Column: Millions of Americans are fixated on stock prices. They shouldn’t pay such close attention

Following the Dow, are you?

The widely watched stock market indicator has been all over the place this month: two triple-digit gains and no fewer than 10 triple-digit declines out of the 17 trading days so far this year (including Wednesday, when the market rolled over after the Federal Reserve Board projected an interest rate hike as soon as March).

On Monday, the blue-chip index fell more than 1,100 points, or about 3.25%, from the previous close, only to end the day nearly 100 points higher.

“The federal government is the most important financial partner for most Americans.”

— Economist Teresa Ghilarducci

The broader stock market also has been in a swoon. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index has fallen by 7.5% this month, after gaining nearly 27% in 2021.

If you’re paying close enough attention to be alternately clutching your chair arms until your knuckles turn white and taking deep breaths of relief, you’re doing it wrong.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The ups and downs of the stock market, especially the widely cited Dow Jones industrial average, communicate an easily accessible narrative through which to grasp economic trends.

As the Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Shiller observed in his 2019 book “Narrative Economics,” these stories allow us to construct a coherent picture out of a welter of complex and confusing events and conditions.

The narrative built to explain the stock market boom of 2000, he wrote, brought together the advent of the World Wide Web, baby boomers entering retirement, the decline in inflation, and optimism about business — “seemingly unrelated narratives that all happened to be going viral at around the same time.” That narrative held only temporarily, however, because the bubble burst in 2001.

GameStop’s rocketing price defined the insane stock market of 2021. Now it’s plummeting.

The narrative fashioned around stock market indexes, Shiller wrote, persists in part because the daily changes are incessantly reported by the news media and because “people widely believe that the stock market is a fundamental indicator of the economy’s vitality.”

That’s often misleading, however. “Much more relevant is growth in GDP”—gross domestic product—”especially over the long term,” says Edward Wolff, a professor of economics at New York University.

More important, the stock market is irrelevant to most people’s financial situation. “For the middle class, wages are much more important than stock prices,” Wolff says.

For the vast majority of Americans, any fixation on the short-term ebb and flow of stock prices — especially daily price changes — may even be financially unhealthy.

There are several reasons why that’s so. To begin with, most Americans have little or no direct exposure to the stock market.

Only about 15% of all families own shares of stock directly, and even that figure is skewed by significant holdings by the top 10% of households (those with net worth of $1.2 million or more); about 44% of those households own stocks directly.

Among households with net worth around the national median of $121,700, only about 11% own shares of stock; among the poorest 20%, with net worth of $6,400 or less, only about 5% own stocks. (The figures are from the Federal Reserve’s latest triennial Survey of Consumer Finances, which was published in 2019.)

Overall, direct stock holdings have fallen from their high point of 21.3%, reached in 2001. Two market crashes drove American families out of love with the stock market, though holdings have recovered a bit from their low point of 13.8% in 2013.

About 53% of all households own stock in one form or another, but they do so mostly through retirement accounts.

Holdings in defined contribution plans such as 401(k)s tend to be in stock mutual funds, such as index funds — about two-thirds of the more than $7.3 trillion invested in 401(k) plans as of mid-2021, according to the Investment Company Institute. An additional 10% is placed in bond or money market mutual funds.

These are professionally managed, so they tend to be comparatively immune to the sort of emotional reactions that can prompt investors to make the wrong decisions at the wrong moments — panic-selling during downturns or overly exuberant buying during bull frenzies, for example. They’re also designed to build wealth over decades, capturing long-term economic trends instead of being buffeted by short-term swings.

Robinhood announced plans for an IPO one day after the company settled regulatory charges that should make the average customer or investor wonder.

Defined benefit pensions, through which workers are guaranteed payouts based on their wages and job longevity, provide even more of a buffer from stock market swings, since it’s the managers of the pension funds, not the workers, who shoulder the market risk.

Even within the top 10%, direct stock holdings represent a fairly small proportion of their assets. “Though 70% of the top 10% directly own stocks,” economist Teresa Ghilarducci of the New School told the Senate Banking Committee last year, “it is only 13% of their wealth.” Businesses they own, real estate and retirement accounts and pension plans account for more than half their net worth, on average.

Over the last year or two, the narrative of stock trading as a pathway to wealth has gained in prominence. As Ghilarducci asserts, that’s a distinctly unwholesome development, especially for younger people who may just now be entering their prime earning years.

