A Pasadena startup got billions selling COVID tests. Then came questions

In the last year, executives at a Pasadena startup began flying from Burbank to destinations around the world on a pair of newly registered Gulfstream jets, one a G650 decked out in white plush seats, burnished interiors and other luxury finishes.

Two executives associated with the same company also bought multimillion-dollar homes not far from the startup’s posh headquarters. And when Realtors asked for proof they could pay such prices, one of the executives handed over a bank statement showing a $128-million deposit into the company’s account from the British government.

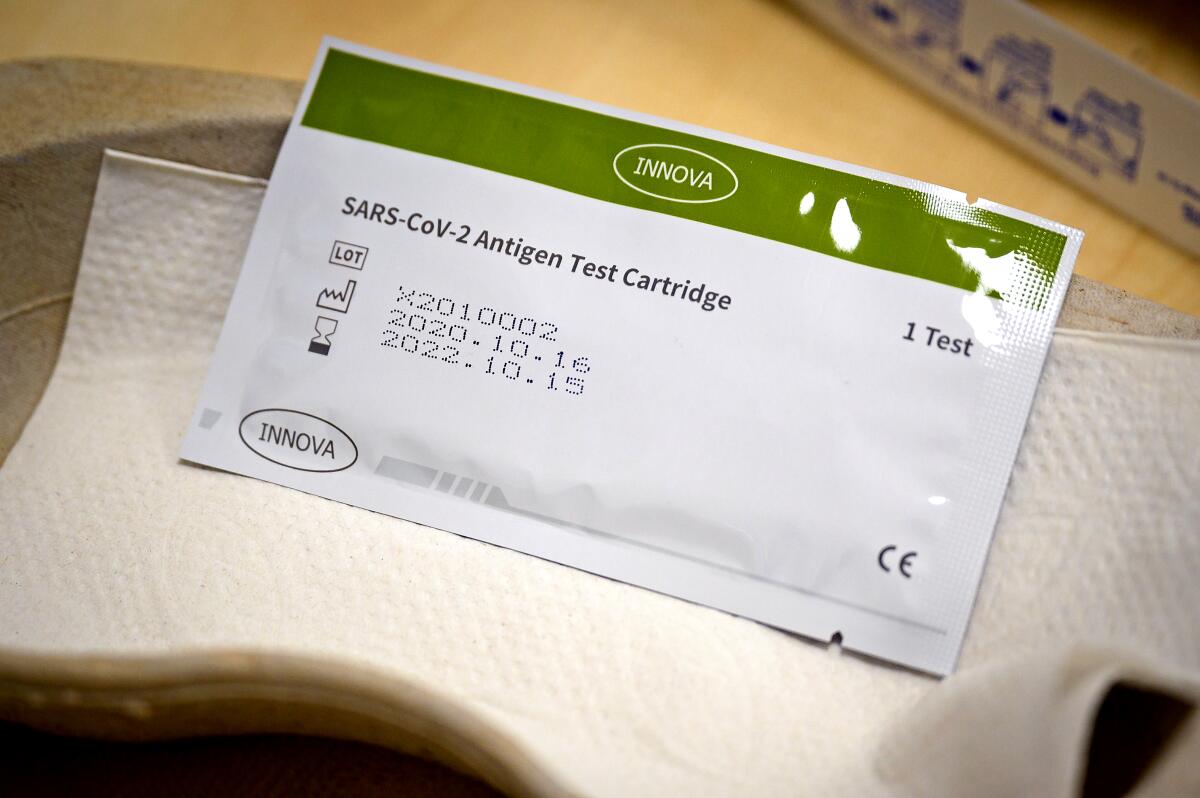

The recipient of that massive windfall was Innova Medical Group, a company formed at the start of the pandemic that became an unlikely global supplier of coronavirus tests.

It was founded by Charles Huang, a 57-year-old former Chinese auto executive who settled in the San Gabriel Valley and is no stranger to ambitious ventures — including separate efforts to help revive the storied British carmaker MG Rover and to build a $4-billion hybrid vehicle plant in Alabama.

Neither of those ventures panned out, but that didn’t discourage Huang. When China disclosed that some residents of Wuhan — where Huang had gone to college — had fallen ill from a newly discovered coronavirus, he sensed an opportunity.

Less than three months later he was president of Innova, which in September 2020 secured a vast supply of rapid coronavirus tests from an obscure Chinese manufacturer before established pharmaceutical companies could do so.

