Column: There’s a right way and a wrong way to think about inflation. Here’s a right way

Is there an economic term that strikes more fear into the hearts of consumers than “inflation”?

Probably not. When inflation is rising even modestly, it becomes Topic A in the press, on cable news and over the proverbial backyard hedges and dinner tables.

Inflation is commonly regarded as a ravager of family budgets, a destroyer of political fortunes and, at its most extreme, a trigger for the rise of fascism.

Inflation can be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

— Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen

The result, investor and economic commentator Zachary Karabell writes, is that “any hint of inflation triggers the equivalent of PTSD in the ranks of central banks, economists, policymakers and millions of middle-class wage earners.”

Yet that was not always so — indeed, it’s not invariably so even today.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

At the moment, we’re experiencing more than a mere hint of inflation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that prices in October rose 6.2% over a year earlier, the largest 12-month increase in more than 30 years, or since November 1990. Core inflation — absent food and energy — rose 4.6% over the last 12 months, the largest such increase since August 1991.

But inflation is an inherently complicated subject — its causes are tangled, its effects variable. Consequently, it lends itself to confusion and misunderstanding.

More to the point, consumer psychology may play an outsized role in fomenting inflation, for consumer behavior inspired by inflation fears contributes to the phenomenon by prompting more spending or less spending, as the case may be.

As I reported recently, Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen warned in an interview with NPR that “inflation can be a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The latest inflation numbers shocked even pessimistic economists, but they’re still transitory.

Not every consumer is affected by inflation in the same way; for some it’s even a blessing. It depends on what people treat as crucial purchases for the near term, on what they can defer or forgo entirely, and on the source of their income. If your wages are rising faster than the cost of your market basket, you may even regard inflation as your friend.

The roots of inflation fear are embedded memories of hyperinflationary periods of the past. The German hyperinflation of the 1920s contributed to the rise of Hitler and ingrained a horror of inflation in German economic policy — and therefore European economic policy — ever since.

More recently, there was the oil price-driven inflation of the 1970s and the “stagflation” period in the U.S., in which high unemployment and high inflation went confoundingly hand in hand.

The inflation of that era was quelled only after then-Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker orchestrated a recession and allowed interest rates to rise as much as was necessary to reduce the money supply.

Volcker’s medicine was harsh — mortgage rates exceeded 18%, investors abandoned the stock market for money market funds (on Aug. 13, 1979, the cover story in BusinessWeek carried the now-legendary headline “The Death of Equities”) and Jimmy Carter lost the 1980 presidential election to Ronald Reagan.

But it worked. The annual inflation rate fell from 13.3% in 1979 to 1.1% in 1986, and the stock market, far from being moribund, embarked on an unprecedented series of bull runs.

With those recollections so relatively fresh, it’s often forgotten that there have been periods in American history when political pressure was on the other side of the ledger — in favor of increasing inflation.

Typically the impetus began in the farm belt, which often suffered from falling crop prices, especially when prices of agricultural land and equipment were rising and farmers could get no relief from crushing debt.

That was the underlying inspiration for William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 Democratic convention. Its target was the gold standard, which preserved the wealth of the bondholding class and represented an economic knee on the necks of farmers.

During the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt sought desperately for means to inject inflation — not too much, but just enough — into the economy to pull farmers out of a depression that had afflicted them virtually since the end of World War I.

Members of Roosevelt’s brain trust were certain that Herbert Hoover’s obsessive anti-inflation stance, especially his staunch defense of the gold standard, had exacerbated the economic slump in the U.S., especially after Britain and other European states abandoned gold.

FDR ignored Hoover’s insistence during the long interregnum between the 1932 election and Roosevelt’s inauguration on March 4, 1933, that he commit himself to a “sound money” non-inflationary policy.

Instead, about six weeks after the inauguration, Roosevelt took the U.S. off the gold standard. This was the first signal that Roosevelt intended to fuel the U.S. recovery by controlled inflation to relieve pressure on farmers, businesses and homeowners, whose debts became cheaper to pay off as prices rose.

The anti-deficit crowd is wrong about deficit spending. Don’t let them kill the Build Back Better plan.

FDR’s approach reflected an implicit understanding that some inflation is benign, even desirable. That’s because it stems from economic growth and improving productivity. It also provides a cushion against deflation, a destructive phenomenon because it prompts consumers to hoard money and delay purchases in anticipation of lower prices, thus aggravating economic downturns.

The optimal inflation rate has been an enduring topic of debate among policymakers. From 2000 through the 2009 recession, the Federal Reserve’s target was 1.5%; since then it has been 2%.

