As the Trump era comes to an end, what happens to Big Tech?

In the days before the 2020 election was called for Joe Biden, President Trump was on Twitter — doing battle with Twitter.

As the incumbent tweeted through the slow vote-tallying process that would ultimately end in his loss, Twitter had covered much of Trump’s timeline with warning labels cautioning that the president’s posts contained disputed and potentially misleading information. Trump responded by tweeting a reference to Section 230, the obscure, decades-old law that shapes content moderation on social media.

Such feuds with Silicon Valley companies have been a through-line of Trump’s presidency; he has often criticized Facebook and Twitter for conspiring against him, siding with liberals and stifling conservative voices, even as Facebook helped get him elected and Twitter remained his soapbox of choice.

He has blasted Amazon and spearheaded a resurgence of Big Tech trust-busting that found purchase among Republican congresspeople, red state attorneys general and his own Justice Department.

His focus on tech also bled into his long-running trade war with China, as he issued executive orders to keep Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei out of America and ban the Chinese-owned apps WeChat and TikTok (unsuccessfully so far, in the case of both apps).

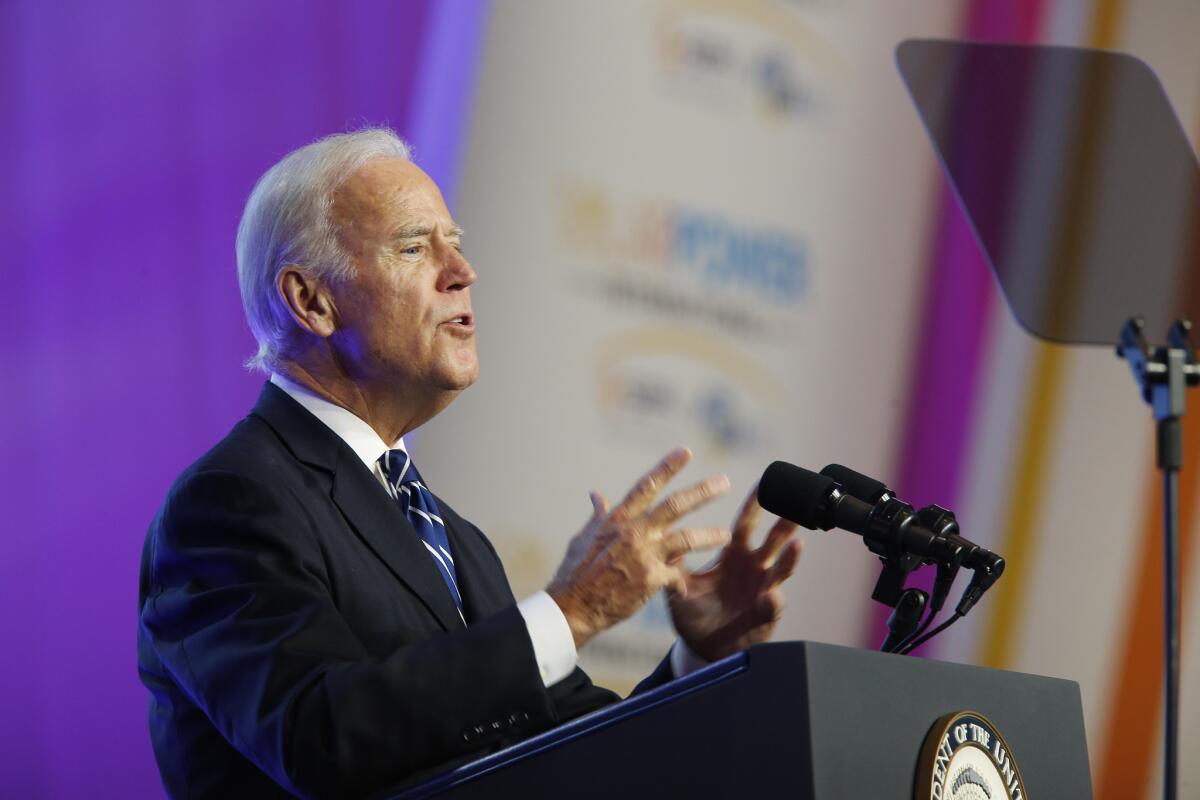

Now, as Trump enters his lame duck period and Biden readies for the transition of power, there is opportunity for change — but how much can actually be expected?

The paradigm that comes next is not entirely clear. Aside from calls for the social media giants to more aggressively fight misinformation, Joe Biden did not make Big Tech a major focus of his campaign. The makeup of Biden’s Cabinet remains uncertain as well.

“My sense is that the Biden team hasn’t developed detailed positions on some of the most urgent questions relating to big tech,” Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said in an email.

It’s possible that the transition to a Biden presidency would not be as transformative for the tech world as it would be for other sectors. Tech reform has been the site of some unlikely bipartisanship during the Trump years, with the confluence of progressive regulation efforts and conservative free speech concerns yielding an unlikely alliance against Big Tech that could continue under a President Biden.

Even if the election ends with a split government — Biden in the White House but Mitch McConnell controlling a still-red Senate, potentially resuming the obstructionist strategy he honed during the Obama years — it’s therefore not inconceivable that Biden could rein in the Silicon Valley giants at least slightly.

On antitrust, for instance, there’s clear overlap between progressive calls to “break up Big Tech” — which Biden has nodded to but not endorsed — and the various tech antitrust investigations Trump has overseen. Christopher Lewis, president of internet advocacy nonprofit Public Knowledge, pointed to the House antitrust subcommittee’s recent investigation into anti-competitive practices in the sector as indicating a possible path forward.

