Column: An apocalyptic collapse in state and local government employment is already upon us

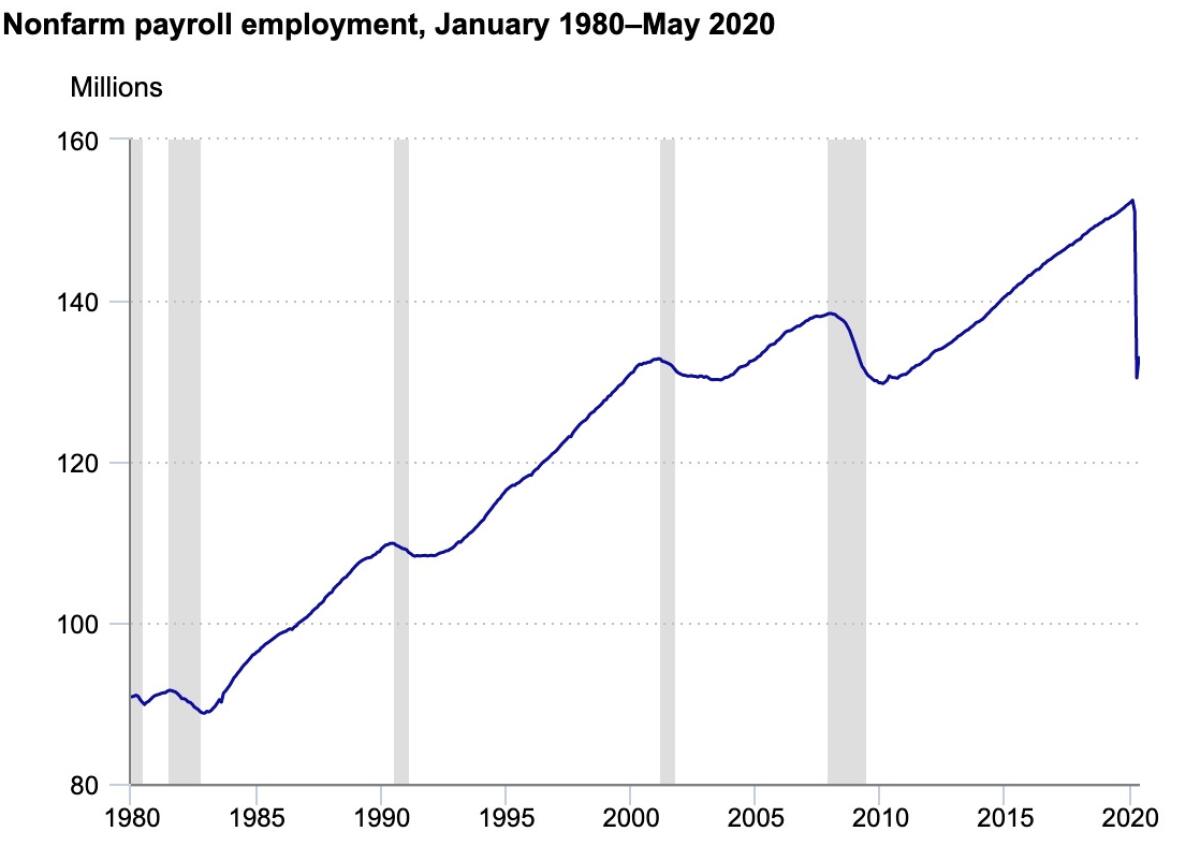

There were several reasons why President Trump should have held off from the self-congratulation last week after government figures showed an unexpected increase of 2.5 million jobs in May.

One was that the increase was barely a blip in the big picture. More than 22 million jobs had been lost in March and April, largely due to the coronavirus lockdown; that’s more than 14% of all nonfarm jobs that were in existence as of the end of February.

But the most important reason not to celebrate was hidden in the government report in plain sight. Employment by state and local governments has fallen off a cliff.

No state will escape the financial black hole created by this crisis.

— Mark Zandi, Moody’s Analytics

The employment report issued June 5 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that state and local government employment fell by 571,000 jobs in May. The month before, the loss was 964,000, for a two-month total of 1.535 million public sector jobs lost.

