Column: Lazy TV news interviewers were Tom Barrack’s willing enablers

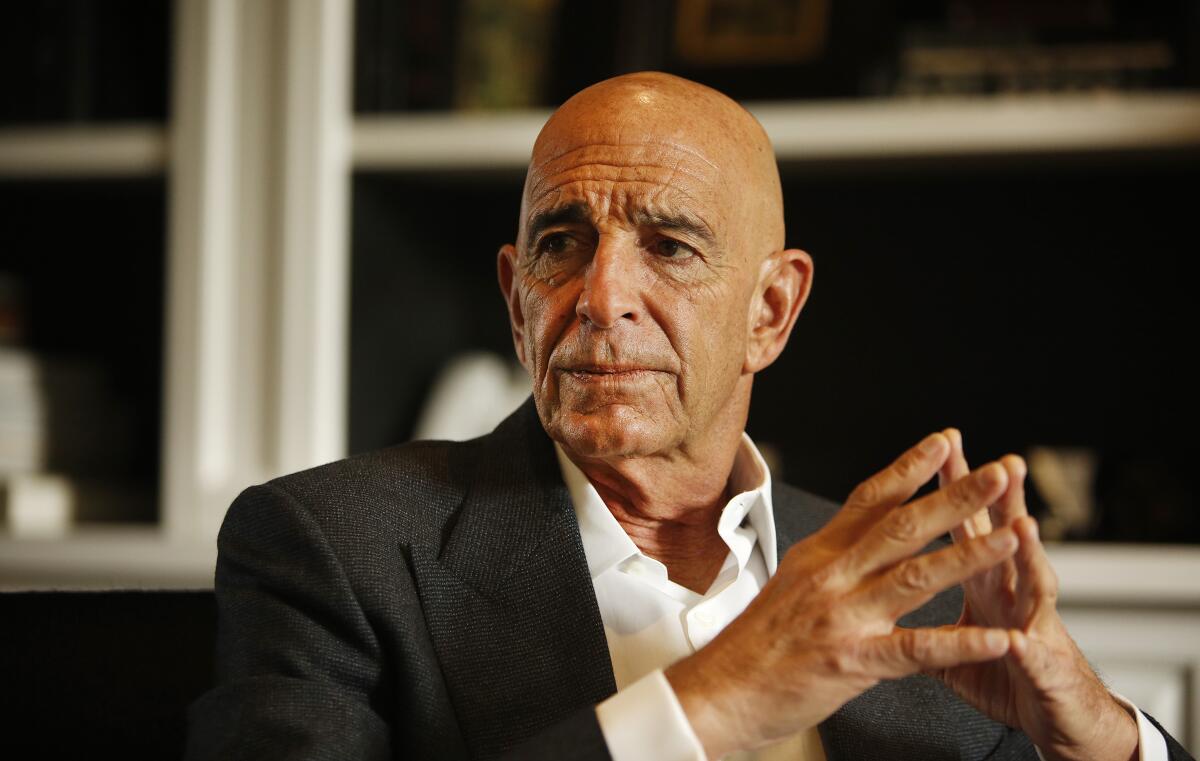

What most intrigued me about the federal indictment of Trump ally Thomas J. Barrack Jr. for acting as an unregistered agent of Arab regimes wasn’t the accusation itself.

If one takes federal prosecutors at their word, after all, the Los Angeles real estate investor comes off as just the sort of casual grifter and scofflaw who seemed to be hip-deep in Donald Trump’s inner circle.

Barrack, 74, is charged with violating a law requiring agents of foreign governments — in this case, the United Arab Emirates — to register with the Justice Department, and with lying to the FBI about his business arrangements.

In the UAE ... brilliant young leaders are crafting forward-looking policies to effectively forge a new Middle East.

— Thomas J. Barrack Jr., Fortune magazine

He was arrested Tuesday as the indictment was unsealed, and reached a deal to be released from custody on $250 million bail, with a court date in New York on Monday. A spokesperson says he’ll be pleading not guilty.

What caught my eye was the little mystery the prosecutors placed at the center of the indictment. Barrack achieved some of his goals, they say, through a series of six “nationally televised” interviews in 2016 and 2017.

The indictment doesn’t identify the national news programs that aired these interviews, but I tracked most of them down. Four of the six were aired on Bloomberg TV, and a fifth on the Charlie Rose program, which aired on PBS stations. I couldn’t find the sixth.

(I asked Bloomberg for a comment but didn’t hear back. Rose lost his TV gig in November 2017 over accusations of sexual harassment.)