A surge in interest in short-term stock trading has been spurred by zero-commission brokerages such as Robinhood, which plies young investors with the impression of stock trading as a fun game and the notion that stock trading needed to be “democratized” — that is, removed from the control of big Wall Street players and placed in the hands of the retail trader.

“Robinhood has pushed financial literacy in reverse rather than advancing it,” Ghilarducci told me. “Places like Robinhood are making lots of money out of promoting this ideology of ‘democratization.’ They’re really hitting people who are used to electronic games, like young men. That’s distorting the decisions of some people, putting them at great risk.”

Robinhood is not only making a game of stock trading but also luring customers into riskier investments such as options and nonsensical investments such as cryptocurrencies.

“We have to regulate these financial predators who traffic in the idea that wealth-building will happen if people have access to these risky products and services,” Ghilarducci says.

She’s right. The truth is that for a majority of Americans, the principal source of wealth isn’t savings accounts, private retirement plans, stocks and bonds, or home equity. It’s Social Security.

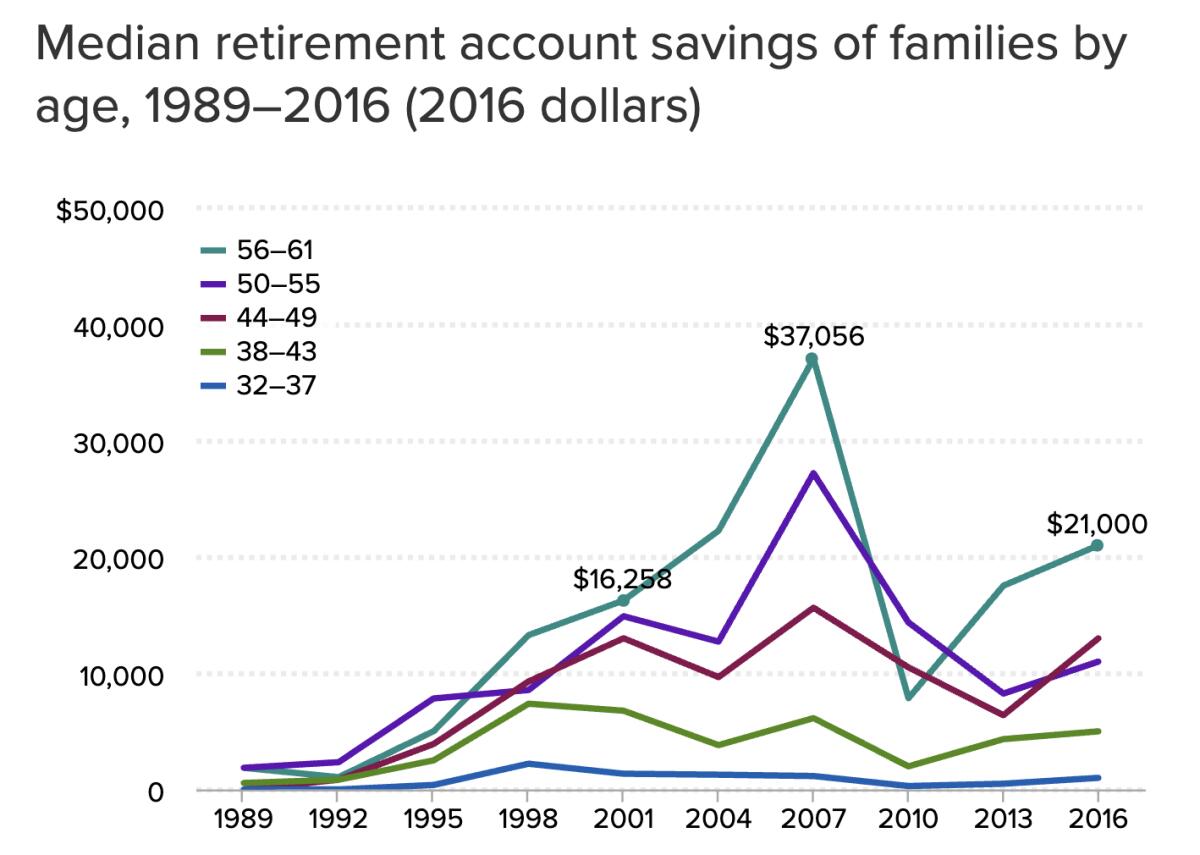

For households with a member over 52, the program’s median contribution to the retirement nest egg — that is, the present value of expected payouts for those who claim benefits at full retirement age — is larger than that of any other source except among the richest 10%, according to Ghilarducci’s calculations.

