Column: Gov. Abbott says Texas can solve California’s port logjam. As usual, he’s blowing smoke

One thing you can say about Texas Gov. Greg Abbott is that he’s never afraid of looking like a jackass when defending his own retrograde social policies or trying to pump up his state’s reputation as a friendly place to do business.

Abbott’s latest flight of fantasy concerns the backlog at America’s ports, especially the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

For the record:

8:23 a.m. Nov. 6, 2021An earlier version of this column reported that Elon Musk had announced he was moving Tesla’s headquarters to Houston. Musk said the headquarters would be moved to Austin.

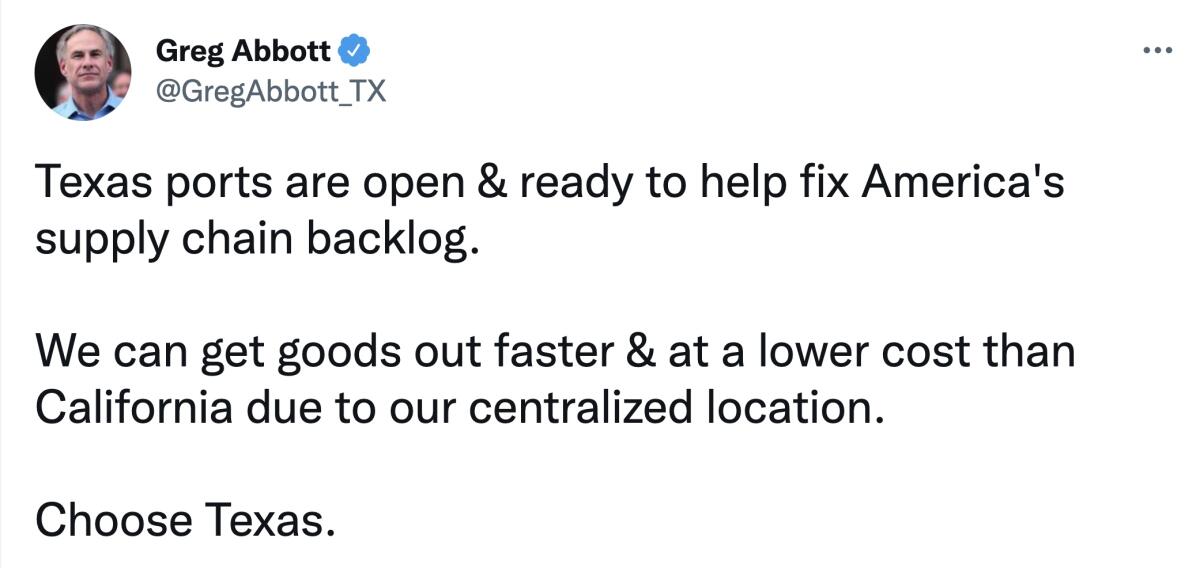

In a Nov. 1 tweet, the Republican governor wrote, “Texas ports are open & ready to help fix America’s supply chain backlog. We can get goods out faster & at a lower cost than California due to our centralized location.”

Sending more ships to Houston really isn’t the solution.

— Sal Mercogliano, shipping expert

Is this practical or plausible? Sadly, no. So impractical, in fact, that Robert Khachatryan, chief operating officer of the Southern California freight forwarding firm Freight Right, told me he regarded Abbott’s statement as “almost satire.”

Perhaps it was. But it was also part of Abbott’s general schtick about Texas’ allure for business. The problem with his take is that it falls into the category of braggadocio that Texans describe as “All hat, no cattle.”

Let’s take a look.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Although the video accompanying Abbott’s tweet advises businesses to “Escape California — everyone is doing it,” metrics compiled by Bloomberg underscore how badly Texas’ economic performance pales next to California’s.

Over the four quarters that ended in June 2021, Texas was the 15th-worst-performing state in the Bloomberg Economic Evaluation of the States index, which is based on job creation, personal income, home prices, mortgage delinquencies, tax revenue and stock values of state-based companies. California ranked first.

Other figures support Bloomberg’s judgment. California’s gross domestic product rose by 21% over the five years that ended in June; Texas’ by 12%. Texas may be growing faster than California in population, but its per capita economic growth is not: from 2010 through 2019, per capita GDP in Texas grew 19.6% (to $61,682), in California by 28% (to $70,662).

Texas gets the headlines by attracting a few high-profile entrepreneurs, as it did when Elon Musk announced that he was moving the headquarters of Tesla to Austin from Palo Alto. Abbott crowed at the time that Musk “consistently tells me that he likes the social policies in the state of Texas.”

Musk may be telling the truth about his headquarters move, or he may not be; with Musk, it’s always better to wait until he fulfills a promise than to take it as a done deal.

Still, Bloomberg observes that “the market capitalization of the top 10 firms in Texas averages just $184 billion, far smaller than the average of $1.43 trillion in California.” Even if Tesla does move, its $1.2-trillion market capitalization is swamped by that of two of the most prominent California companies — Alphabet, the parent of Google, at $2 trillion and Apple at $2.5 trillion.

No surprise: Business leaders’ answer to the port backup is to eviscerate environmental and labor regulations.

