Tesla’s insane stock price makes sense in a market gone mad

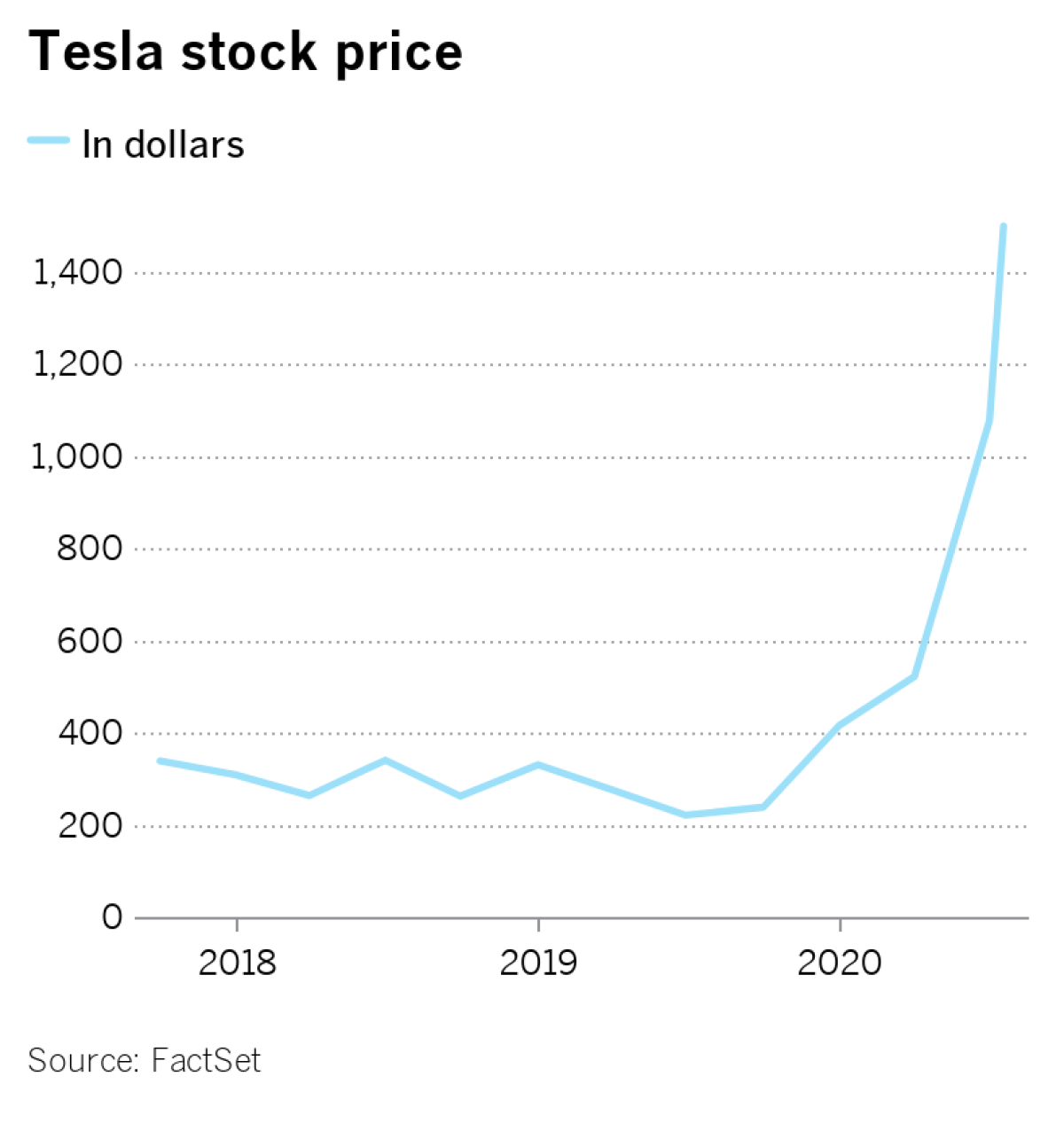

Like a SpaceX rocket lofting a Tesla Roadster into orbit, Tesla stock is on a vertical trip into outer space. Since March, the electric car maker’s share price has more than quadrupled to a mind-boggling market value of $290 billion.

That makes Tesla, which reported second-quarter earnings Wednesday, the world’s highest valued car company — if far from the largest. Of the 90 million cars sold around the world in 2019 Tesla sold 367,000. Take the two top-selling carmakers in the world, Toyota and Volkswagen, toss in Ford; the stock market still values Tesla higher than all three combined.