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Watching these clips opens a demoralizing window into how easily television interviewers can be manipulated, especially by rich and well-connected guests. Barrack proved adept at exploiting a few well-known features of the television age.

One is TV’s tendency to take everyone at his or her own level of self-esteem. Another is the near-certainty that TV interviewers will come to the set utterly unprepared to ask their guests searching questions.

A third is the likelihood that people brought onto news sets as commentators are almost always angling to pitch a product — a book, a movie, a relationship with power. (As the author of several books, I am not immune to this impulse.)

Barrack was pitching two products in his TV appearances: overtly, his decades of friendship with Trump, which allowed him to claim unique insights about his character, and secretly (according to the prosecutors) his relationship with the UAE.

The TV interviewers didn’t care about the first, and probably wouldn’t have cared about the second even if they had known about it. Barrack was available to fill airtime, and that was plenty.

Barrack’s interviewers swallowed his assertions about the UAE as gospel — that they exemplified “good Islam” in distinction to violent Islamic terrorists, that they should be rewarded for standing as loyal and faithful allies of the U.S. in the war on terrorism, and that they were blessed with progressive young leaders.

During the CBS program “Face the Nation” on Sunday, moderator John Dickerson mentioned that among the Republicans who were critical of the Senate GOP’s Obamacare repeal bill was Ohio Gov.

Barrack’s UAE clients, according to the indictment, responded to almost every TV appearance with messages of praise and gratitude.

It’s proper to observe that Barrack wasn’t only pumping up the UAE and its sheikhs in these interviews; he was also pumping up Donald Trump, a longtime friend. In this guise he retailed an image of Trump that was manifestly and profoundly at odds with the image Trump himself projected in his own public appearances.

The idea was that ordinary people never got a glimpse of the real Donald Trump revealed to his intimates. Bloomberg titled a Barrack interview on May 31, 2016, “Tom Barrack: The Donald Trump I Know.”

“I know a little bit about the side [of Trump] that people haven’t seen,” Barrack told Bloomberg’s Erik Schatzker. “Competency, tenderness, kindness, compassion — not the harshness that appears.”

On Jan. 31, 2017, Barrack told Bloomberg that Trump “has a very smart group of people around him — Steve Bannon, Jared Kushner, Reince Priebus ...”

And on July 21, 2016, the last day of the Republican National Convention that nominated Trump, Barrack told Charlie Rose that the process of recruiting personnel for the more than 4,000 executive branch jobs in Trump’s gift had already begun and was “the best I’ve ever seen, the most methodical, the most thoughtful. ... He’ll surround himself with unbelievable talented people.”

The chaotic and catastrophic unfolding of the Trump administration over the subsequent four years is a reproach to all these honeyed words. If Barrack was really a witness to Trump’s management style in that period, then he must have been either blind as a bat or a consummate liar.

The economic rationale for President Trump’s trade war with China has been so threadbare and the likelihood of losses so great that no one should be surprised that it hasn’t been the success Trump predicted.

That brings us back to his promotion of the UAE in the media. In addition to Barrack’s television appearances, the indictment mentions an op-ed that appeared under his name in an unidentified national publication. The prosecutors’ references allow it to be identified as Fortune, where the piece in question was published Oct. 22, 2016.

“The Arab World’s best hope is the rise of a new generation in government,” the article said. “In the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, brilliant young leaders are crafting forward-looking policies to effectively forge a new Middle East.”

According to the indictment, Barrack’s UAE clients objected to parts of the draft op-ed referring to Middle Eastern “dictatorships” and proposed substituting the term “regimes.” The term “dictatorships” doesn’t appear in the published piece, but “regimes” is used repeatedly.

A few words about Barrack and his purported clients. Barrack, whose net worth was estimated by Forbes at $1 billion in 2013 (he dropped off the magazine’s billionaires list the next year), is the grandson of Lebanese Christian immigrants, grew up in Culver City and graduated from USC.

He’s the founder of Colony Capital, a real estate investment firm. In his television interviews, he frequently invoked his Middle Eastern roots to explain his interest in the region and ostensible insights into Arab political thinking.

The UAE is a federation of seven oil kingdoms bordering the Persian Gulf, of which the most important are Abu Dhabi and Dubai. Traditionally they’ve been close allies with the U.S. as well as Saudi Arabia.

According to the indictment, in June 2016 the UAE launched a campaign “to promote its foreign policy interests and increase its political influence in the United States.” The Emirates reached out to Barrack to draft the strategy and also provide investment advice.

In a new ranking by historians, Donald Trump only ranks fourth as worst U.S. president ever. How can that be?