Conventional wisdom holds that sustained annual inflation of 3% or higher can drive prices out of the reach of many consumers, and rates above 10% create political, economic and social instability, as happened as a result of the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Economists place the causes of inflation into three main categories.

“Demand-pull” inflation comes from consumer spending in a growing economy, reflecting healthy consumer confidence and a willingness to borrow to finance consumption. “Cost-push” inflation comes from shortages of raw materials, labor and merchandise that aren’t available or aren’t produced enough to meet demand.

Finally, there is the expansion of the money supply — overexpansion, that is — resulting in more money sloshing around in the economy than can reasonably be spent on goods and services.

These causes all affect wages. Traditionally, wages have risen at a rate of about 1% higher than the consumer price index, reflecting economic improvement. When wages rise faster than that, businesses will complain about labor costs; when they fall behind, workers will feel trapped in an economy that fails them.

Today’s inflation environment bears all these features in one sense or another. Consumers have emerged from the long pandemic lockdowns in a mood to spend and travel; oil-producing countries have refused to increase output to meet resurgent demand, resulting in a sharp rise in the price of oil.

The port logjam and production slowdowns in computer microprocessors have contributed to merchandise shortages, driving up prices of cars and appliances. Federal pandemic relief programs, including augmented unemployment benefits, put money in household budgets. Workers’ resistance to returning to lousy jobs has forced employers to raise wages.

The first factor is likely to fade in coming months and the second has already run its course. The third may persist, but of course wage increases will moderate or even overcome the impact of price increases on household budgets. Altogether, those factors suggest that the current inflation rate will fall, perhaps almost as sharply as it rose, through the beginning of next year.

That may explain why consumers’ and investors’ responses are essentially incoherent. The latest consumer confidence survey of the University of Michigan reached its lowest point in a decade this month, largely because of the recent surge in inflation.

Yet air travel is expected to exceed last year’s pandemic-suppressed level by 80% and Christmas spending will come close to the last pre-pandemic holiday season, 2019. On Wednesday, the Commerce Department reported that personal spending increased 1.3% in October, an unexpectedly large gain and the most since a 4.2% increase in March.

The report prompted JPMorgan Chase & Co. to revise its estimate of fourth-quarter economic growth to an annualized 7%, up from 5%, and Morgan Stanley to raise its projection to 8.7% from 3%.

So far, investors haven’t shown that they’re fazed by the inflation surge. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index, a measure of the overall stock market, is up by nearly 23% this year. Inflation expectations among bond investors, for whom inflation is an all-encompassing nemesis, have barely budged from an average projected rate of just over 2% for the next five years, even as short-term inflation has exploded.

As is almost always the case, the impact of inflation on families and individuals can depend not only on the price of necessary goods and services but on the choices people make for themselves.

The new child tax credit being paid out to American parents will prove the virtues of universal basic income.

As my colleagues Russ Mitchell and Brian Contreras report, high gas prices have hit the owners of modern muscle-bound pickup trucks hard — filling a 26-gallon gas tank even with regular at the average California price of $4.70 will cost more than $120. For the owner of a Ram 1500 pickup getting as little as 15 miles a gallon, unloaded, that runs into money.

Yet for many owners, a heavy-duty pickup is more a fashion statement than a necessity; owner surveys indicate that more than 70% use their vehicles for towing or going off road once a year or less, and only 35% ever put anything in the truck bed for hauling.

Some of the price increases that have worked their way into recent monthly inflation statistics may be less important to average families than they may seem at first glance. New- and used-car prices rose over the last 12 months by 1.4% and 2.5% respectively, but the average family doesn’t experience sticker shock in the car market very often; households hang on to their cars and vans for longer than 10 years on average.

Other prices are plainly transitory. Lumber spiked earlier this year, provoking hand-wringing about the rising cost of residential construction. But prices peaked at $1,670.50 per 1,000 board-feet in May and have since fallen by more than half to below $773. That’s still about twice the price in October 2019, but not four times the price, as it was at the peak.

