Column: Trump claims the economy will do better if he’s reelected. History says he’s wrong

Until very recently, Donald Trump was fond of proclaiming that his reelection would be a boon to the U.S. economy and the stock market.

If Democrat Joe Biden were to be elected president, he told Maria Bartiromo of Fox Business Network, “this market’s going to crash” and Biden would “tax this country into a depression like in 1929.”

If this sounds like typical Trumpian bluster, it also feeds into the received wisdom that Republicans are pro-business and Democrats the opposite, and therefore the economy and markets do better under the the GOP.

The U.S. economy performs much better when a Democrat is president than when a Republican is.

— Alan Blinder and Mark Watson, Princeton University (2016)

As is often the case, the received wisdom is wrong. Both economic growth and stock market gains have been stronger under Democrats than Republicans, according to measurements dating back to Herbert Hoover.

For some reason, this fact escapes many political analysts when they ply their trade during presidential election years.

The empirical truth, “while hardly a secret, is not nearly as widely known as it should be,” economists Alan S. Blinder and Mark W. Watson of Princeton wrote in 2016, in the most thorough analysis of the trends. “The U.S. economy performs much better when a Democrat is president than when a Republican is.”

Blinder and Watson found that the Democratic-Republican gap was “nearly ubiquitous” — it remained detectable no matter how economic growth was defined, and was so “startlingly large” that it “strains credulity.”

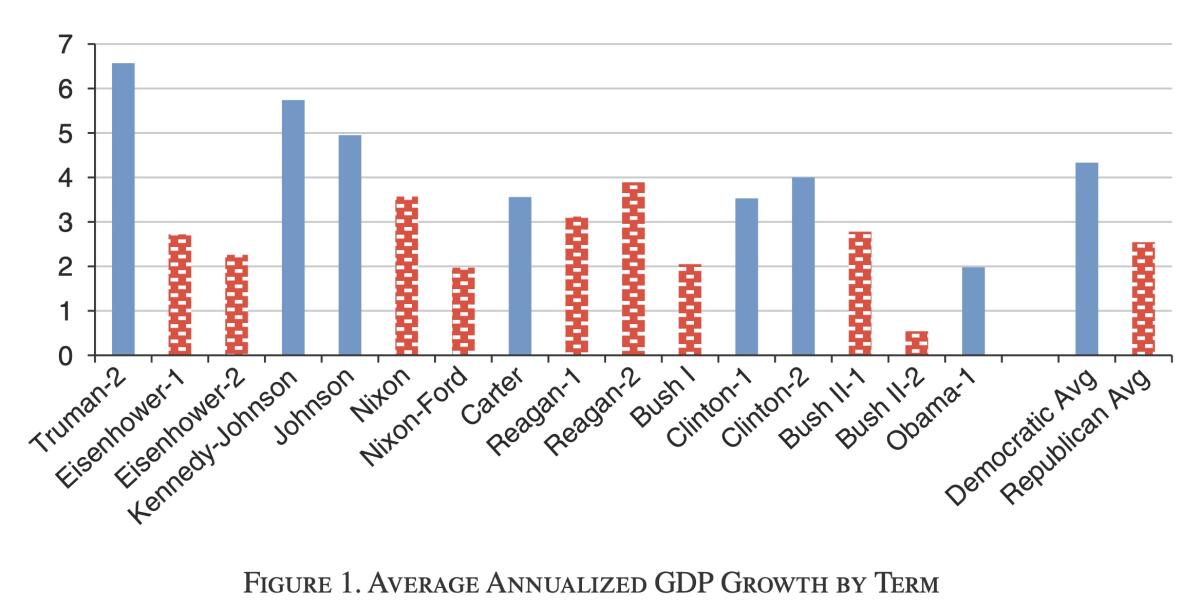

But there it is: Annualized growth in gross domestic product was 1.8 percentage points better under Democrats than Republicans over 16 complete presidential terms from Harry S Truman through Obama. That was a large enough time span for the difference to be statistically significant, Blinder and Watson judged.

The gap was reflected in more than GDP: “Democrats do better on almost every criterion,” Blinder and Watson wrote. Business investment was greater under Democratic administrations, as was consumer spending.

Trump’s economic vision looks to a long-gone America; Biden’s to the next stage.

Blinder and Watson couldn’t quite put their fingers on all the reasons for the performance discrepancy. They noted that expansionary spending for the Korean War, which began under Democrat Truman and ended under Republican Eisenhower, explains part of the gap, but only a small portion.

On the other side of the ledger, they noted, “Reagan initiated a huge military buildup in peacetime, and both Bushes were wartime presidents.”

Oil and productivity shocks, defense spending, consumer expectations and international economic growth, could explain as much as 70% of the gap. But actual White House policy didn’t seem to matter.

“Our empirical analysis does not attribute any of the partisan growth gap to fiscal or monetary policy,” Blinder and Watson wrote. (Emphasis theirs.) Curiously, the performance gap is associated with the party occupying the White House, not with the makeup of Congress.

“The rest remains, for now, a mystery of the still mostly unexplored continent.”

Let’s delve deeper.

