Column: The government lawsuit against Kaiser points to a massive fraud problem in Medicare

For the better part of a decade, a time bomb has been ticking at Oakland-based Kaiser Permanente — an accumulation of allegations that the giant health plan systematically defrauded Medicare by overstating the severity of its patients’ medical conditions.

On July 30, the bomb detonated. That’s when the Department of Justice joined six lawsuits filed by Kaiser employees since 2013 asserting that they witnessed the alleged fraud.

The government’s action instantly brought those lawsuits, which had been filed under seal in federal court in San Francisco, into the daylight. Taken together they allege wrongdoing on a stunning scale; plaintiffs’ lawyers involved in the cases say hundreds of millions of dollars in penalties and damage claims may be at stake.

Medicare Advantage organizations...have some incentive to improperly inflate their enrollees’ capitation rates, if these organizations fall prey to greed.

— U.S. Magistrate Laurel Beeler

At this stage, none of the allegations has been proved in court. Kaiser denies them, stating that it has been compliant with the rules governing Medicare claims and intends to “strongly defend against the lawsuits alleging otherwise.” It says it’s “disappointed the Department of Justice would pursue this path.”

But the allegations, and the Department of Justice’s decision to support them by becoming a co-plaintiff against Kaiser, point to a larger issue with Medicare — specifically, the Medicare Advantage program, which allows private health insurers rather than government administrators to provide coverage to seniors. The indications are that Medicare Advantage is profoundly infected with fraud.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Recently, the federal government has joined in private lawsuits against a host of major healthcare providers and health insurers.

“It’s industry-wide and it’s of major proportions,” says Mary Inman of Constantine Cannon, a law firm specializing in whistleblower cases, which numbers one of the Kaiser whistleblowers among its clients.

Inman says every major health insurance company has faced these allegations; a cottage industry has sprung up of firms purporting to help Medicare providers make “accurate” filings with the government but, in fact, showing them how to game government rules. “It’s not going away any time soon,” she says.

In recent years, the government has extracted settlements from several healthcare providers accused of exaggerating patient conditions to inflate Medicare Advantage fees, which are based partially on “risk scores,” assessments of the health of individual enrollees.

The resolutions included a $270-million settlement in October 2018 from El Segundo-based Healthcare Partners and a $30-million settlement in April 2019 from Sacramento-based Sutter Health. The companies settled without admitting to the allegations.

A major case brought against UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest health insurer by membership, is pending in Los Angeles federal court, with a trial date not scheduled until 2023. The DOJ filed a case last year against Anthem, the second-largest insurer, in Manhattan federal court. A settlement in another case against Sutter Health is expected to be announced imminently. UnitedHealth, Anthem and Sutter didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Pfizer and Moderna will rake in the big bucks from their COVID vaccines. That’s a sign of a broken system.

The Advantage program isn’t the only generator of fraud complaints in Medicare. In 2018, for instance, Ontario-based Prime Healthcare paid $65 million to settle charges of overbilling Medicare. The hospital network didn’t admit to the allegations.

Medicare Advantage was designed in part to counteract a structural flaw in Medicare — because the program paid doctors a fee for each service they rendered, it carried a built-in incentive for doctors to do more than their patients needed, merely to jack up their billings.

Under Medicare Advantage, health plans are paid a set amount per patient per month, known as a capitation. If the doctors overprescribe, they could lose money on patient care; if they keep services under control, they pocket more of the capitation for themselves.

The stakes in the fraud cases are immense. Medicare Advantage risk adjustments average $3,000 per year for every documented condition. That can double the capitation rates for enrollees with multiple risks. In 2013 alone, according to an audit by the Government Accountability Office, Medicare overpaid Medicare Advantage providers $14.1 billion, primarily because of “unsupported diagnoses.”

“Unfortunately, human nature being what it is,” U.S. Magistrate Laurel Beeler observed last year in rejecting Sutter Health’s motion to dismiss the case against it, “Medicare Advantage organizations ... have some incentive to improperly inflate their enrollees’ capitation rates, if these organizations fall prey to greed.”

