Column: Why can’t Twitter and Facebook hold back the torrent of right-wing conspiracy claims?

By conventional standards, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube showed themselves to be paragons of public service Monday when they took down a video promoting a long-debunked “cure for COVID” and agitating against mask-wearing.

The conservative broadcast chain Sinclair also has been praised in some quarters for canceling a segment on one of its television shows promoting an especially unhinged assertion that Dr. Anthony Fauci played a role in manufacturing coronaviruses and sending them to China.

By real-world standards, however, the social media giants and Sinclair failed miserably.

We’re a supporter of free speech and a marketplace of ideas and viewpoints, even if incredibly controversial.

— Sinclair Broadcast Group

The video remained up on Facebook for hours, long enough to garner more than 14 million views, and reportedly can still be found by determined searchers. Twitter not only deleted the video, but also restricted the account of Donald Trump Jr., who had posted the video on his account. The suspension was to last only 12 hours, however.

And Sinclair came close to providing a platform to the claim about Fauci embodied in a video documentary titled “Plandemic.”

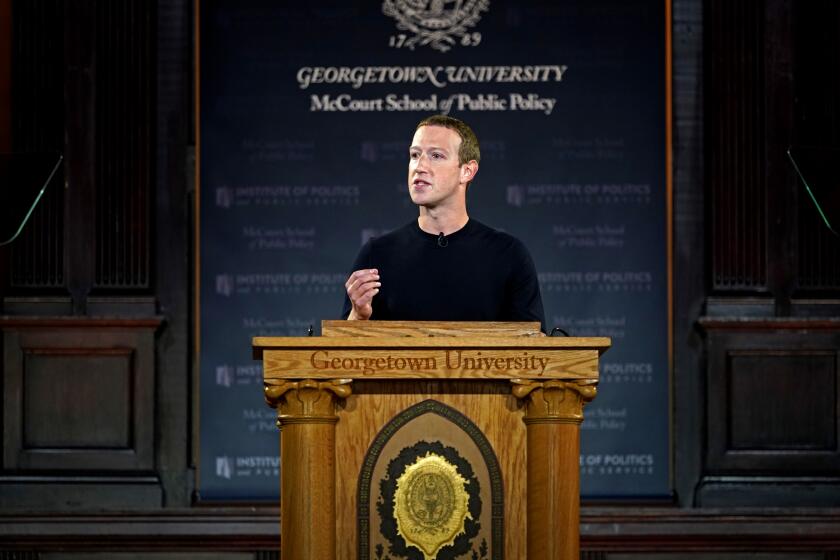

Concerns about the firms’ inability — or unwillingness — to police their platforms for manifestly deceptive misinformation and disinformation may surface Wednesday during a joint appearance before the House Judiciary Committee by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Apple Chairman Tim Cook and Sundar Pichai, the CEO of Alphabet, which owns Google and YouTube.

The session’s nominal topic is the market power accumulated by these giant corporations, but the power of social media platforms to distribute dangerous myths is certainly pertinent.

It’s long past time for Facebook to take complaints about hate speech and misinformation as more than occasions for navel-gazing.

Indeed, Darrell M. West of the Brookings Institution suggested that one of the questions that should be high on the lawmakers’ agenda is: “What have you done to stop the use of your products for racist appeals, hateful actions, or false information?”

It’s fair to say that inoculating these platforms against informational toxins isn’t always a simple matter, in part because distinguishing the purveying of disinformation from legitimate differences of opinion, especially on scientific matters, isn’t always easy.

Some of the conspiracy theories that leach into social media come cloaked with the aura of government statements, thus providing a convenient defense against calls to remove the material.

Consider the case of President Trump, whose Twitter output is not only voluminous — more than 50 tweets on Monday alone — but also chockablock with tweeted and retweeted conspiracy claims and false assertions. The Washington press event at the center of the controversial video Monday was fronted by Rep. Ralph Norman, a far-right member of the South Carolina Republican delegation.

As we’ve reported, the ability of misinformation and conspiracy-mongering to infect our public discourse is greater than ever before because its sources are no longer limited to inhabitants of the lunatic fringe or commercial entities that have profited from misleading the public, such as tobacco companies.

The speed with which this material can reach the public makes a mockery of the old saw about how a lie can get halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on — today, a lie can metastasize throughout the global body politic before the truth can even get out of bed.

Scientists are using the coronavirus to study the contagion of misinformation

The defense for posting and publishing such noxious material long has been that exposing it to the public has a disinfectant effect — the public will be able to weigh it against truth and serious discourse, and it will wither away as a result. The power of social media to give such material credibility merely by making it public points to the question of whether some viewpoints are just too noxious.

There should be no question that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and their cousins could be much better at blocking some of this material before it can reach millions of viewers.