So when British Prime Minister Boris Johnson became desperate for tests that would allow the country to return to normality, Innova was ready: It secured multiple government contracts estimated to be worth at least $2.7 billion and has sold more than 1 billion tests worldwide.

But Huang’s financial score has been dogged by controversy.

In June, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration said it had “significant concerns” that Innova’s test could produce false results leading to serious illness or death. The agency urged the relatively few Americans who had received Innova’s product to “destroy the tests by placing them in the trash.”

The warning followed an inspection earlier this year of Innova’s offices, where FDA officials found things in disarray.

Inside a storage room, government inspectors found 13 cartons of tests commingled with boxes of the product damaged or set to be destroyed, with no markings indicating which boxes were OK to ship, according to an FDA letter sent to the company. Tests had been shipped with the wrong instructions, the inspectors found. And Innova had not inspected or otherwise verified its tests after receiving them from its manufacturer in China.

Innova also had distributed more than 70,000 of the tests to Americans, the FDA said, though the agency had not authorized them for domestic sale despite an application to do so by the company.

Innova defended its product, which it continues to offer in the United Kingdom and other foreign markets. A spokeswoman asserted that the FDA’s concerns are unrelated to the performance of the test but rather such issues as labeling.

Innova is working with the agency to rectify any problems, she said, adding that U.S. sales were limited to employees, clinical studies and some customers for evaluation purposes.

“We are confident that we are on the pathway to fully comply with FDA requirements,” the spokeswoman said in an email.

She declined to make Huang available for an interview or answer other questions raised in this story not directly related to the company’s testing business.

In Britain, the FDA action in June inflamed an already intense debate in the media and scientific publications over the accuracy of the tests and a decision by the U.K. government to mail millions to homes for mass screenings — even though the manufacturer’s own instructions say they are intended to be administered to patients with symptoms by “trained clinical laboratory personnel.”

It’s not the first time that a group of little-known entrepreneurs has made a fortune selling a coronavirus test that is facing questions from regulators. In the United States, L.A.-area startup Curative grossed $1 billion or more on its tests after health officials across the country embraced them as a way to test mass populations — even though they also were intended only for patients with symptoms. In response, the FDA issued a public reminder about the tests’ approved usage.

Curative’s mouth swabs should be administered only under strict protocols, federal regulators caution. Fred Turner, Curative’s 25-year-old founder, thinks otherwise.

Jo Maugham, executive director of the Good Law Project, a nonprofit that sued the U.K. government to reveal the details of billions of pounds of spending related to COVID-19, said the pandemic opened the floodgates for questionable contracts.

“Governance has fundamentally disappeared,” he said. “Lots of things are happening, for reasons that are very, very difficult to understand.”

This much is certain. In the pandemic’s earliest months, Huang saw an opportunity — illustrating how, in the chaos of a world-changing event, industrious entrepreneurs even without a track record in health or science could profit wildly.

