Could the ‘Pittsburgh left’ help Argo AI win the self-driving car race?

To understand why it’s so hard to make a car that drives itself, pay attention to how people cross the street next time you travel. In Los Angeles, pedestrians wait for the walk sign. In San Francisco, some do, and some don’t. In Pittsburgh or Chicago, don’t expect a car to stop just because someone’s entering a crosswalk. In Palo Alto, sticking out a toe will often prompt an oncoming car to stop.

Different cities, different laws, different customs, different traffic patterns. The kaleidoscopic diversity on city streets across the U.S. and around the world is one reason self-driving cars are not quite yet ready for prime time. The real world is a complicated place for human drivers to find their way around. Robot cars are just getting started.

Yet the driverless technology company Argo AI thinks it’s on the verge of solving the complicated problem well enough to safely introduce a robotaxi service next year. To that end, it’s testing and training its sensors and software in seven different cities all at once, with an intense focus on well-mapped areas it calls “geonets.”

Ford and Volkswagen have invested nearly $4 billion in cash and intellectual property into the company. Ford intends to start deploying robotaxis in Ford cars equipped with Argo technology in partnership with an undisclosed ride-hailing service in 2022, likely in Miami or Austin, Texas, or both.

Bryan Salesky, Argo’s founder and chief executive, helped companies commercialize robot technology at Carnegie Mellon University. He also worked on Google’s driverless car program before Argo got started in 2016.

He understands that investors want to move to market as quickly as possible. There’s a lot of money on the line. Forecasts for the global driverless vehicle market have it being worth $60 billion or more a year by 2030.

Yet Salesky, 40, knows that too-rapid deployment could set the whole industry back, if the public thinks the technology isn’t safe.

“We want the self-driving system, given its perceivable environment, to be able to foresee the actions of other actors around our vehicles” to create “an envelope of safety around these objects,” Salesky said in a recent interview with The Times in Palo Alto.

John Casesa, who steered the Argo AI investment as Ford’s head of global strategy, translates Salesky’s engineering-speak this way: “Having machines run over people, that would be unpalatable.”

Casesa, now at Guggenheim Partners, said he’d watched Salesky in action and concluded he and co-founder Peter Rander were the team to midwife Ford’s driverless ambitions. “What I loved about Bryan is that he has humility about this,” Casesa said. “It’s very hard to predict the future. We agreed we can make automobiles intelligent and autonomous … but safety clearly takes precedence over time to market.”

So far, only one company had deployed a truly driverless robotaxi service in the U.S. That’s Waymo, the Google offshoot, which in 2019 began running the service on the relatively predictable streets in the suburbs of Phoenix. (Relatively but not entirely. Uber’s self-driving car project stumbled after one of its robocars killed a pedestrian in 2018 as she walked her bicycle across a four-lane road in Tempe. The test driver was not paying attention. Uber has since sold its self-driving unit.)

Waymo has yet to announce any expansion plans, although it has begun testing driverless cars in San Francisco. General Motors Co’s Cruise and Amazon.com Inc.’s Zoox are testing there as well. Cruise hints it may deploy in San Francisco next year and Dubai after that.

No one is rigorously testing in as many cities as Argo, which is based in Pittsburgh with a major research and development center in Palo Alto. Its test cars are running, with two trained test drivers aboard each vehicle, in Miami, Austin, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Palo Alto and Washington, as well as in Munich, Germany. (Waymo said it has “driven” its test vehicles in 25 cities.)

The cities are diverse enough to provide a solid base of knowledge about dense urban areas that can eventually be applied to cities around the world — not only about laws, geography, weather, signage, and traffic patterns, but also about human behavior.

Take Pittsburgh, which is known for the “Pittsburgh left.” That’s a maneuver wherein the driver of the first car in line at a stoplight signals to turn left. When the light turns green, the driver veers left immediately — making the turn before oncoming traffic goes straight. It’s technically illegal but widespread. A robot car must be aware of such local idiosyncrasies to harmonize with other traffic, Salesky said. If robot cars don’t demonstrate reasonably “naturalistic” driving skills, he said, they’ll make people mad.

“The whole industry is closing in on launching services in the next year or two,” said Sam Abuelsamid, a market and technology researcher at Guidehouse Insights. “One aspect that may set Argo and Ford apart is the multi-city approach.”