For one thing, some of it has long since been established as mendacious or deceptive.

Let’s consider the video involved in Monday’s controversy. Originally posted by the right-wing Breitbart News, the video featured a group of white-coated doctors associated with organizations calling themselves America’s Frontline Doctors and the Assn. of American Physicians and Surgeons.

Neither of these organizations nor many of the participants are unknown to followers of conspiracy theories or debunkers of pseudoscience.

The head of America’s Frontline Doctors, Simone Gold, an emergency room physician, has described advice to wear masks as “a con of massive proportion.” She says the media has “an agenda ... to make you think that there’s no actual facts out there that you can discern for yourself. ... That’s a really good way to let people live in fear.”

Gold, by the way, was a member of the so-called “expert panel” assembled by the Orange County Board of Education as window-dressing for its “white paper” advocating irresponsibly that schools in the county reopen for class without masks or social distancing.

The thrust of the video was to promote the use of the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19.

The persistence of the claim for this nostrum, which has been incessantly talked up by President Trump, is simply astonishing given that every randomized clinical trial of the treatment, the gold standard in clinical studies, has found it to be ineffective against the virus (and hazardous for some patients besides).

Yet the videotaped event featured Stella Immanuel, a Houston physician who claims to have treated more than 350 patients with hydroxychloroquine and “they’re all well.” She called the studies debunking the drug’s effectiveness “fake science” and said, “You don’t need masks; there is a cure.”

Immanuel maintains on her website that “serious gynecological problems, Marital distress, miscarriages, impotence, untold hardship, financial failure and general failure” are caused by “evil spiritual marriages.” After Facebook took down Monday’s video, she issued a sort of curse against the company via Twitter: “Put back my profile page and videos up or your computers will start crashing till you do.”

Facebook, Twitter and YouTube would have us believe that they were caught flatfooted for hours by this material.

Then there’s Sinclair, which played a more active role in distributing patent disinformation than the social media platforms, until public disclosure caused it to backtrack.

Sinclair is a rapidly expanding broadcast conglomerate that now operates more than 190 television stations coast-to-coast. The right-wing tenor of its news content suggests that it’s hoping to share the conservative market with Fox, if not surpass its rival.

Over the weekend, Sinclair was prepared to give a platform to a participant in a certain video known as “Plandemic.” Clips of the video don’t seem to be available as of this writing from the production’s website, but as pseudoscience debunker Dennis Gorski reported in May, the blurb for the video included statements such as this:

Mark Zuckerberg’s cluelessness shows how socially dangerous Facebook has become.

“The media has generated so much confusion and fear that people are begging for salvation in a syringe. Billionaire patent owners are pushing for globally mandated vaccines. Anyone who refuses to be injected with experimental poisons will be prohibited from travel, education and work. No, this is not a synopsis for a new horror movie. This is our current reality.”

The participant was Judy Mikovits, who was to be featured in a segment of Sinclair’s show “America This Week,” interviewed by host Eric Bolling, a former Fox News host. Mikovits’ professional career was subjected to scrutiny earlier this year by Science Magazine, which did not paint a pretty picture.

In the Sinclair segment, according to a clip and a transcript published by Media Matters for America, Mikovits states, “I believe Dr. Fauci has manufactured the coronaviruses in monkey cell lines and shipped them from and paid for and shipped the cell lines to Wuhan, China, now for at least since 2014.”

Bolling subsequently brought on a guest who disputed the claim that Fauci was involved in manufacturing the novel coronavirus, though she maintained that the virus was likely made in a laboratory (another highly dubious assertion).

Sinclair at first defended its program. “We’re a supporter of free speech and a marketplace of ideas and viewpoints, even if incredibly controversial.”

But that won’t do. The defense of pandering to ignorance in the name of informational “balance” is an old stunt that depends on portraying disagreements as “controversies” even when no real controversy exists. (We took Katie Couric to task in 2013 when she aired an interview with an anti-vaccination activist as though she was merely reporting the controversy, and she quite properly conceded the misstep.)

In the Sinclair case, there is no controversy about Fauci’s role in the coronavirus. No serious evidence that he played any such role exists. Sinclair at first responded to “feedback” about the Bolling segment by delaying the broadcast but subsequently pulled the plug entirely, telling CNN that “given the nature of the theories [Mikovits] presented we believe it is not appropriate to air the interview.”

It’s gratifying, one supposes, that the limits of Sinclair’s shame and sensitivity to public “feedback” have been determined. But it was a close call. Sinclair should never have given a platform to Mikovits’ claim, for any effort to check it out would have revealed the dangers of putting it on the air. The question is whether Sinclair has learned anything from the episode — just as the question is whether Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have learned that it’s imperative to address videos such as the hydroxychloroquine news conference proactively. Lives are at stake.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.