Fast, cheap and controversial

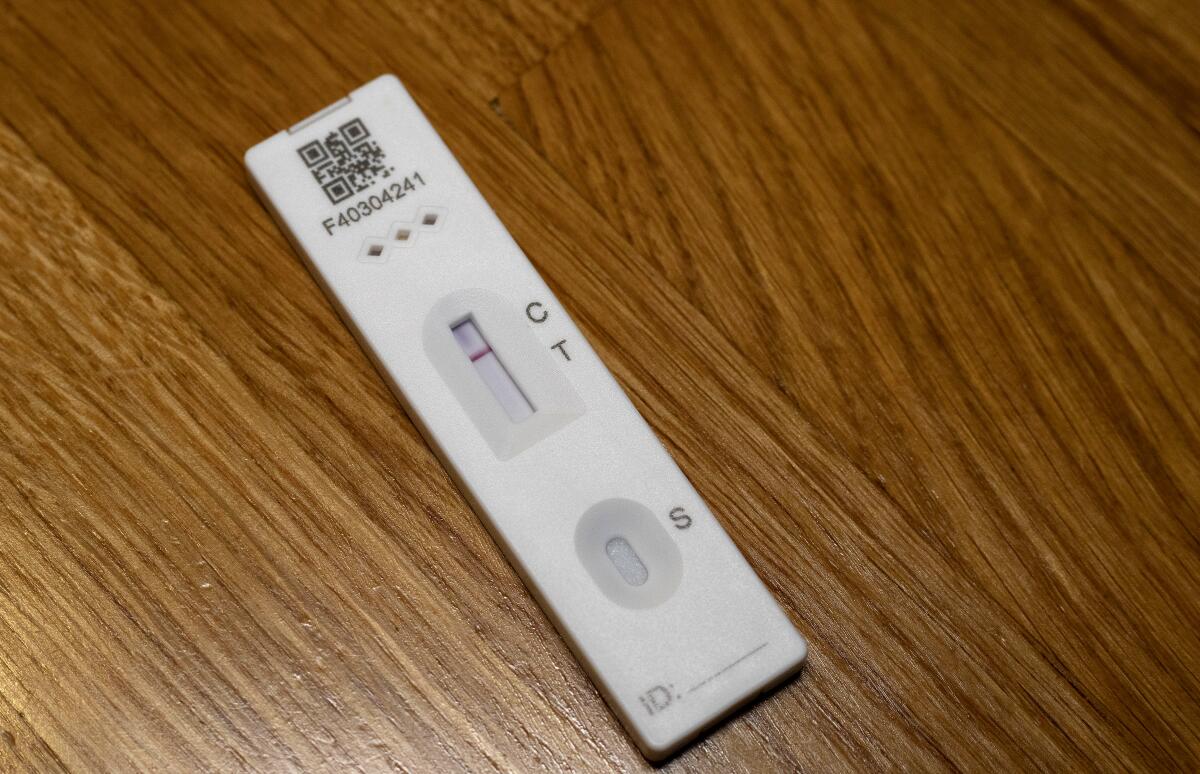

Rapid antigen tests are similar to do-it-yourself home pregnancy tests, only Innova’s rely on nasal and throat swabs. They look for proteins tied to coronavirus infections, a method that is less sensitive than polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests that detect genetic material from the virus.

Yet antigen tests hold an advantage over PCR analysis in price and speed. PCR tests can cost $100 or more and must be processed in labs, with results often taking days. Antigen tests can provide results in 20 minutes and Innova says its test costs “less than a coffee and a muffin” when purchased in large quantities.

Proponents, including Innova, claim the tests’ lower sensitivity makes them better at detecting contagious people with high viral loads, a point up for scientific debate.

The decision by the U.K. government to buy the antigen tests in massive quantities from the Pasadena startup was rooted in the desire by Johnson’s government to reopen the economy after shutdowns.

His government established a test-and-trace program that was built around antigen testing to rapidly catch and isolate coronavirus patients, including those who are asymptomatic.

Government and Oxford University scientists evaluated 40 tests and selected Innova’s for a pilot program based on the initial study. The tests are made by Xiamen Biotime Biotechnology Co., a company in Fujian province.

The government said the test produced fewer than one false positive out of 100 and overall caught about 77 infections out of 100, including more than 95% of those with high viral loads. Its sensitivity, or ability to detect infections, increased to 79% when administered by laboratory scientists.

Other people in the initial studies tested themselves even though Innova’s own instructions say the tests should be administered by healthcare professionals to patients with symptoms. That discrepancy forced the government to repackage the Innova test as a National Health Service test, allowing it to be self-administered by people without symptoms. The test caught only 58% of infections when self-administered.

Results of the Liverpool pilot project released in December were even less promising, finding that self-administered Innova tests caught just 40% of infections. A later study conducted of University of Birmingham students released in April found the Innova tests were ineffective at detecting people at either the very early or very late stages of infection.

“This is being promoted as a way of opening up society to say that these tests make people safe, when actually, that performance is too poor to do that,” said University of Birmingham biostatistician Jon Deeks, a leading critic of the government’s testing program. “You might pick up some cases, and that’s a good thing. But if you’re using them to say people haven’t got COVID, they’re not good enough to do that.”

Dr. Tim Peto, an Oxford University scientist who led the initial government study, said Innova was chosen after its test “passed the threshold of performance” and it became clear the company could supply the test in large quantities.

“It wasn’t taken forward because it was clearly the best of the bunch. It was the one that was available,” he said.

The startup has defenders in the public health sector, including Michael Mina, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has thrust himself into the U.K. debate.