Developing robotaxis in dense urban areas is a lot tougher than programming cars to drive themselves on Interstate highways or in far-flung suburbs. But that’s where the taxi market is.

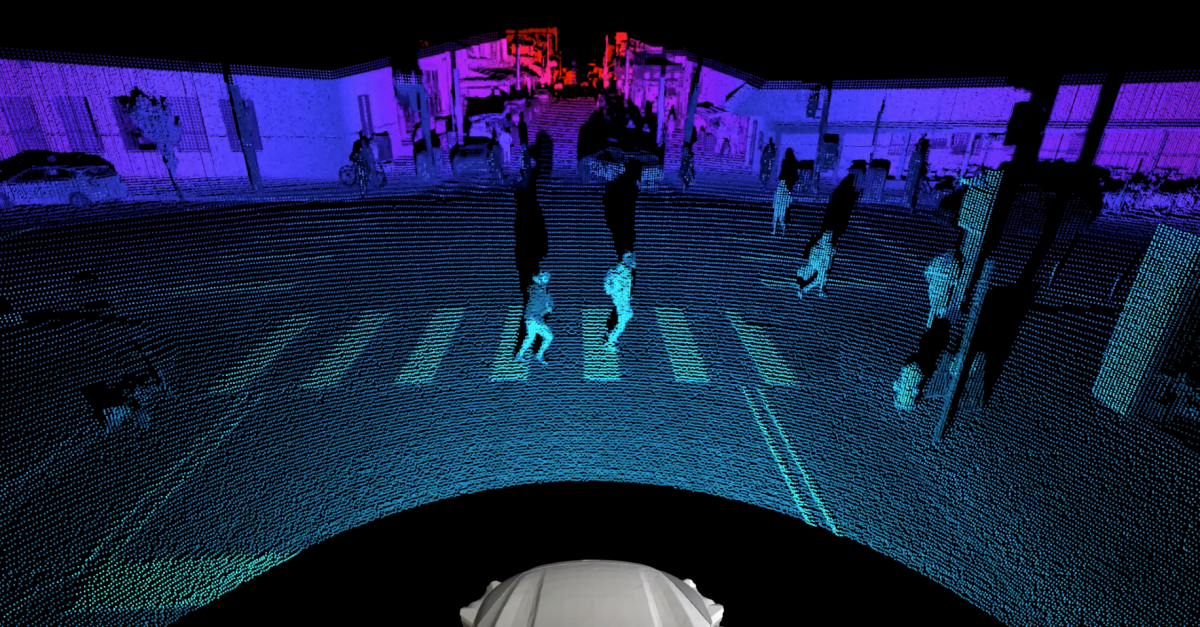

Training robotaxis involves a lot more than recognizing streets, traffic signs, cars and trucks. The vehicles must share the road with pedestrians, bicyclists, electric scooter riders, skateboards and more. Figuring out where each of them is, where they’re headed and what they might do next is a key safety problem for self-driving cars.

Nowhere is that problem more acute than in Miami’s South Beach, where hard-core party people and let-loose suburbanites make their way from hotel to restaurant to nightclub and back to the hotel again night after night.

Salesky said it’s the most unpredictable pedestrian environment of all Argo‘s initial cities, and the strength of its sensors and its prediction software will be key to success there.

The city rollouts will occur in Argo’s geonets, which determine where a robot can go and where it can’t. A geonet involves not physical barriers but a network of approved streets.

In South Beach, Argo plans to cast its geonet around specific roadways where robotaxi demand is highest, and make sure its artificial intelligence systems deeply understand them — not just where the street signs, traffic lights and road markings are, but local traffic laws and even local driving habits.

That sparse network would start out in a few square miles of a city and grow from there, as the robot cars prove themselves safe (or not) and as the cars get smarter. (Autonomous trucking is expected to go commercial over the next few years, too, with its own kind of geonet: Interstate highway driving, with transfer hubs at offramps.)

“In the future, we start to color the net in by adding additional roads,” Salesky said. “Over time, the geonet gets denser and denser. You can then end up supporting an entire region.”

As for whether that will happen in time for a 2022 launch, Salesky said Ford’s timeline is “reasonable,” but “I’ve always been clear about when it’s time to deploy a driverless service. It’s ready when it’s ready.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.