On Monday, Tesla stock climbed nearly 10%, adding $26.5 billion to its market value in a single day. It pulled back 4.5% on Tuesday, to $1,568.36 a share, then closed up about 1.5% Wednesday. Shares spiked more than 5% in after-hours trading when Tesla reported a net quarterly profit of $104 million.

Even Jim Cramer, the CNBC personality who has hyped Tesla stock plenty in the past, is astounded. Asked about Tesla stock on Twitter on Monday, he wrote: “I don’t even know if it is a stock. it is something else entirely, like a new species discovered in the wild.”

Or maybe it’s a more familiar beast, only supercharged. Tesla’s bewildering ascent makes more sense when you think of it as a hyper-exaggerated product of — and maybe metaphor for — a stock market that itself has stopped making sense, at least by conventional measures.

Hovering near record highs amid a global pandemic and economic catastrophe, the market, like Tesla, highlights the degree to which equity prices have come untethered from current economic reality and future earnings expectations.

In both cases, prices are supported by the infusion of trillions of dollars of new money into the economy and by the steady growth of passive investing, in which money automatically flows in from 401(k) contributions and is put to work buying stocks, pushing prices higher. The potential inclusion of Tesla in the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index adds upward pressure.

Then there’s the success of Chief Executive Elon Musk in crafting a beautiful-future narrative to explain why Tesla should be even more expensive than it is. Musk’s enormous compensation package is almost entirely tied to share price; on Tuesday, he qualified for an additional $2.1 billion worth of options after Tesla’s average market capitalization over a six-month period exceeded $150 billion.

Narrative aside, there’s little in the company’s recent performance to justify such outsize enthusiasm.

Although Tesla’s sales have grown steadily, there has been no sudden acceleration, and the company has repeatedly lowered prices. Tesla owes its string of small quarterly profits to government credits and aggressive booking of prepaid orders for a “Full Self Driving” technology that does not yet exist. Pay and bonuses — for workers, not for Musk — are being cut.

