Facing ‘air rage’ when you fly? One airline has a solution

On a recent American Airlines flight, a frustrated passenger couldn’t squeeze her large luggage into the overhead compartment, and when a flight attendant told her she needed to check the bag, she lost her cool.

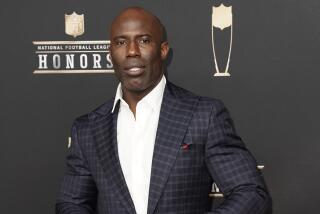

“You check it,” the passenger said, flinging the bag at flight attendant Teddy Andrews, who said the carry-on hit him. “Airline rage has been around for a long time but as of late it has gotten out of hand,” the veteran flight attendant said.

Andrews reported the angry flier to superiors to have her banned from flying American Airlines again, a decision that each carrier can make on its own without government oversight.

Airlines are debating a new effort to address air rage by having airlines share with one another their lists of passengers banned from flying because of unruly behavior. By sharing their lists, airlines may prevent passengers who are banned from one airline from flying on another. But the idea has already drawn opposition and concerns that sharing the lists could violate privacy and antitrust rules.

The debate over the lists of banned fliers began when executives at Delta Air Lines issued a memo to employees last week, saying the company is willing to share its list of more than 1,600 banned passengers with other carriers and calling on other airlines to do the same.

“A list of banned customers doesn’t work as well if that customer can fly with another airline,” Kristen Manion Taylor, Delta’s senior vice president of flight services, said in the memo.

The proposal came the same week a congressional committee held a hearing on the increasing problem of air rage triggered primarily by too much alcohol among passengers and a mandate that everyone onboard wear masks.

COVID-19 has thwarted the expected return of business travel and pushed flight prices down — for now. Holiday travel bookings are already on the rise.

At the hearing, Sara Nelson, president of the Assn. of Flight Attendants-CWA, which represents nearly 50,000 flight attendants at 17 airlines, submitted several recommendations to address the growing hostility on planes, including the creation of a centralized list of banned passengers that airlines can access.

“Flight attendants and gate agents have experienced incidents of verbal abuse, yelling and swearing in response to instructions, shoving, kicking seats, biting, punching, throwing trash at workers,” she said.

Southwest Airlines executives have already spoken out against the idea of sharing lists. Other carriers are not publicly commenting on the idea, while industry experts say the proposal raises privacy, antitrust and operational hurdles.

“This is the kind of thing that is easy to talk about but difficult to implement,” said Henry Harteveldt, an airline expert and president of Atmosphere Research Group.

In a statement, Southwest Airlines said it will continue to meet with other airlines and federal agencies to discuss ways to “prevent unruly situations and conflict escalation,” but “we do not publicly disclose the details of our restricted travel list.” Representatives for the carrier declined to elaborate.

Since January, airlines have reported more than 4,000 cases of unruly passengers to the Federal Aviation Administration, with more than 3,000 related to passengers violating mask rules. A survey of flight attendants this summer found that 85% had had at least one run-in with an unruly passenger and 17% said they were involved in an incident that turned physical.

Flight attendants and industry experts say masking rules are behind much of the angst. Excessive drinking, before and during flights, is also leading to dangerous behavior.

The rise in cases of air rage prompted the FAA in January to adopt a “zero tolerance” policy that replaces warnings and counseling requirements with stiff civil fines for misbehaving passengers. So far this year, the FAA has imposed more than $1 million in fines against passengers who have argued, hit, cursed, threatened or assaulted flight attendants or other passengers.

Delta’s proposal for a shared list of banned passengers would be separate from the federal “no fly” list that attempts to keep people with suspected links to terrorism off planes.

United and American Airlines declined to comment on Delta’s list-sharing proposal, referring questions to Airlines for America, a trade group that represents the nation’s airlines. The trade group said in a statement that it has encouraged federal agencies to prosecute passengers who are disruptive or unruly on a plane, but the group would not address the idea of sharing banned-passenger lists.

United has banned about 730 passengers for refusing to abide by the mask mandate. American Airlines would not disclose how many passengers are banned from flying on its planes.

In a statement, Alaska Airlines said it is working with Airlines for America and the FAA to improve flight safety. The Seattle-based carrier has more than 870 passengers on its banned list. It also declined to comment on the prospect of sharing this list.

Industry experts say the exchange of banned-passenger lists can be a problem because each airline may have different definitions and thresholds for unacceptable behavior.

As the cruise ship industry tries to turn a corner on the pandemic, the Grand Princess will depart from the Port of L.A. on Saturday.

Antitrust laws prohibit airlines from collaborating with competitors on routes, prices and other business strategies, prompting some industry experts to wonder whether sharing passenger names could constitute a violation of these laws.

There are also administrative questions. Before airlines can share their lists of banned passengers, the carriers need to decide who is going to collect and manage the list, Harteveldt said. Also, airlines may be forced to adopt an appeals process so that passengers who believe they have been unjustly banned can make their case to be taken off the list, he said.

Robert Ditchey, an aviation consultant who co-founded America West Airlines, said such lists could cause confusion if the airlines simply share common names such as “John Smith.” Additional information must be shared to distinguish a banned passenger from someone who has the same or a similar name, he said.

“So what else would you need to share?” he asked. “Your frequent flier number? Your email address? Your credit card information?”

Andrews, the American Airlines flight attendant who also testified before Congress about air rage, said he has submitted the names of several passengers to be banned from his carrier, most often for refusing to wear a mask or for being drunk.

The suggestion that airlines share their list of banned passengers makes sense, he said in an interview.

“If you are not agreeing to it, you are saying it’s OK for passengers to act irate on one airline and then [after getting banned] walk down the terminal and get on another airline.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.