“I know people want to hate on the government for purchasing tests — but the Innova test is working entirely as expected,” Mina tweeted to his more than 100,000 followers Jan. 12. “Very good for detecting contagious people. Which is the only goal here. I’d be happy to write an OpEd for @guardian to explain.”

Mina has received consulting and speaking fees from some manufacturers of rapid coronavirus tests. A Harvard spokeswoman said that Mina was not available for comment but that he had not received money from Innova.

Innova has leveraged Mina’s advocacy. Its website links to an interview with Mina by the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. headlined “Could quick COVID ‘antigen’ tests break the back of the pandemic?”

Mina led a pilot program at Citibank in which bank employees in New York and Chicago checked themselves three times a week with Innova’s tests. In March, Innova hired away Sean Rogers, a Citibank executive who had worked on the pilot, to be its new chairman. The bank has since decided to use another antigen test that, unlike Innova’s, has been authorized by the FDA.

The British government, however, has continued to distribute the Innova tests despite the FDA action. A spokesperson for the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care noted the government’s “rigorous” assessment process and “robust quality assurance process” in making that decision.

“We have confidence in [antigen] lateral flow tests, which help us identify people without symptoms but who could pass the virus to others — helping break the chains of transmission,” she said in an email.

The Innova spokeswoman defended the company’s antigen test, saying that self-administered results should improve as users take multiple tests.

“The sensitivity of the test may drop when the test is administered NOT following the instructions. But [the] antigen test itself is a simple and easy test. We accept that layman and first-time untrained users may have questions regarding the proper application of the test,” she said.

She also noted that a more detailed analysis of the Liverpool study released in July found that the tests had led to a 21% reduction in coronavirus transmissions. Depending on the statistical model, that could have prevented 850 to 6,600 cases.

Making the big time

Allyson Pollock, a public health professor at Newcastle University in England who has tracked Innova’s U.K. contracts, estimates they total $2.7 billion to about $4 billion. The BBC reported the company has delivered 1 billion tests to the British market. Innova declined to comment on its sales.

It wasn’t at all certain that Huang would reach that kind of success with Innova, a portfolio company of Pasaca Capital. The private investment firm was founded by Huang in 2016, according to Pasaca’s website and public records.

Huang, also known as Chunhua Huang, got an economics degree at Wuhan University before traveling abroad for a master’s in business administration and doctorate in marketing at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland. He worked as an investment analyst at major banks, including Credit Lyonnais, where he covered the Asian automotive, transport and infrastructure markets from 1996 to 2000, according to published biographies.

His Pasaca bio boasts of him “playing a key role in the strategic alliance” in 2002 between MG Rover Group and China’s Brilliance Group, a major commercial vehicle maker and the first Chinese company to go public on Wall Street.

But the alliance fell apart and the parent of MG Rover filed for the British equivalent of bankruptcy in 2005 after Brilliance’s chairman, Yang Rong, fled to the U.S. after accusations by Chinese authorities of economic crimes. Huang was Brilliance’s finance director, according to a British parliamentary report that investigated the MG Rover failure.

Rong, 64, also known as Yung Yeung or Benjamin Yeung, was ranked by Forbes as China’s third-richest man in 2001 with a net worth topping $800 million. He denied the accusations, and media outlets including the New York Times portrayed him as the loser of a power struggle and the victim of China’s desire to rein in its emerging class of ultra-wealthy entrepreneurs.

Huang retained his ties to Yeung, who resurfaced in 2009 telling Reuters in an interview from his Southern California home that he expected to build three multibillion-dollar plants that would make 3 million clean technology vehicles per year.

Shortly after, Hybrid Kinetic Motors — based in Pasadena, chaired by Yeung and vice-chaired by Huang — announced it had a deal with officials in Baldwin County, Ala., to build a $4-billion clean vehicle plant. The state’s governor attended the unveiling of the concept car, but the plans didn’t come to fruition when Hybrid Kinetic couldn’t raise the capital.

A spokesman for Yeung, who lives in the wealthy San Gabriel Valley community of Bradbury, said the businessman was not an investor in and had no ties to Innova or Pasaca Capital, though he and Huang remain friendly.

It’s unclear what led Huang to the import-export deal with the Chinese manufacturer Xiamen Biotime, but he had extensive experience in the China market. He was born in China, according to L.A. County voter registration records, and served in the late 2000s as director of China equity research for BNP Paribas, according to a bio.