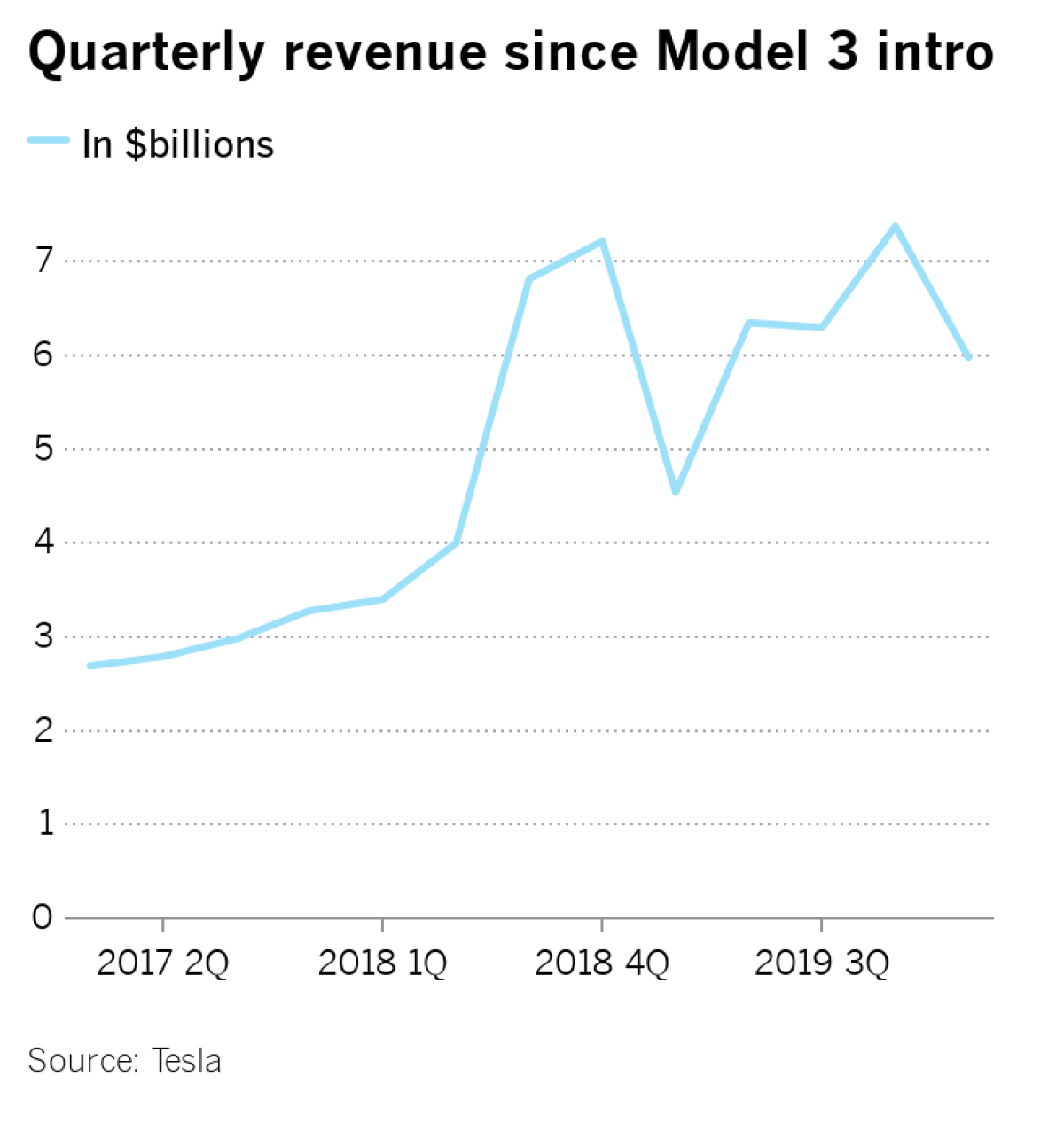

Overall, it’s hard to see Tesla, since it introduced the Model 3 in 2017, as a rapid growth company. (See chart.)

Tesla isn’t the only company whose rip-roaring market value is hard to square with the worst economy since the Great Depression.

In the classical analysis, stock prices indicate expectations of a company’s future profits. The cash can be used to reward shareholders through dividend payments or stock buybacks, or reinvested in the company to fuel future growth.

The profit outlook for 2020 looks bleak across the economy. The Wall Street Journal reports 180 companies in the S&P 500 have pulled their earnings guidance, which has led to “the widest dispersion in earnings estimates among analysts since at least 2007.”

Yet the S&P 500, after an alarming plunge in March, is headed again toward record highs. As Robert Kaplan, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, put it recently: “If you see that kind of disconnect, it doesn’t go on indefinitely.”

Several forces have pushed stocks high and kept them there even as 32 million people in the U.S. have applied for unemployment assistance since February and COVID-19 infections have surged.

One is the Federal Reserve Board, which has injected trillions into the economy to ensure liquidity, engorged its balance sheet with assets that normally would be traded in established markets, and created new dollars that could at some point spark inflation. It has even, for the first time, begun to buy junk bonds to help keep marginal companies and the hedge funds that invest in them afloat.

The Fed’s low interest rates have the effect of making equity markets about the only avenue for meaningful returns. Middle- and upper-class people used to retire expecting to live largely on interest thrown off by their investments in bonds. Not now.

Whether the Fed’s efforts put people back to work in large numbers is yet to be determined, but so far they’ve helped stock and bond markets defy gravity.

Fear of missing out on the bounces animates a new generation of day traders. The advent of no-fee retail investing apps such as Robinhood has invited new stock buyers, often young and inexperienced, into the mix. Compared with index funds, mutual funds, pension funds, and other huge institutional investors, individual stock traders don’t account for much market volume, but their bids can influence prices on the margins. Tesla is one of the most actively traded stocks on Robinhood, according to data compiled by robintrack.com.

At the same time, the steady rise of passive investing, in particular index funds that buy a broad cross section of stocks, has had a massive influence on the market’s long bull run. Offering a low cost entry point for risk-averse investors, passive investing has grown to account for 43% of U.S. shares by market capitalization, reckons Michael Green, partner and chief strategist at Logica Funds. Green, who previously worked as portfolio manager for investor Peter Thiel’s Macro fund, has researched passive investing with findings available to the public.

By purchasing stocks en masse in proportion to market cap, regardless of fundamentals, index funds and other passive investment vehicles have reversed the downward pressure traditional stock trading, informed by research and analysis, exerts on speculative securities, Green said. The more prevalent passive investing becomes, the more the market disconnects from the economic performance of companies. The growth of passive investment vehicles is increasingly a foregone conclusion because of regulations and demographics, Green said.

The danger, he said, is when investors get spooked and redeem their shares, index fund selling exceeds buying and the fund must sell stocks no matter how low the price goes. That, he said, could cause a severe market crash.

Passive investing may soon add more thrust to Tesla’s stock rocket in a more direct way. The company’s net profit of $104 million for the second quarter marks the first time in its 17 years it has achieved four profitable quarters in a row. Such a feat would qualify Tesla for a spot on the Standard & Poor’s 500 index. If S&P’s index committee approves its inclusion, index funds that track stock markets would be required to buy Tesla stock. A lot of it, potentially, because its massive current market capitalization would be reflected in its index weighting.

