Column: Don’t be taken in by stem cell firms offering unsubstantiated therapies for COVID-19

“If you think this can help you,” Austin Wolff said earnestly into the camera, “it’s worth a shot.... It can only help.”

Wolff was speaking on a YouTube video produced for the Novus Center, a Studio City business run by his mother, Stephanie, selling stem cell-related products said to treat chronic pain, sexual performance issues and the effects of aging.

In recent weeks, Novus has begun directing its pitch at potential customers fearful about the effects of the novel coronavirus, implying that its “stem cell exosome vapor” — the supplies for which can be shipped overnight to customers’ homes — can improve lung strength and the immune system and “ward off viruses and disease.” (Exosomes are a form of cellular secretion.)

These are opportunistic businesses, and COVID-19 for them is an opportunity.

— Leigh Turner, University of Minnesota

Novus’ videos bristle with formal disclaimers. “It’s not going to cure anything,” Austin Wolff says on one video. “You should only do this if you want to try it.”

But the videos seem aimed at viewers desperate for any possible defense against a pandemic whose implacable spread seems to grow more frightening with every passing day.

Novus charges $10,000 for the shipment of vials containing the exosomes and nebulizing equipment. Stephanie Wolff says the business, which has been open for four years, has served about a dozen customers worried about COVID-19 in the last month or two.

Promoters of untested and unlicensed stem cell treatments have jumped into the coronavirus market with both feet, says Leigh Turner, a bioethicist at the University of Minnesota who has been tracking the spread of clinics pitching these treatments to consumers for years.

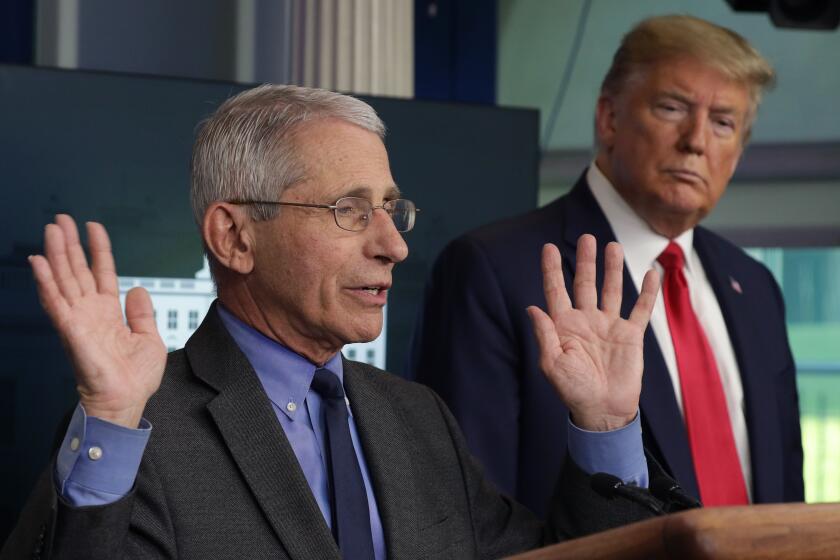

Now Trump is blaming the NIH for his coronavirus fiasco.

“The direct-to-consumer clinics have pivoted their marketing message to treating or preventing COVID-19,” Turner told me. “That’s not really shocking, in a way; these are opportunistic businesses, and COVID-19 for them is an opportunity.”

In a paper scheduled to be published shortly in the prestigious journal Cell Stem Cell, Turner examines how these businesses are “preying on public fears and anxieties” about the pandemic.

Typically, their claims fall short of actually promising cures or even specific treatments; that holds at bay the Food and Drug Administration, which has sought to shut down clinics offering unproven therapies for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and erectile dysfunction.

Some “use the language of ‘immune booster’ or ‘preventive intervention,’” Turner says. “They’re not trying to treat somebody who’s in an ICU bed. It’s more the worried well they’re going after — people who are anxious, fearful of the pandemic, and susceptible to claims that a stem cell procedure will reduce their chance of becoming infected.”

These treatments can come with a healthy price tag, ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars. But they run up against one indisputable fact: “There are no approved stem cell treatments for COVID-19.”

Those are the words of Martin F. Pera, a leading stem cell researcher who is editor in chief of Stem Cell Reports, the open-access journal of the International Society for Stem Cell Research. The society issued a stern warning March 6 against “claims that stem cells can be used to treat people infected with COVID-19.”

As for the products sold by Novus, the FDA warned consumers in December that “there are currently no FDA-approved exosome products.” The agency stated that “certain clinics across the country” offering such products to patients “deceive patients with unsubstantiated claims about the potential for these products to prevent, treat or cure various diseases or conditions.”

In what may be the harshest enforcement order yet against a clinic pitching unproven and potentially harmful stem cell “treatments,” a federal judge has ordered a Florida-based stem cell firm to cease offering the treatments or face thousands of dollars in fines.

We’ve reported for years on the proliferation of clinics selling purported therapies based on stem cell injections costing as much as $15,000 each.

These treatments aren’t supported by scientific research, typically aren’t covered by insurance, and have been targets of an FDA crackdown. (Turner did groundbreaking work with UC Davis biologist Paul Knoepfler in 2016, sounding the alarm about the spread of these clinics.)