A September news release on Xiamen Biotime’s website announcing the distribution agreement quotes Huang saying Innova had a “longstanding relationship with Biotime” but does not provide details.

Huang also says in the release, since taken down, that Innova chose its manufacturing partner after “validation testing completed by ourselves, our buyers, and other independent agencies proved time and time again” that it was the best test on the market.

A spokesman for Xiamen Biotime referred all questions to Innova, which did not respond to questions on this matter.

The payout

However Huang managed to secure his supply of antigen tests, the result has been lucrative for Innova.

After sharing an address last year at a Monrovia warehouse, Innova and Pasaca have moved into separate suites in a marble- and granite-clad Pasadena office building on Colorado Boulevard. Innova has since expanded its offices — where an enlarged image of the coronavirus hangs near the front desk — in a deal valued at $13.2 million.

The success has fueled a corporate and personal luxury buying spree.

An Innova subsidiary and Pasaca Capital registered two Gulfstream jets early this year, according to Federal Aviation Administration records. One was a Gulfstream 650, among the top corporate jets on the market. A new Gulfstream 650 costs more than $60 million. Pasaca’s jet was built in 2015.

Innova’s second Gulfstream, registered in February, was an older model that can spaciously seat 20.

In the San Gabriel Valley, three local real estate agents, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to nondisclosure agreements, said executives with the companies have been looking at estates in Pasadena, San Marino and Arcadia listed for anywhere from $3 million to $20 million over the last year.

Such tours aren’t given to just anyone. One agent said several executives, including Huang, flashed an Innova bank statement with a $175-million balance as proof of funds.

Real estate records show at least two properties were purchased by executives tied to Innova in the last year.

In October, Innova President and Chief Executive Daniel Elliott shelled out $4.1 million for an 8,000-square-foot mansion in Arcadia. According to the listing, the two-story showpiece includes six bedrooms, eight bathrooms, two kitchens, a sauna, wine cellar, movie theater and elevator.

Then in April, Weining Mao, president of the Charles Huang Foundation, paid $4.198 million for a traditional-style estate near San Marino’s Lacy Park. The 3,700-square-foot home claims nearly half an acre and comes with a swimming pool, spa, multiple entertaining areas and a bocce ball court set among manicured gardens.

New opportunities

The U.K. has one of the most successful vaccination programs in the world and lifted most pandemic restrictions in England on July 19. However, the government is urging people to continue testing as new strains spark an increase in coronavirus cases. The government announced this month that new studies show the Innova test is effective at detecting the Delta variant.

It’s unclear, though, how many people are following that direction. Users are supposed to register test results, but a recent audit of the test-and-trace program found that only 14% of the 691 million antigen tests distributed to homes, schools and elsewhere had been registered as taken by late May. It’s possible many more tests have been used, but it’s also possible many millions haven’t.

Amid the recent explosion of the Delta variant, Deeks of the University of Birmingham said he has been advocating people take the antigen tests, though there have been signs people haven’t been doing so.

“People’s interest in it has definitely dropped,” said Deeks, who noted that while schools were in session in the spring, teachers he knew talked of “cupboards full of tests.”

The Innova spokeswoman said there was still heavy demand for the test, noting it has been approved for use in more than a dozen countries, including France, Germany, Israel and Malaysia — and it is seeking additional approvals.

Innova has made two acquisitions in Southern California to expand its testing capacity and in May announced a deal to start producing millions of tests a day in the U.K.

“Innova has supplied more than a billion rapid antigen tests to the world and will continue to supply to meet customer demand,” the spokeswoman said.

Such demand may help explain why company executives are flying around the world. Flight records for the older jet show it has flown to Iceland, Qatar, Cyprus, Israel and France. The records are unavailable for the G650.

Still, Huang may be hedging his bets. Since Innova has achieved success, Pasaca has gone on something of an investment spree — and some of the companies don’t appear COVID-19-related.

In March, Pasaca announced a $50-million investment in Caton Technology, a Singapore firm developing “next-generation IP network transport solutions.”

And more recently, a new company appeared on the firm’s website. It’s a Rancho Santa Margarita company called Sweegen, described as providing “sweet taste solutions for multinational food and beverage manufacturers.”

The company, Pasaca said, “is on a mission to reduce the sugar and artificial sweeteners in our global diet.”

Times staff writers Roger Vincent and Andrew Mendez contributed to this report.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.