Yahoo’s inclusion in the S&P 500 in 1999 during the dot-com bubble boosted its stock 64% in the five days from its qualification to its official inclusion, to a then-impressive market value of $56 billion.

Inclusion, however, “is not automatic,” said Adriana Robertson, finance and law professor at the University of Toronto Law School. The S&P’s index committee “can decide whenever they want.” There’s no deadline to decide. And a March announcement by the index committee indicates no rush: it put regular index rebalancing on hold until further notice.

With the cost of making batteries stubbornly high, Tesla has relied on stock and bond markets, along with government subsidies, to keep afloat. The company earned a $16-million profit in the first quarter this year selling zero emission air pollution credits to other automakers. Musk cut worker pay and bonuses in this year’s second quarter, which will also help profits.

Unable to count on making money from selling cars, Musk has relied on other strands to weave his growth narrative. Last year he predicted Tesla would have 1 million driverless robotaxis on the road by the end of 2020. Autonomous car experts were, to be kind, skeptical. With six months to go Musk has stopped tweeting about it.

In 2017, he said Tesla would begin producing electric semi-trucks in 2019. Thus far there is no factory, and beyond a couple of prototypes, there are no trucks. Four years ago, he introduced a product called a solar roof — solar cells integrated into attractive roof tiles to generate electricity for the home. In July 2019, he tweeted Tesla was “spooling up production rapidly” to manufacture 1,000 roofs a week by the end of 2019. Apart from some prototype sites, a commercial product business does not exist, and the government-subsidized Buffalo, N.Y., factory where the roofs are supposed to be made has yet to spool.

Early this month, he said, “we will have the basic functionality” for driverless cars that can roam on their own anywhere in the world — by the end of this year. He did not define “basic functionality.”

No industry expert outside Tesla has expressed a belief the company is anywhere close to deploying driverless cars. In fact, a court in Munich, Germany, this month ruled Tesla misleads customers into believing the company’s Autopilot driver-assist technology is more capable than in fact it is. The court banned Tesla from including “full potential for self autonomous driving” and “Autopilot inclusive” in its German advertising. Korea officials are reportedly considering a similar move.

Musk’s unfulfilled claims about Tesla are part of a broader pattern. Another Musk company, Neuralink, is developing computer chips to be implanted in human brains. Musk has said the chip will “solve” brain and spine injuries, and “address epilepsy,” too, in the “near term.” He’s released no data to support such claims, which remain theoretical. Publicly announced plans to build networks of transportation tunnels through Musk’s Boring Co. in Chicago, the Northeast Corridor and elsewhere have been abandoned. Boring Co. is finishing a project that will provide paid rides in Tesla cars through a 4,500-foot tunnel near the Las Vegas Strip.

Although Tesla did not comment for this story, Musk’s legions of true believers have an answer for all this. Tesla is no mere car brand, they say, but a Silicon Valley-style technology company that is eons ahead of traditional carmakers in software development. Tesla did pioneer “over the air” software to upgrade the car and its systems remotely, while others are still playing catch-up.

One thing Tesla does have going for it is a constellation of commentators willing to sing its praises to infinity and beyond, though their convictions can appear shallow. Cathie Wood, chief executive of Ark Invest, regularly appears on CNBC to tell viewers Tesla stock will be worth $6,000 in five years. On July 1, Wood tweeted Tesla owners at some point in the future will each earn $10,000 in free cash flow every year by including their cars in a Tesla robotaxi network. But meantime, Ark regularly sells big chunks of Tesla shares. It sold nearly 140,000 Tesla shares the first two weeks of July alone even as Wood touted the company. Ark did not respond to a request for an interview.

The question of Tesla’s proper valuation divides analysts, but those whose firms tend to underwrite Tesla’s stock issues and bond offerings are the most supportive.

Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Jonas puts out investor notes with titles such as “Tesla and the Power of Hope.” He thinks at the current price the stock is overvalued but also puts a “bull case” price on the stock over $2,000.

“I don’t think of sell-side analysts as independent,” said Francine McKenna, a writer trained in finance who writes the accounting and audit online newsletter theDig.com. “Jonas is always making positive calls before Morgan Stanley helps Tesla raise money.”

Responding for Jonas, Morgan Stanley said he was “underweight Tesla” at the current price.

To be fair, it’s hard for Jonas or any stock analyst or investor to know what anything is really worth right now. When faced with facts that don’t add up, in a market in which the laws of economic physics no longer apply, the best you can do — as Musk has shown — is tell a compelling story.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.