The Kaiser allegations may be the most explosive because of its unique position in American healthcare.

“They’re the mother of managed care,” Inman says. “There’s something really significant about them being engaged in this practice. They’re seen as a leader, and for them to stoop to doing this shows how irresistible the notion is of increasing your risk score to increase your reimbursement from Medicare.”

She might have added that the allegations, if true, are particularly deplorable given that Kaiser is a nonprofit organization.

Several factors could account for the apparent explosion in fraud allegations in Medicare. One is the federal False Claims Act, which Congress upgraded in 1986 to ensure whistleblowers of a sizable share of recoveries from cheating government contractors — up to about 25% in cases in which the government participated as a plaintiff, and 30% if they pursued claims on their own.

That inspired a surge in “qui-tam” lawsuits — the term comes from the Latin for “in the name of the king” — by whistleblowers.

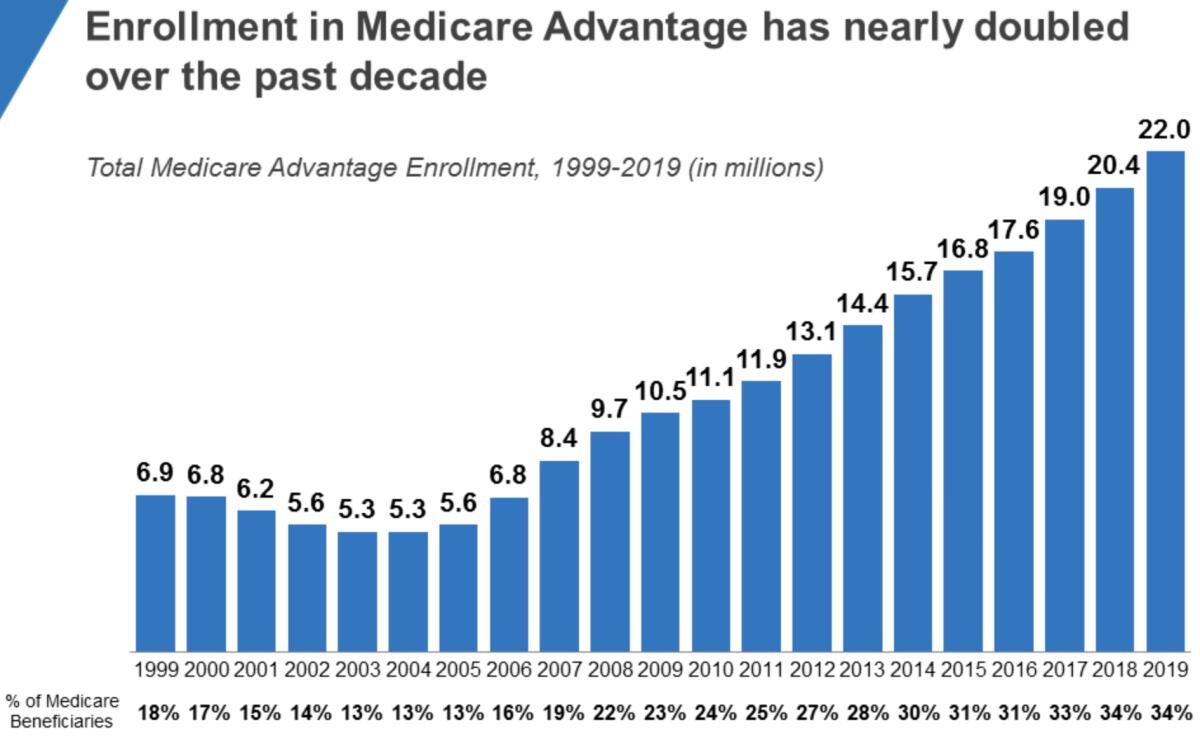

Another is the maturity of the Medicare Advantage program, which was established in the 1970s to allow seniors to receive Medicare services through private health insurers rather than the traditional government-administered program.

Private health plans love Medicare Advantage. It attracts a generally healthier customer base than traditional Medicare, so much so that critics have consistently maintained that capitations exceed what’s necessary to serve enrollees and provide health plans with a reasonable profit.

