not have close to the 12 years’ legal experience the bar considered the bare minimum for a federal judge.

At the time of her nomination, Mizelle had participated in only two cases to the point of reaching a verdict — both as a legal intern, before she even had graduated from law school or obtained a law license.

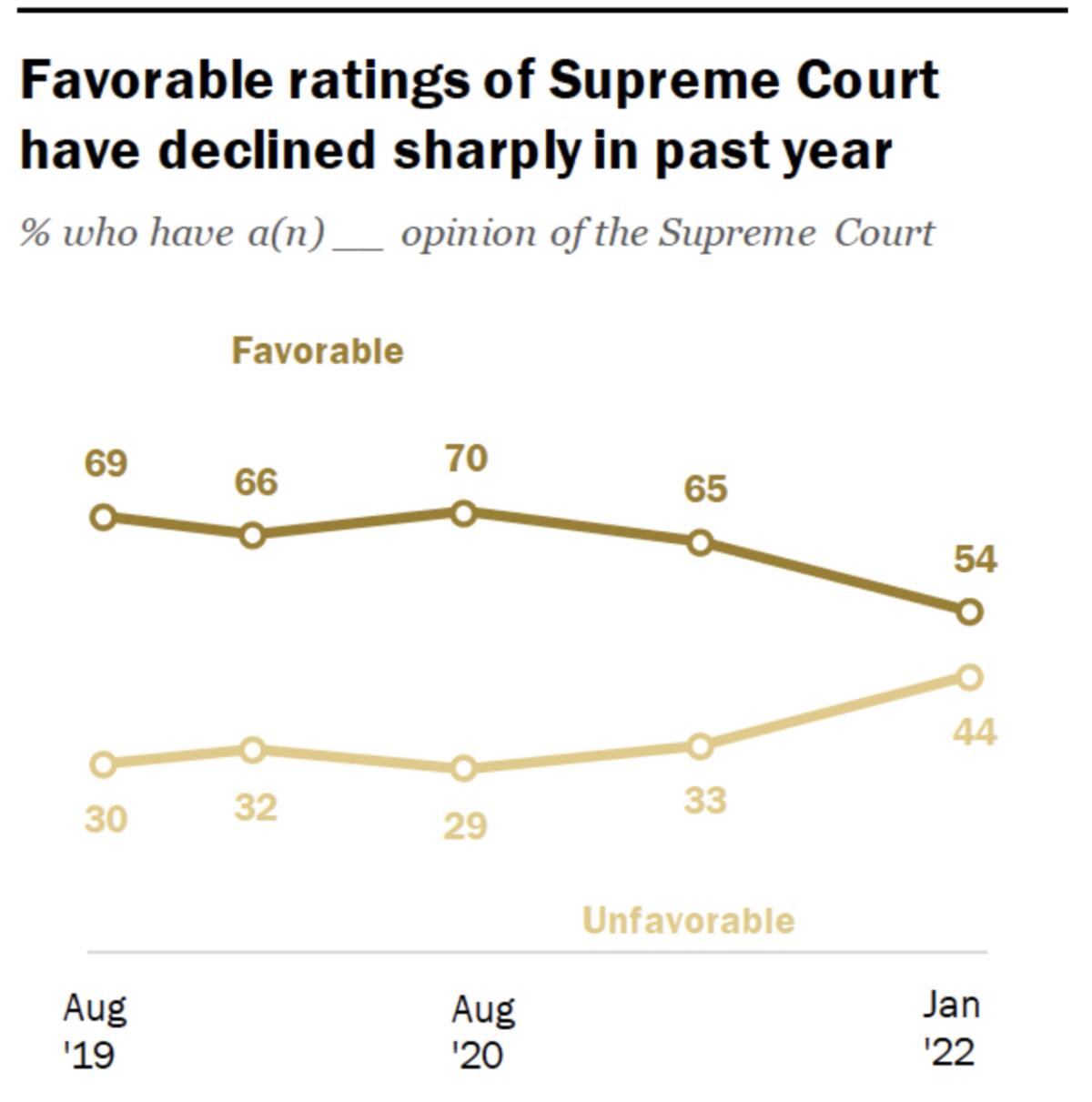

The extreme rightward shift of the Supreme Court has already begun to erode the court’s public standing.

The dark side of Earl Warren’s past is his advocacy of Japanese incarceration during World War II.

The Pew Research Center found in February that only 54% of respondents had a favorable view of the court, down from 69% in mid-2019, according to several opinion polls. “Current views of the court are among the least positive in surveys dating back nearly four decades,” the Pew pollsters reported.

Other poll results are even more dire — the Gallup Organization reported last year that Americans disapproved of the court’s performance by 53% to 40%.

“The court is out of step with the American people,” Scheindlin says. “The decisions we are seeing are not popular. The majority of Americans want Roe upheld, but the court might well go the other way. A majority of Americans would like to see some regulation of guns; the court may not do that.”

This isn’t the first time that the court moved so far apart from public opinion that its credibility was jeopardized.

In the 1930s, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes perceived a decline in the court’s public standing resembling today’s.

Seeking to curb the court’s open hostility to New Deal and other progressive initiatives that had given birth to Franklin Roosevelt’s 1937 court-packing scheme, Hughes orchestrated a reversal of the court’s previous invalidation of a state minimum wage law by persuading one justice to change his mind. The “switch in time that saved nine” helped to torpedo FDR’s plan.

It doesn’t appear, however, that Chief Justice John Roberts has the same influence over his colleagues that Hughes exercised. In part, that’s because the conservative majority is larger than in the 1930s and it’s composed of more obdurate ideologues.

It’s unclear what could shift the Supreme Court toward the center, other than persistent Democratic control of the White House and Senate and the passage of time. The American political and constitutional systems do not offer many options to change the ideological direction of a body endowed with lifetime appointments, other than expanding the size of the court or imposing term limits on justices.

Even under the most hospitable conditions, either option would probably take years to make a mark. (The size of the court is under the control of Congress; whether term limits would be constitutional is the subject of vigorous debate by legal experts.)

“Unless the House and Senate decide by the end of this year to do away with the filibuster and expand the Supreme Court by four justices, this isn’t going to change any time soon, outside of an act of God,” Faleschini says.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.