First, economic growth. According to conservative political scientist Jeffrey H. Anderson writing for the Hudson Institute in 2016, four of the six postwar presidents who experienced average annual inflation-adjusted GDP growth better than the postwar average of 2.9% were Democrats.

The list was led by Lyndon Johnson with 5.3% a year, followed by Kennedy, Clinton, Reagan, Carter and Eisenhower, in that order.

Of the six with worse annualized growth than the average, four were Republicans. The list starts with Nixon at 2.8% annualized, followed by Ford, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Truman and Obama (through 2015), in that order.

Truman’s average, Anderson acknowledged, was held down by the economic contraction immediately following the war, though recovery was strong in his final years — his 8.7% expansion in 1950 was the best one-year performance of any postwar president.

Defenders of the Republican record might point out that GOP administrations suffered three elemental economic meltdowns starting in 1929: the great crash and three Depression years following the crash, the Great Recession starting in 2008 and the pandemic of 2020.

That’s true, but it misses the point. The GOP record isn’t the consequence of those events themselves, but of the Republican failures to address them. That may be the defining difference between Democrat and Republican approaches to managing the economy.

A new New Deal would correct America’s 50-year decline and fix the COVID-19 pandemic, too.

Hoover, for instance, could have taken the same steps that Franklin Roosevelt did to respond to the Depression, including disconnecting the U.S. economy from the gold standard, and pumping money into household budgets through jobs and public works projects.

Hoover was hamstrung, however, by his devotion to Republican economic orthodoxy, which was based on keeping government hands out of economic management.

As Henry Morgenthau, FDR’s second Treasury secretary, observed, Hoover stuck with the gold standard in the first years of the slump even after it was abandoned by Britain and France “evidently under the impression that that was a proud achievement, when it was obviously economic suicide.”

George W. Bush left it to his successor, Barack Obama, to craft a fiscal response to the 2008 crash. Obama negotiated the $787-billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in the first month of his term in 2009, jump-starting the recovery — though it was smaller than many economists advocated, largely because of the refusal of the Congressional GOP to make it larger.

The final reckoning of the COVID-19 pandemic has yet to be written, but Trump has replicated the approaches of his GOP predecessors by taking virtually no significant steps to respond.

That may well be seen, in the final analysis, as having heightened the toll of deaths and sickness and prolonged the economic consequences. Thus far, the pandemic has wiped out all the job and income gains seen in the first three years of Trump’s tenure, and then some.

Trump’s record hasn’t factored into most analyses of economic growth because the full story hasn’t yet shown up on government statistics. What can be said thus far, however, is that despite Trump’s claims of having overseen a uniquely powerful economic expansion, that simply isn’t true.

In many respects, his first three years pale in comparison to Obama’s last three years. The economy added 1.68 million more jobs in the latter period than in Trump’s first three years, according to calculations by the Project to Raise America’s Pay, which is devoted to alleviating wage stagnation.

Then there’s the stock market. Trump has consistently tried to take credit for a rise in the market during his administration: “The reason our stock market is so successful is because of me,” he claimed in November 2017, his 11th month in office.

Despite Trump’s claims, prescription drug prices are still rising.

The claim hasn’t aged well. From Trump’s inauguration in January 2017 through the end of 2019, the annualized return of the Standard & Poor’s 500 index was 15.18%. In the last three years of Obama’s administration, it was 8.87%, but across Obama’s eight years in office, the average annualized return was 14.49%.

Returns in 2020 appear poised to lower Trump’s average; as of Monday’s close, the S&P 500 has returned 3.73% for the year to date.

What Trump can say is that his record so far is better than that of Republican presidents dating back to Hoover. The average annualized return of the S&P 500 since Hoover’s inauguration year of 1929 has been 1.71% under Republican presidents, but 10.83% under Democrats. The most notable difference here is between Hoover, who presided over a negative 30.82% annualized return during his term, and FDR, who notched a positive 33.28% annual return in his first term.

Yet the gap seems to persist even when the Great Depression and recovery are removed from the calculations. Blinder and Watson, whose database starts with Truman, found that annualized S&P 500 returns were 8.35% when a Democrat occupied the White House and 2.70% when it was a Republican. They didn’t regard the gap of 5.65 percentage points as statistically significant, however, due to the inherent volatility of stock prices.

So where does that leave our crystal ball? The one element underlying economic growth that gets short shrift in most of these analyses is government investment. In general, Republican administrations have been focused on cutting taxes, which places boundaries on investment. There are exceptions, of course: Republican Dwight Eisenhower launched the interstate highway system and Hoover started the construction of the dam on the Colorado River that would bear his name.

But the GOP has typically been loath to pay for infrastructure construction and tends to start agitating for cutbacks in government spending as soon as the first glimmers of success appear — as they did during the New Deal and Great Recession, and as they’re doing now, when they’ve resisted negotiating for a fourth coronavirus rescue package.

Tax cuts, by their nature, are narrowly based. That was the record of Reagan’s tax cuts and the 2017 cuts engineered by Trump and a Republican congress. Expanding the government’s role in the economy, especially during slumps, tend to have broader effect. Public works projects put people to work in the short term and provide the bedrock of economic expansion for decades to come. Maybe that’s the secret of Democratic success.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.