The health plans can obtain increased capitations for individual patients by showing that they’re victims of specific ailments that are especially costly to treat, such as diabetes, stroke or pulmonary problems, a process known as risk-adjustment.

The health plans have strived to attract more enrollees — and healthier ones — by offering such ancillary services as health club memberships and vision and dental care, some of which can be obtained only by enrolling in “Medigap” plans that cover services unavailable through traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage enrollment has been growing sharply in recent years, reaching 22 million, or 34% of all Medicare enrollment, in 2019.

It should be clear that health plans have two main ways to maximize their Medicare Advantage profits — by cutting costs, or increasing risk-adjustment payments.

When big hospitals merge, the merger partners’ mantra is almost always the same: The deal will deliver lower costs to the lucky patients, with no sacrifice in quality.

To regulate the latter, Medicare imposes limitations on risk-adjustment claims: They can’t result merely from radiology or laboratory tests but must reflect face-to-face encounters between doctor and patient that result in treatment, and those encounters must be thoroughly documented.

An analysis of the numerous false claims lawsuits currently filed against major healthcare providers suggests that the industry has been extremely creative at circumventing these rules.

In a review of the risk-adjustment landscape for an industry conference in 2012, Inman reported that the dodges ranged from simply making up diagnoses and treatments, to exaggerating the severity of a patient’s condition, to claiming that a patient was being currently treated for a condition such as stroke or cancer that had actually been treated in the past.

“You could have a patient with minor depression who’s suddenly upcoded to major depression,” Inman told me. “You see prevalence rates for some conditions that are not consistent with what you would expect to see in the general population. We were seeing cases of malnutrition that you weren’t expecting to see anywhere outside sub-Saharan Africa.”

Until recently, government auditors could be relied on to be asleep at the switch, in part because they were outgunned by healthcare providers. That may have encouraged more gaming of the system. The spate of recent cases may indicate that they’re waking up.

These cases typically aren’t resolved quickly or easily. They start with the filing of a qui-tam lawsuit under seal, with the hope of persuading the government to perform its own investigation leading to its intervention as a co-plaintiff with the whistleblower. Those investigations can take years, during which the individual plaintiffs’ cases are placed in abeyance so as not to interfere with the government probes.

That brings us back to the allegations against Kaiser, which have been disclosed as a result of the government’s intervention.

Making a profit in the hospital business is tough.

In a case filed in 2013, data quality employee Ronda Osinek says that around 2007, Kaiser started “diagnosis chasing” — poring over patient data for conditions such as diabetes, kidney disease and depression that would warrant claiming higher-risk reimbursements.

Some of these inquiries required physicians to amend their patient files, sometimes months after the patient visits, she says. Kaiser even seemed to suggest the language to use so that several bore comments such as, “After reviewing the notes from the aforementioned visit, I recall the visit,” accompanied with a revised diagnoses and treatment. Kaiser held “mandatory ... ‘coding parties’” at which doctors were gathered in a room with computers and instructed to look for possible revisions in their patient notes.

In a case filed in 2014, James M. Taylor, then a Kaiser doctor with an expertise in medical coding, alleged that Kaiser ignored his efforts to correct systematic errors in its submissions to Medicare. Taylor also asserted that Kaiser was considerably more diligent in ferreting out coding errors that had led to lower reimbursements than errors that had produced overpayments — and that it failed to report some overpayments that it was required to return to the government.

Taken at face value, the allegations against Medicare Advantage organizations imply a stupendous misdirection of government resources into the wrong hands. The GAO estimated in 2014 that almost 10% of the payments to Medicare Advantage organizations were improper. Given that Medicare Advantage providers were paid about $290 billion last year, that means some $30 billion a year may be going astray.

That’s money that could be used for a host of goals other than fattening the budgets of healthcare companies: funding universal coverage, reinvigorating the nation’s tattered public health infrastructure, you name it. The profit motive has long been a huge drag on the American healthcare system, but it’s much worse when the profits are dishonestly obtained.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.