And the disaster may just be starting. Estimates of the size of the deficits faced by state and local governments through 2022 from the combination of heightened public health spending to combat the coronavirus and sinking revenues due to the economic shutdown and its continuing reverberations range from a catastrophic $500 billion through fiscal 2022 to a cataclysmic $959 billion through the end of next year.

(The first estimate is offered by Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics; the second by Timothy J. Bartik of the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.)

“No state will escape the financial black hole created by this crisis,” Zandi told CNN last month.

Some states, such as Texas and Oklahoma, suffered especially acutely because of the fall in oil prices, which help shore up their economies. But every state will have to confront a shortfall in personal income taxes stemming from layoffs and furloughs, and in sales taxes because people couldn’t leave their homes to shop in stores, go to restaurants and stay in hotels.

Rightwingers are using the pandemic to attack public workers, again

The situation demands congressional action. “They’re facing massive shortfalls, and there are not too many ways they can make that up,” economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research told me. “Their money mostly goes to hiring people. If Congress doesn’t come through with a big pile of money, they’re going to be hit really hard.”

He’s right. Unlike the federal government, states and localities can’t print money to paper over deficits. They’re generally required to maintain balanced budgets, so when deficits strike, their only option is to cut payrolls.

The relationship between state and local government fiscal health and the national economy is symbiotic. As a rule of thumb, every percentage point increase in the national unemployment rate costs state budgets about $45 billion, according to the Brookings Institution.

(The drop in the unemployment rate to 13.3% from 14.7% that the BLS reported on June 5 was based on a “misclassification” of temporarily furloughed workers as employed, when they should have been classified as temporarily unemployed. Factoring out that glitch, the unemployment rate was 16.3%.)

Looking at things from the opposite direction, history tells us that state and local government hiring is a key to keeping the current recession from turning into a depression.

The best evidence for how strapped state and local governments can become drags on growth comes from the 2008-09 recession, when they became relentlessly austere “anti-stimulus machines,” observes Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute.

If state and local spending had matched the trajectory it followed during the recovery from the recession of the early 1980s, “pre-recession unemployment rates could have been achieved by early 2013 rather than 2017,” Bivens calculates. “In short, this austerity delayed recovery by over four years.”

Closing the revenue gap with federal aid will save as many as 6 million jobs by the end of 2021, Bivens adds, placing the U.S. back on the path to full employment it enjoyed before the coronavirus pandemic.

Officials are ‘exploring’ a plan that allows workers to get up to $10,000, but requires them to pay back funds by deferring Social Security benefits.

Despite all that, Republicans in Congress originally expressed opposition to giving states and localities a big dollop of aid. As we reported earlier, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) denigrated the idea of more money for state and local governments as “blue state bailouts,” citing the public pension policies of big states.

This analysis pleased the peanut gallery of right-wing ideologues ever eager to take potshots at public employees. But it’s wrong. The truth is that some of the biggest snouts in the federal trough have long been red states — including McConnell’s own home state of Kentucky, which gets $2.35 back from the federal government for every dollar it sends to Washington, the best return in the country.

McConnell has since made more moderate noises about federal aid, as well he should. “This isn’t partisan,” Jared Bernstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former chief economist to then-Vice President Joe Biden told me by email. Republican governors “are legitimately asking McConnell for help — but just what form and how much is to be seen.”

That will be the next battle. If the assistance is allocated by population, Baker notes, that will hurt blue states with large populations but more COVID-19 cases even as a share of their population.

“I’m sure the Republican intention is to fill much of the gap,” Baker said, but if Congress comes up with, say, only two-thirds of what’s needed, that will leave deficits in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

What’s really needed may be a multiyear program that assures state and local governments that help will still be available more than a year from now, when the impact of the pandemic is still likely to be felt.

But McConnell and Trump aren’t known as long-term thinkers or planners. “From a political view, probably the best thing is to get every cent you can now and hope that you get a Democrat in the White House and come back in January with some long-range plans,” Baker said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.