“It was a bipartisan investigation, and … there were a lot of bipartisan and shared findings,” Lewis said. “There’s room for legislative work based off of that investigation, that one still hopes can have a bipartisan effort. So that’ll be a big priority.”

Even if Republicans resume a more traditional hands-off approach to industrial consolidation, a Biden administration could act on its own to regulate mergers and acquisitions, said Gigi Sohn, a distinguished fellow at the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law and Policy. “They can be more active antitrust enforcers [and] more skeptical of both vertical and horizontal mergers,” Sohn explained. “I expect them to be more like the Obama administration, which didn’t allow T-Mobile and Sprint to merge, didn’t allow Time Warner and Comcast to merge.”

Social media content moderation represents another potential site of compromise. Democrats generally want more moderation thanks to concerns about viral disinformation and foreign election meddling, while many Republicans want less due to concerns that conservative voices get “silenced” online.

But both sides have taken issue with Section 230, the law that drew Trump’s ire as the ballots were coming in. In one of the election’s few areas of explicit agreement, Biden and President Trump have both called for the law to change, with Biden at one point telling the New York Times that “Section 230 should be revoked … for [Facebook CEO Mark] Zuckerberg and other platforms.”

Jaffer speculated that Biden’s stance is more nuanced: “I assume what he really means is that he wants to replace the rule of near-categorical immunity with something more fact-sensitive.”

“That’s a reasonable idea,” Jaffer added, “but the details will matter.” And the shared enemy that brought Democrats and Republicans partway together during the Senate’s recent Section 230 hearing could evaporate quickly once those details come to light.

Social media executives seem to be anticipating some sort of crackdown. In the lead-up to the election, amid polling suggesting a Biden sweep, Facebook became more aggressive in its moderation policies, banning Holocaust denial in a reversal of a long-running policy, and reducing the spread of a New York Post story alleging corruption by the Biden family.

Some have speculated that Zuckerberg’s change of heart came in anticipation of a Biden win, pre-empting future calls for more stringent moderation; although even before Biden was the Democratic front-runner, the Facebook CEO had begun pivoting from lobbying against regulations to calling for more of them. Facebook and Zuckerberg have attributed the policy changes to growing concerns about hate-based violence and electoral misinformation.

On Chinese tech — which prompted Trump’s attempts to ban Huawei, WeChat and TikTok — Biden hasn’t substantially distinguished himself from Trumpism. Trump has often framed economically ascendant China as a threat to both U.S. trade and national security, as well as blaming it for the spread of the coronavirus; but Biden’s campaign consistently tried to cast itself as harder on China than Trump, not softer.

In September, Biden deemed TikTok “a matter of genuine concern,” echoing Trump’s framing of the attempted ban.

One topic that’s become increasingly urgent in the era of telework and Zoom-schooling is the “digital divide,” or disparities in who has access to the internet. Biden’s campaign has pledged to expand “broadband, or wireless broadband via 5G, to every American,” bringing internet access to rural areas, urban schools and tribal lands, including with a $20-billion investment in rural broadband.

“I think there’s … some bipartisan opportunities there, just because everyone has been impacted by it and some of the hardest-hit communities are rural communities, red parts of states,” Lewis noted.

On other topics, a partisan shift can be expected. For instance, Biden has said he’ll lift Trump’s suspension of H1-B visas, which allow companies to hire foreign workers with specialized skills — about three-quarters of which go to tech workers.

In this regard, a move away from Trump’s protectionist efforts positions Biden as a more natural ally of Silicon Valley — echoing the Obama years, under which Democrats and tech leaders enjoyed a generally friendly relationship. Many tech executives were anti-Trump in 2016 , and tech employees disproportionately donated to the Biden campaign this cycle.

Markets expressed confidence that a Biden presidency — especially one constrained by a Republican Senate — wouldn’t bring an end to the runaway growth that tech companies have experienced despite the Trump administration’s antagonism. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index closed an uncertain election week up 7.3%, fueled in part by gains from some of Silicon Valley’s largest players.

Some policy areas have simply not been fleshed out by Biden enough to know if and how they’d change.

Domestic surveillance was a major concern when Biden was vice president; stories like Edward Snowden’s NSA whistle-blowing and the FBI’s fight to make Apple unlock the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone remain hallmarks of the Obama administration’s relationship with tech.

Biden’s campaign has only nodded to the issue, calling for tech and social media companies to “make concrete pledges for how they can ensure their algorithms and platforms are not empowering the surveillance state” — as well as not facilitating Chinese repression, spreading hate or promoting violence. In his New York Times interview, he said America “should be setting standards not unlike the Europeans are doing relative to privacy.”

Biden did not focus on automation to the extent of primary challengers such as Andrew Yang and Bernie Sanders . However, his website does say he “does not accept the defeatist view that the forces of automation and globalization render [America] helpless to retain well-paid union jobs and create more of them,” and he calls for basic employee protections around automation and a $300-billion investment in artificial intelligence R&D (as well as electric vehicles and 5G networks).

One area around which the tenor of discussion will almost certainly shift is the role social media platforms should play in moderating misinformation, especially if it comes from the president’s account. But that doesn’t mean the issue of “fake news” will go away, either.

“Misinformation,” cautioned Lewis, “is bigger than just Donald Trump.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.