The social policies implemented by Abbott may not do much to burnish Texas’ reputation for business-friendliness. The state’s horrific new antiabortion law won’t make it easier for Texas employers to recruit women of childbearing age, assuming it’s upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Abbott’s defense of the law’s ban on abortion even in cases of rape or incest — that “Texas will work tirelessly to make sure that we eliminate all rapists from the streets of Texas” — suggests that (to paraphrase Joan Didion) “measurable cerebral activity is virtually absent” in the Texas governor’s mansion.

Nor has Texas shown much solicitude for the businesses that provide capital to help its economy grow. After the state enacted a law blocking local governments from working with banks that have cut ties to the gun industry, money center banks abandoned the state.

JPMorgan Chase said it would cease bidding for municipal bond underwritings in the state and Citigroup said it was considering the same step. Goldman Sachs pulled out of a state-level bond sale, citing the law.

This is how Republican political posturing can have real-world financial consequences.

That brings us back to the port situation.

Juan Lara was headed back to the Port of Los Angeles two weeks ago from his daily pickup in the Mojave Desert when his truck erupted with engine trouble.

It’s all well and good to depict the shipping logjam as a problem of the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, except that it would be wrong.

The Southern California ports have come to symbolize what is in fact a problem for most ports in the U.S., because they’re the biggest, handling some 40% of all incoming cargo. A similar crisis, driven largely by the surge in traffic, afflicts ports all along the West Coast as well as in the Gulf of Mexico and the Eastern Seaboard.

Houston, the largest port on the Gulf of Mexico, is already overwhelmed by its own surge in traffic.

“You see three or four ships at a time show up, which really puts a stress on our terminals because we can’t handle that much cargo,” Port Houston Executive Director Roger Guenther told local reporters after Abbott’s tweet. “The cargo sitting on our terminal doesn’t have really a place to go.”

The port is suffering from a shortage of drivers and trucks not unlike that at the L.A./Long Beach ports.

Another issue is that some cargo redirected from California to Houston would end up in the wrong place. Goods scheduled for the West Coast would have to be shipped back west once they’re offloaded.

“To say that somehow we can solve this problem or help the congestion by moving vessels to Houston,” Khachatryan says, “is going to cause a lot of havoc.”

Houston can’t manage anything near the volume of Los Angeles and Long Beach. In 2020, the Southern California ports handled nearly 9.3 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units, the standard volume metric in ocean shipping; it refers to 20-foot containers, even though most oceangoing containers today are twice that size). Houston handled about 2 million TEUs.

Unemployment benefits didn’t keep Americans from returning to the workforce, since they’re still not clamoring for lousy jobs even after those payments have expired.

To put it another way, Houston last year handled about 2.9 million containers, the equivalent of two months of traffic at Los Angeles/Long Beach. Both locations have been operating near capacity. “Sending more ships to Houston really isn’t the solution,” says Sal Mercogliano, a maritime historian and expert in mercantile shipping at North Carolina’s Campbell University.

The video posted with Abbott’s tweet stated that cargo can sail from California to Texas gulf ports in “less than two weeks.” Logistics experts scoff at the estimate.

The route requires passing through the Panama Canal, which already has a wait time of eight to 10 days, Mercogliano says. That’s a product both of increased traffic demand and the canal’s tendency to periodically reduce the permissible size of ships passing through when its water levels fall because of drought conditions.

Shipping to Houston from China is more expensive to begin with, by as much as $8,000 per 40-foot container, the difference between the lowest rate of $10,000 to Los Angeles and the top quoted rate recently of more than $18,000.

Some shippers may already be scheduling cargo originating in China to the gulf or East Coast. That includes national retailers with volumes large enough to fill their own chartered ships, such as Home Depot or Costco, which theoretically can deposit their goods in warehouses anywhere in the country and move it to their stores as needed. But that’s not a solution for smaller shippers that have scheduled their goods for specific locations.

One other aspect of the shipping logjam that Abbott may not have recognized is that vessel operators have little incentive to reroute ships anchored off the California coast, Mercogliano says.

In fact, they’re profiting from the shortage of shipping capacity created by having a flotilla of carriers stuck at anchor. Shipping rates from China to the West Coast ran about $1,500 to $2,500 per container in the pre-COVID months; the latest quotes are running at nearly $19,000 — and some shipments are being booked into next year at today’s rates.

Sure enough, the vessel lines’ profits are soaring. The Copenhagen-based international line A.P. Moller-Maersk, for example, recorded a record profit of $11.9 billion on revenue of $43.3 billion in the first nine months of this year, up from a $2-billion profit on $28.5 billion in revenue for the same period last year.

“The clients” — that is, the goods’ owners — “are screaming,” Mercogliano told me. As for the vessel operators, “they’re getting paid more for terrible service.”

Logistics experts believe that the one certain solution to the port logjam is the passage of time, with the end possibly not coming until spring, when holiday demand will be well in the past and the staffing and road and rail infrastructures at the ports can once again manage the traffic.

In the meantime, preening politicians like Abbott will continue trying to exploit the situation as best they can. Shippers and consumers would do well to ignore them.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.