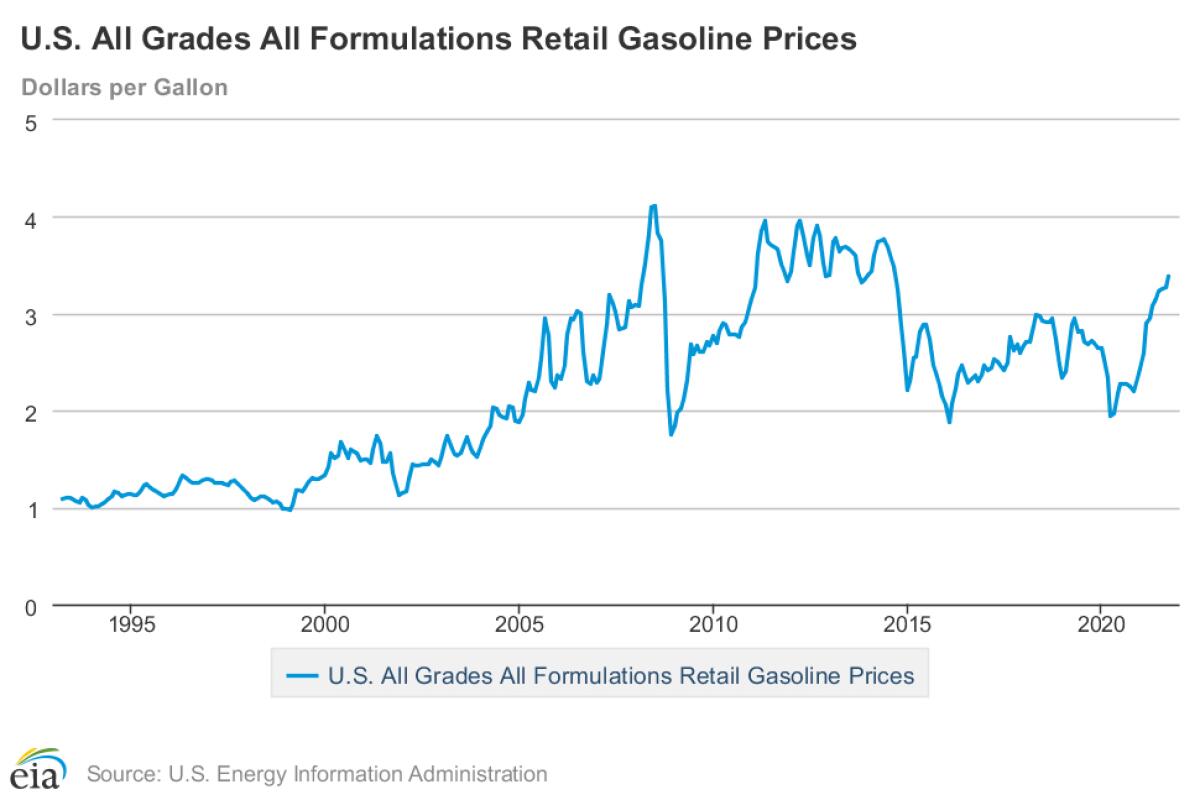

Gasoline prices today are actually lower than they were at their peak in the summer of 2008 — currently averaging $3.40 nationally, according to the Automobile Club of America, compared with an inflation-adjusted $5.23 in mid-2008.

Economists have long understood that consumers are adept at moderating the effects of inflation through “substitution” — when apples become expensive, they buy oranges, when beef prices rise, they move to cheaper cuts, and so on. Over the last year, beef has risen by as much as 25%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but pork by 14.1%, whole chicken by 6.8% and frozen fish by 4.6%.

It’s not unreasonable to conjecture that some families have shifted their protein choices in response. That doesn’t mean they’re not feeling the bite of higher prices, but they may be exploring their options. (Turkey was costlier this Thanksgiving by only 1.7% compared with last year.)

It’s true, of course, that many families can’t escape higher prices on necessities. Natural gas for household heating and cooking, for example, is up by nearly 30% over the last year.

So where do we go from here? Inflation fears have the capacity to affect policy in self-destructive ways by discouraging government investments with long-term anti-inflationary effects, such as improving the nation’s physical and human infrastructure through construction and assistance with child care and education costs.

If Republicans and conservative Democrats were really concerned about the impact of higher prices on ordinary Americans, they would vote to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour instead of keeping it at $7.25, where it has been mired for more than 12 years during which consumer prices have risen a cumulative 28%. They would vote to make the child tax credit permanent, instead of settling for a single year’s extension. And they would vote to provide for paid family and medical leave for 12 weeks, instead of zero weeks.

That may be the most important danger posed by the current atmosphere of PTSD, as Karabell put it.

There are no signs that the inflation surge showing up in the latest statistics is caused by sustained overheating of the U.S. economy. The signs point to several short-term factors coming together all at once — trade logjams, a surge in post-pandemic demand for goods, limited step-ups in oil production, labor demands for a living wage.

Economist Stephanie Kelton calls the economic gains resulting from the miraculous development of COVID-19 vaccines and generous pandemic relief spending “good problems to have.” Allowing near-term inflation fears to undermine longer-term investments would be penny-wise and just plain foolish.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.