In early April, the FDA sent letters to two stem cell firms, Dynamic Stem Cell Therapy of Henderson, Nev., and Kimera Labs of Miramar, Fla., that it said had been marketing their products for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19 and warning them that any such products would have to meet regulatory standards for drugs. But the agency didn’t explicitly threaten them with legal consequences. Kimera is the supplier of exosomes to Novus.

Frightened laypersons aren’t the only targets of claims for cellular treatments for COVID-19. So are decision makers and government regulators.

The FDA came under fire in March when it issued an “emergency use authorization” to allow the prescribing of two antimalarial drugs, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, for COVID-19 patients. The action came after President Trump had been relentlessly promoting the drugs as potential “game changers” in the battle against COVID-19.

Less than a month later, the FDA issued a warning against using the drugs against COVID-19 because of reports of serious heart problems in COVID-19 patients who had taken them, as well as the absence of evidence that they were safe and effective for treating the disease.

It wouldn’t be surprising to see more companies and clinics showing up in the media and on cable television hawking unsubstantiated stem cell treatments for COVID-19. On May 4, the San Diego stem cell firm Giostar issued a news release asserting that it had received “approval for a COVID-19 clinical trial...using stem cells to treat COVID-19 patients, under the approval of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ‘expanded access for compassionate use’ program.”

Is this plausible? We’ve reported before that Giostar had made untrue claims about its scientific connections: Several legitimate stem cell scientists the firm listed as members of its scientific advisory board said they had no connection with Giostar and had repeatedly asked that their names be removed from its website. The company has also acknowledged that it had exaggerated the professional credentials of its co-founder and chairman, Anand Srivastava.

Giostar’s claim in its news release that it would conduct the clinical trial under the FDA’s “expanded access for compassionate use” program is curious. That program, which allows doctors to prescribe unapproved drugs as a last resort for people suffering from life-threatening diseases with no established cure, covers patients for whom “enrollment in a clinical trial is not possible.”

One day last March, Kristin Comella took to the podium at a conference sponsored by the Academy of Regenerative Practices to talk about the marvels of stem cell-based therapies and the challenges facing its pioneers.

In other words, there doesn’t seem to be such a thing as a clinical trial conducted subject to the expanded access program.

Giostar didn’t respond to our request for comment. The FDA would say only that it “generally cannot disclose information about an unapproved application,” which certainly suggests that Giostar hasn’t won the approval it claims.

In the frenzied search for COVID-19 treatments, it may be difficult to distinguish promising efforts from those just grasping at the main chance.

“What we have right now is a COVID-19 gold rush,” Turner says. “Businesses are seeing this as a terrific opportunity” to get their applications for investigative new drug trials approved by the FDA — a process that can take years and generally requires the submission of extensive evidence from lab and animal studies.

Some companies are pitching drugs they’ve developed for non-viral diseases as possible COVID-19 treatments, a strategy that inspires some skepticism in the cellular medicine community.

“Anti-cancer therapies can take their effect over a period of weeks or months,” says Sean Morrison, a cancer expert at the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern

and chair of the public policy committee of the International Society for Stem Cell Research. The course of a viral disease unfolds over days, he observed.

“That’s such a different indication that it’s natural to be skeptical when a company that may have spent years developing something for an anti-cancer indication repurposes the same thing overnight as an anti-viral. Those are two completely different problems from an immunological point of view.”

The direct-to-consumer pitches by clinics reviewed in Turner’s paper typically “fuse pseudoscience, which is what they’re offering, with more credible forms of science.” He found numerous references in these pitches to research from China, often of doubtful scientific significance.

A Pennsylvania clinic offering stem cell treatment to “support lung health during COVID-19,” for example, cited a report from a Beijing hospital where seven patients who were injected with stem cells all “saw significant improvement in COVID-19 related pneumonia,” according to the clinic’s news release. It quoted its CEO stating, “This goes to support the wide range of healing and restoration that can be provided by [stem cell] therapy.”

After standing on the sidelines while a major public health crisis developed, the Food and Drug Administration finally has launched what could be a major crackdown on clinics hawking questionable and potentially dangerous stem cell therapies.

However, as Turner observes, the report didn’t specify the severity of the subjects’ pneumonia, the source of the stem cells, or results from a control group. “At best you can say that no one seemed to be harmed, but it’s hard to draw any firm conclusions about efficacy.”

The Novus Center hangs its pitch on what Stephanie Wolff describes as “a study that’s ongoing in China right now using exosomes ... to help with viral load, to help with inflammation of the lung, to help with pneumonia, to help with infection.”

The reference, however, is to a clinical trial in Wuhan that had not even begun to recruit test subjects at the time of its latest public report, which is dated Feb. 25. The researchers didn’t expect their trial to be completed until July 31.

As we’ve written before, the proliferation of stem cell clinics selling untested and unlicensed therapies has been a public health crisis for years. The COVID-19 pandemic will only deepen the crisis as clinics add the coronavirus to their menu of treatment claims.

Despite its crackdown campaign, the FDA has never taken strong enough action against this corner of the healthcare industry. It should act without delay to shut down opportunistic initiatives, or more innocent Americans will find their health, and their pocketbooks, at ever greater risk.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.