Prosecutors say that through his associate Matthew Grimes, who is also under indictment, Barrack submitted a proposal in December 2016 that would also help the UAE “garner political credibility for its contributions to the policies” of Trump, who had just been elected president.

The string of media appearances cited in the indictment began on May 31, 2016. On that date, Barrack was interviewed on Bloomberg TV. “The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia and Israel in my opinion will align as allies very quickly, and the world could change for the better,” he said. “All three of them, I guarantee you, want terrorism to go away.”

He added, “we should reward our energy-producing Middle East partners who are helping us stamp out terrorism at home and abroad.”

Barrack sent a link to the interview to the Emirates, and asked whether there was anything they wanted him to discuss in a subsequent interview that he hadn’t mentioned, according to the indictment. They said they’d get back to him. But his UAE contact later emailed him to say that Emirate sheikhs were “extremely impressed and happy” with the interview. “You are the new trusted friend!”

On June 2, 2016, the indictment says, Barrack emailed the anchor of an upcoming interview to say he wished to discuss Middle East issues on the air. It’s unclear whom the email was directed to, but a Bloomberg interview aired on July 18 and the Charlie Rose appearance on July 21.

On the July 18 interview, he described as “our best allies, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar,” and repeated that those regimes wanted to stamp out terrorism. “It’s a few out of the billion, 800 million Muslims.” America needs a Middle East policy that’s “firm and supportive,” he said.

After the interview, the indictment says, Barrack emailed Rashid Alshahhi, a UAE official who is also under U.S. indictment, “I nailed it ... for the home team.”

The Charlie Rose appearance followed on July 21. Rose was an ideal interviewer for Barrack. Accustomed to plying his guests not merely with softball questions but with what the writer James Wolcott once described in Vanity Fair as “verbal balls of yarn,” Rose absorbed Barrack’s depictions of Trump’s personality and policies with scarcely a hint of skepticism.

Barrack managed to slip an encomium to his alleged clients into the chat, mentioning as “allies ... countries like Abu Dhabi with Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed,” the emirate’s crown prince. Barrack also vouched for “Saudi Arabia with the young prince.”

(That was a reference to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who was subsequently identified by the CIA as having ordered the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a columnist for the Washington Post, in October 2018.)

The indictment says Alshahhi texted Grimes with the message, “the feedback is amazing.”

Barrack resurfaced on Bloomberg TV on Sept. 27, 2016, again giving a shout-out to the UAE leadership, “Sheikh Mohammed, Sheikh Takmoum.” (Barrack may have misspoken — he was probably referring to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai and prime minister of the UAE.) Barrack “is doing well,” an Emirates official told Alshahhi, who passed the good word on to Grimes.

Florida Gov. DeSantis is running a victory lap over his COVID-19 response as the press plays along.

The final interview in the sequence cited in the indictment aired on Bloomberg TV on Jan. 31, 2017. That was only days after Trump’s executive order restricting entry into the U.S. of residents of seven Arab countries, a step that provoked great consternation in the UAE.

Barrack tried to minimize the impact of Trump’s order by explaining that it was directed not at “good Islam” but at radical immigrants. He praised “the Imams in the good Mosques preaching and teaching and helping us to curate the refugees who are coming here.”

The indictment says Grimes sent a link to the interview to Alshahhi, who responded, “Wow, that’s exactly what I wanted.”

One might be tempted to defend this sedulous cultivation of Tom Barrack by Bloomberg and Charlie Rose by asserting that no one on the outside could know the truth of what was going on inside Trump’s brain or the Middle East at the time.

That won’t do. Tom Barrack snowed them, by projecting an earnestness and a cocksure confidence in his own knowingness that television finds irresistible. Having landed on Bloomberg once, he was on the bookers’ list for return appearances. In none of them was he ever confronted by a genuine expert in Middle East politics, someone who might have asked, “Why do you keep bringing up the Emirates? How could you link them to Saudi Arabia and Israel as though they all have the same political interests?” And perhaps most important, “What are your financial interests in that region?”

By the same token, Barrack was never confronted with a guest who might have a different view of Trump’s personality and management skills, developed through assiduous reporting rather than cronyism.

Shoe-leather reporting, however, is in decline on television (as it is in print). The gap has filled up with useless, vacuous swill of the sort that Tom Barrack dispensed in 2016 and 2017.

In fact, it’s worse than useless. Bloomberg and Charlie Rose allowed Barrack to put out an image of the Trump inner circle and a take on Middle East policy that worked profoundly against the public interest. We got a glimpse of that from the Barrack indictment, but it came years too late to matter.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.