For them, Social Security’s median contribution of $274,966 is exceeded by home equity (median value of $400,000) and private retirement plans (median holdings of $823,000).

Has any era given birth to more dubious investment mechanisms than today?

In 2015, the latest calculations available, Social Security accounted for more than half the income of 37.3% and more than nine-tenths of the income for 12.1% of men over 65. The program provided more than half the income for 42% and more than nine-tenths of the income for about 15% of women over 65.

That underscores the imperative of protecting Social Security from efforts at tampering, such as President George W. Bush’s plan to privatize the system, and proposals to cut benefits. “Across-the-board cutbacks in benefits,” MIT economist James Poterba wrote last year, “would place heavy burdens on the subset of beneficiaries who are highly reliant on this program for retirement support.”

Fascination with stock-picking may stem partially from doubts that Social Security will exist long enough to safeguard Americans’ retirements decades from now. Another factor is the recognition that the private pension structure of the past, through which employers rewarded workers for their long-term loyalty, has collapsed; fewer than 1 in 5 American workers have access to those pension plans.

That system has been supplanted by 401(k)-style defined contribution plans, which place the responsibility for funding, as well as the risks of market reversals, on the workers themselves.

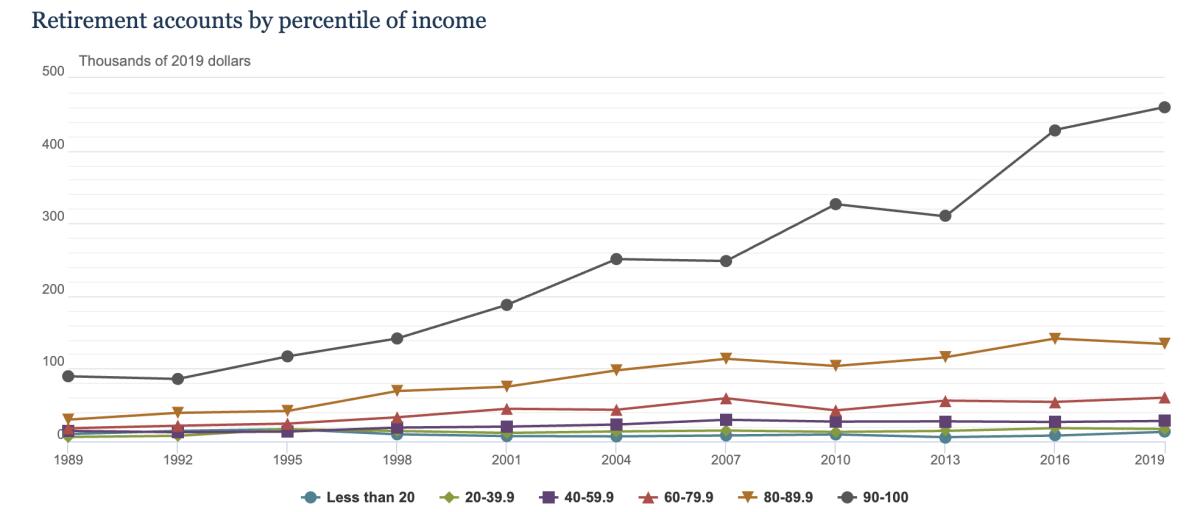

Defined contribution plans, however, favor higher-wage employees far more than did the old-style defined-benefit pensions. Some 44% of all households participate in a defined contribution plan sponsored by an employer, but participation ranges from only 10% among the lowest-wage 20% of families to 70% among the top fifth.

That could reflect the difficulty that lower-wage families have in setting aside contributions for their retirement, as well as the greater tax savings that richer workers obtain by placing some of their income in the tax-advantaged plans.

The emergence of weird get-rich-quick come-ons such as cryptocurrencies and nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, distracts from the fact that “the federal government is the most important financial partner for most Americans,” Ghilarducci says.

That’s true. Social Security is an indispensable bulwark against poverty for its 65.2 million beneficiaries; Medicare covers medical expenses for 61 million enrollees, mostly age 65 or older; and Medicaid provides medical coverage for 82 million lower-income Americans, including children. The stock market has no impact on any of these programs.

Americans who want to devote mindshare to how to build and protect their wealth for the long term should spend it on making sure that our political leaders focus on making them stronger.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.